Traite de la Chymie. Enseignant par une brieve et facile methode toutes ses plus necessaires preparations.

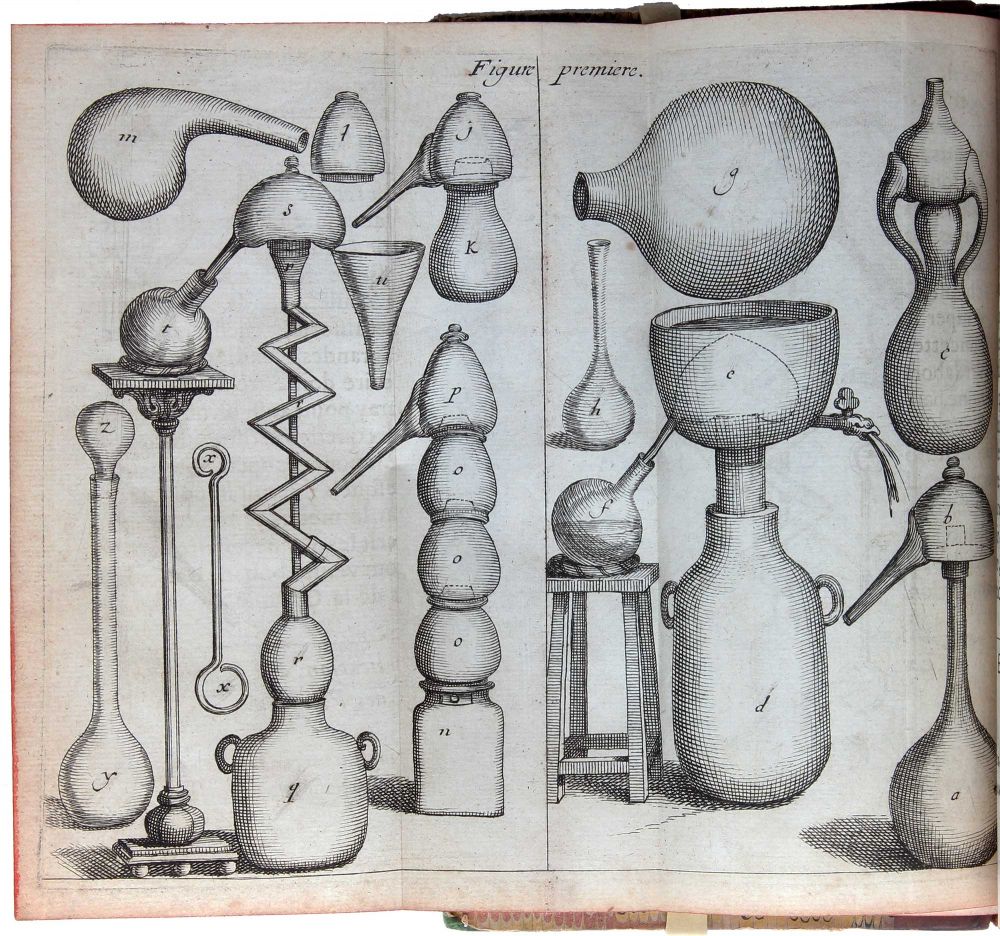

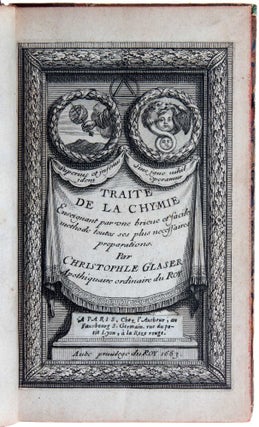

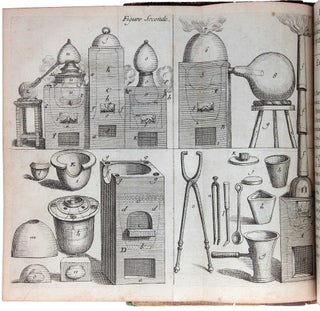

Paris: Chez l'autheur, 1663. First edition, rare, of this very important chemistry text, which went through some thirteen editions between 1663 and 1710. “The Traité is Glaser’s only publication. Printed in a small number at the author’s expense, the first edition was sold from his house. Rapidly becoming a best seller, many editions in French appeared, with translations into German and English. A milestone in the development of the chemical text, it is stripped of alchemical mysticism and gives clear descriptions of chemical preparations” (The Roy G. Neville Historical Chemical Library, p. 528). “The work is divided into two books: book I briefly describes the utility, definitions, principles, operations, and apparatus of chemistry: book II is devoted to a description of medicinal preparations drawn from the mineral, vegetable, and animal kingdoms. The section devoted to mineral remedies is by far the largest. Little is novel in these preparations, although Glaser displays individual refinements of technique. His recipe for a sel antifebrile (potassium sulfate made by heating saltpeter and sulfur and recrystallizing from water) became uniquely identified with him and was later known as sel polychrestum Glaseri. The naturally occurring mixed sulfate of sodium and potassium (3K2SO4:Na2SO4) was named glaserite in his honor. Due to his influence on Lemery, Glaser’s importance for the development of chemistry was greater than the contents of his book at first indicate. Although Fontenelle in his éloge of Lemery states that Lemery, finding Glaser obscure and secretive, abandoned studies with him after two months in 1666, the early editions of Lemery’s highly successful Cours de chymie bear a remarkable resemblance both in organization and content to Glaser’s textbook. There seems little doubt that Glaser’s modest work served as a model for at least the practical part of the most popular chemical textbook of the late seventeenth century” (DSB). No other copy listed on ABPC/RBH in the last 40 years. Christopher Glaser was born in 1615 in Basel, Switzerland. “Little is known about Glaser’s early life, but he seems to have been trained as a pharmacist in his native city, and references in his published work indicate that he traveled in eastern Europe to observe mining practice. Sometime prior to 1662 he settled in Paris, where he opened an apothecary’s shop in the Faubourg Saint-Germain. Here he prospered, becoming apothecary in ordinary to Louis XIV and to the king’s brother, the duke of Orleans. He also enjoyed the patronage of Nicolas Fouquet, the ill-fated superintendent of finances. In 1662 he was appointed demonstrator in chemistry at the Jardin du Roi in Paris in succession to Nicolas Le Fèvre. His most noted pupil in Paris was Nicolas Lemery. “The events of Glaser’s later life are likewise elusive. In 1672 he was implicated in the famous Brinvilliers poison case when evidence came to light that the marquise de Brinvilliers and her accomplice Gaudin de Sainte-Croix had used a recipe of Glaser’s to prepare the poison with which they disposed of the marquise’s father (1666) and two brothers (1669–1670). At this point Glaser disappeared from public life in France. If the preface by the