Four letters from Sir Isaac Newton to Doctor Bentley, containing some arguments in proof of a deity.

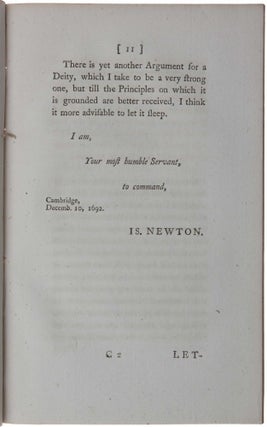

London: Printed for R. and J. Dodsley, 1756. First printing, very rare, of these letters of Newton which Koyré has described as “one of the most precious and important documents for the study and interpretation of Newtonian thought” (Koyré, Newtonian Studies (1965), p. 202). Newton here gives his views on the nature of gravity, on the formation of the solar system, on action-at-a-distance, and much else. He even foresaw in these letters the modern theory of galaxy formation (see below). Newton had been very careful to exclude such speculative ‘philosophical’ comments from Principia: in its second edition he famously proclaimed “Hypotheses non fingo,” or “I feign no hypotheses.” Bentley had been asked to deliver the inaugural series of Boyle Lectures, which “had to demonstrate, among other things, that the new science – that is to say, the ‘mechanical philosophy’ of which Boyle had been so firm an adherent, and the heliocentric astronomy – which had been assured a definitive victory over ancient view by Newton’s work, could not possible lead to materialism, but on the contrary offered a solid base for rejecting and confuting it … Bentley, a good theologian and an admirable philologist, was not prepared to deal with scientific questions. So, after having tried to acquaint himself with the difficulties and to surmount them by his own means, he decided to appeal to the master himself, and to ask whether or not the mathematical philosophy, and particularly Newtonian cosmology, could do without the intervention of a creative God or whether on the contrary they implied such intervention” (ibid.). “Richard Bentley follows so closely, and even so servilely, Newton’s teaching, or lessons—he copied nearly verbatim the letters he received from him, adding, of course, some references to the Scriptures and a good deal of rhetoric—that the views he expresses can be considered as representing, in a large measure, those of Newton himself” (Koyré, From the Closed World to the Infinite Universe (1957), p. 179). The four letters which Newton wrote in response to Bentley’s request were published as the present work. OCLC lists 5 copies, all in UK; there is also a copy at Harvard. No copy of these letters located in auction records in the last 75 years. “When the great English natural philosopher Robert Boyle died at the end of 1691, he endowed a lecture series designed to promote Christianity against what Boyle took to be the atheism that had infected English culture after the revolutionary period of the mid-century. Famous Newtonians such as Samuel Clarke and William Whiston would eventually give the Boyle lectures. The first “Boyle lecturer” was the theologian Richard Bentley (1662-1742), who would eventually become the Master of Newton’s alma mater, Trinity College, Cambridge... When preparing his lectures for publication—they had been presented to a public audience in London in 1692—Bentley conferred with Newton, hoping to solicit his help in deciphering enough of the Principia to use its results as a bulwark against atheism. Newton obliged, and a famous correspondence between the two began (eventually published as [the present work]). The exchange is of great philosophical interest, for Bentley elicited a number of important clarifications that have no peer within Newton's published oeuvre” (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy). Bentley’s first letter is lost, but from Newton’s reply we know that he must have “asked why some matter in the Universe formed the luminous Sun and other matter became the dark planets, whether the motions of the planets could arise from natural causes, whether the lower densities of the outer planets were caused by their distance from the Sun, and what produced the inclination of the Earth's axis… “In answering the first question, Newton made his famous prescient comments about the distribution of matter in the Universe: ‘As to your first query, it seems to me that if the matter of our sun and planets and all the matter in the universe were evenly scattered throughout all the heavens, and every particle had an innate gravity toward all the rest, and the whole space throughout which this matter was scattered was but finite; the matter on the outside of the space would, by its gravity, tend toward all the matter on the inside, and by consequence, fall down into the middle of the whole space and there compose one great spherical mass. But if the matter was evenly disposed throughout an infinite space, it could never convene into one mass; but some of it would convene into one mass and some into another, so as to make an infinite number of great masses, scattered at great distances from one to another throughout all that infinite space. And thus might the sun and fixt stars be formed, supposing the matter were of a lucid nature. But how the matter should divide itself into two sorts, and that part of it which is fit to compose a shining body should fall down into one mass and make a sun and the rest which is fit to compose an opaque body should coalesce, not into one great body, like the shining matter, but into many little ones; or if the sun at first were an opaque body like the planets, or the planets lucid bodies like the sun, how he alone would be changed into a shining body whilst all they continue opaque, or all they be changed into opaque ones whilst he remains unchanged, I do not think explicable by meer natural causes, but am forced to ascribe it to the counsel and contrivance of a voluntary agent.’ “Bentley wrote back questioning whether matter in a uniform distribution would convene into clusters because by symmetry there would be no net force, either on the central particle in a finite system or on all particles in an infinite system. And so, five weeks after his first letter, Newton replied in January 1693: ‘The reason why matter evenly scattered through a finite space would convene in the midst, you conceive the same with me; but that there should be a central particle so accurately placed in the middle as to be always equally attracted on all sides, and thereby continue without motion, seems to me a supposition as fully as hard as to make the sharpest needle stand upright on its point upon a looking-glass. For if the very mathematical center of the central particle be not accurately in the very mathematical center of the attractive power of the whole mass, the particle will not be attracted equally on both sides. And much harder it is to suppose all the particles in an infinite space should be so accurately poised one among another, as to stand still in a perfect equilibrium. For I reckon this as hard as to make, not one needle only, but an infinite number of them (so many as there are particles in an infinite space) stand accurately poised upon their points. Yet I grant it possible, at least by a divine power; and if they were once to be placed, I agree with you that they would continue in that posture without motion forever, unless put into new motion by the same power. When therefore I said, that matter evenly spread through all space, would convene by its gravity into one or more great masses, I understand it of matter not resting in an accurate poise … a mathematician will tell you, that if a body stood in equilibrio between any two equal and contrary attracting infinite forces; and if to either of these forces you add any new finite attracting force, that new force, how little soever, will destroy their equilibrium, and put the body into the same motion into which it would put it were those two contrary equal forces but finite, or even none at all; so that in this case the two equal infinities, by the addition of a finite to either of them, become unequal in our ways of reckoning; and after these ways we must reckon, if from the considerations of infinities we would always draw true conclusions.’ “Thus Newton recognized, qualitatively, the main ingredients of galaxy clustering (although he had the formation of the stars and solar system in mind): a grainy gravitational field produced by discrete objects, a multiplicity of cluster centers in an infinite (we would now say unbounded) universe, the impotence of the mean gravitational field in a symmetric distribution, and the finite force produced by perturbing an equilibrium state. Strangely, it would take nearly 300 years to quantify these insights and compare their results with the observed galaxy distribution” (NASA/IPACExtragalactic Database (NED)). “Newton’s correspondence with Bentley is justly famous for another reason. The criticisms of Newton's theory of gravity by Leibniz and Huygens would prove essential to the Continental reception of Newtonian natural philosophy more generally in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. Since Newton held both of these mathematicians in high regard… one might assume that their criticisms would have pressed Newton into articulating an extensive defense of the possibility of action at a distance. Newton presented no such defense; moreover, there is actually evidence that Newton himself rejected the possibility of action at a distance, despite the fact that the Principia allows it as a conceptual possibility, if not an empirical reality. The evidence lies in Newton's correspondence with Bentley. In February of 1693, after receiving three letters from Newton, Bentley wrote an extensive reply that attempted to characterize Newton's theory of gravity, and his understanding of the nature of matter, in a way that could be used to undermine various kinds of atheism. With the three earlier letters as his guide, Bentley makes the following estimation of Newton's understanding of the possibility that gravity could somehow be an essential feature of material bodies: ‘And as for gravitation, tis impossible that that should either be coæternal & essential to matter, or ever acquired by it. Not essential and coæternal to matter; for then even our system would have been eternal (if gravity could form it) against our atheist's supposition & what we have proved in our last. For let them assign any given time, that matter convened from a chaos into our system, they must affirm that before the given time matter gravitated eternally without convening, which is absurd. {Sir, I make account, that your courteous suggestion by your last, that a chaos is inconsistent with the hypothesis of innate gravity, is included in this paragraph of mine.} and again, tis unconceivable, that inanimate brute matter should (without a divine impression) operate upon & affect other matter without mutual contact: as it must, if gravitation be essential and inherent in it.’ “In reply to this letter, Newton refers back to this second proposition, making one of the most famous of all his pronouncements concerning the possibility of action at a distance: ‘The last clause of the second position I like very well. It is inconceivable that inanimate brute matter should, without the mediation of something else which is not material, operate upon and affect other matter without mutual contact, as it must be, if gravitation in the sense of Epicurus, be essential and inherent in it. And this is one reason why I desired you would not ascribe innate gravity to me. That gravity should be innate, inherent, and essential to matter, so that one body may act upon another at a distance through a vacuum, without the mediation of anything else, by and through which their action and force may be conveyed from one to another, is to me so great an absurdity that I believe no man who has in philosophical matters a competent faculty of thinking can ever fall into it. Gravity must be caused by an agent acting constantly according to certain laws; but whether this agent be material or immaterial, I have left open to the consideration of my readers” (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy).’ “Whether gravity acted through the mediation of a material ether or through the operation of an immaterial force, Newton was not prepared to say. The trouble was he was attracted to both views, and throughout his life could never take the decisive step of abandoning either” (Gjertsen, p. 219). According to Gjertsen (p. 217), the publication of the present work was due to the Bentley’s grandson Richard Cumberland (1732-1811). Cumberland went to Trinity College, Cambridge, aged 14, and took a degree in mathematics in 1750 as tenth wrangler. He served in various capacities as a civil servant, notably under Lord Halifax, but he is best remembered today as a dramatist, having penned some fifty-four plays (published and unpublished) in his lifetime.

8vo (206 x 130 mm), pp. [iv], 35, [1]. Disbound, preserved in a clamshell box. A fine copy.

Item #3537

Price: $8,500.00