printer to the 1673 edition of Glaser’s Traité is to be believed, Glaser died before completing the revisions for this new edition, which received the approbation of the Paris Faculty of Medicine on 15 October 1672. At her interrogation in 1676 the marquise de Brinvilliers alleged that Glaser had indeed prepared poison for Sainte-Croix but that he had been dead for a long time. One source maintains, however, that Glaser returned to Basel, where he died in 1678. “In the series of French chemical manuals of the seventeenth century, that of Glaser appeared between the more famous works of Le Fèvre and Lemery. Whereas Le Fèvre’s textbook drew on the Paracelsian-Helmontian tradition for its theoretical content and Lemery attempted a corpuscularian interpretation of the processes he described, Glaser largely eschewed theory and was content with a straightforward, concise recital of chemical operations and recipes” (DSB). The Traité “gives definitions of chemical operations in alphabetical order, from ‘alkooliser’ (powdering finely) to ‘vitrifier’, describes and illustrates vessels and furnaces and lutes, and the seven degrees of fire. The second book deals wiith preparations, minerals (including metals, coral and amber) occupying a large part of the whole. Vegetables take less space and the short section on animals deals with the distillation of human skull and blood, vipers, urine, wax, manna, honey, and May dew. In describing diaphoretic gold, made by burning linen rags soaked in a solution of gold in aqua regia mixed with saltpetre, Glaser says that a silver vessel rubbed with the moistened powder is gilded. He describes the casting of fused silver nitrate (pierre infernale, caustique perpetuel) in iron moulds; its corrosive effects are due to the nitric acid. He says 1 lb. of lead increases in weight by more than 2 oz. on calcination ‘à cause des corpuscules du feu qui s’incorporent avec luy’, and tin and other imperfect metals similarly increase in weight. “In his description of salts, Glaser mentions sel prunel made by throwing sulphur on fused saltpetre, and sel antifebrile (afterwards called sal polychrestum Glaseri, from [the Greek] ‘very useful’) by heating saltpetre and sulphur and crystallising the potassium sulphate from water. Oil of arsenic (arsenic trichloride) is made by distilling regulus of arsenic (the element) with corrosive sublimate, the residual mercury passing over at a higher temperature; magistery of bismuth (the oxynitrate) by pouring a solution of ‘bismuth ou estain de glace’ in nitric acid into water (before Lemery). He mentions ‘zinck’, which ‘approaches very close to the nature of bismuth but contains a purer sulphur’; although the metal was known to Le Fèvre and Glaser, they knew very little about it” (Partington, pp. 25-26).

Duveen 251; Edelstein 1000; Ferchl 186; Ferguson I, 321 (not in Young Collection); Neu 1637; Poggendorff I, 908. Partington, A History of Chemistry, vol. III, 1962. For a detailed account of the work, see: Neville, ‘Christophle Glaser and the ‘Traité de la Chymie’, 1663,’ Historical Studies in the Physical Sciences 10 (1979), pp. 25–52.

8vo (162 x 98 mm), pp. [ii, engraved title], [viii], 1-378, [3, privilege], with two folding engraved plates. Nineteenth century half-calf over marbled boards, richly gilt spine with red title label, edges died in red, corners in green vellum (joints starting but still strong and intact). A very good copy.

Item #3412

Price: $5,000.00