An extraordinary collection of 69 publications by Herschel, bound for his son. They include offprints of his most important publications on photography, astronomy, mathematics, and electricity and magnetism, and light, many with authorial annotations, as well as the corrected page proofs of an article on the theory of probability which was read by James Clerk Maxwell and led him to lay the foundations of statistical mechanics.

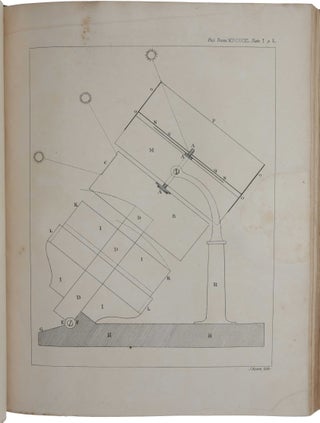

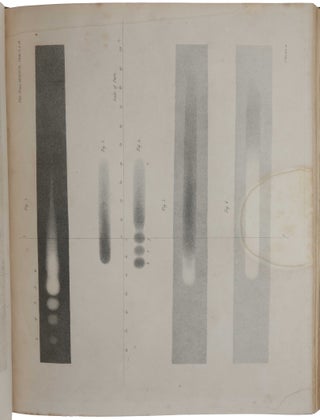

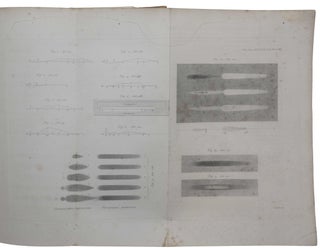

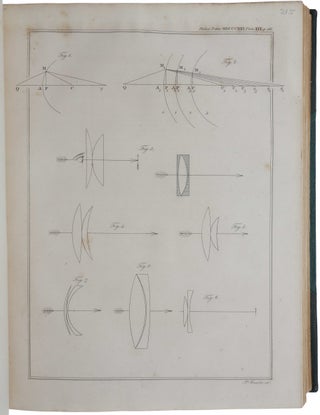

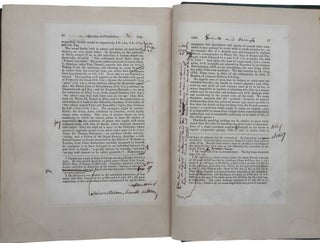

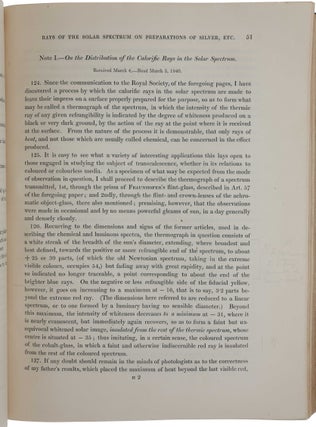

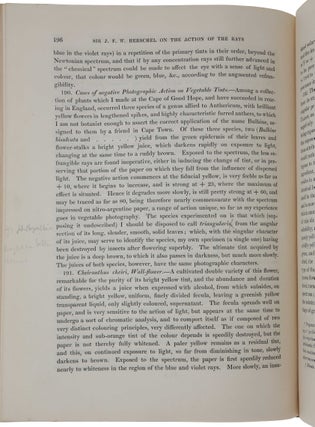

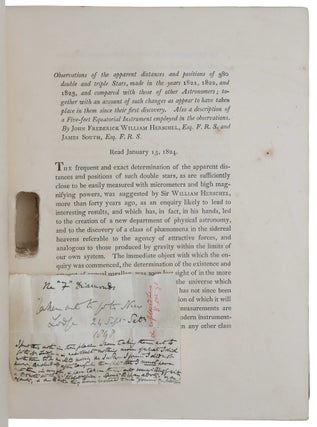

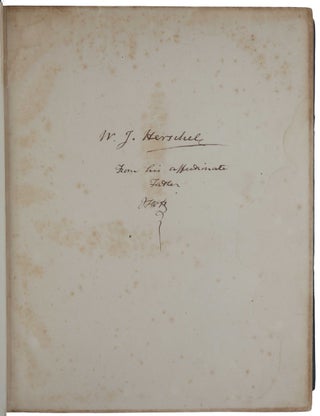

[1813-1850]. An extraordinary collection of works by Sir John Herschel (1792-1871), the outstanding astronomer and physical scientist of his day, assembled for presentation to his son William James Herschel (not to be confused with John’s father, the astronomer Frederick William). The collection includes offprints of Herschel’s three most important publications on photography, the first two of which have corrections and annotations in his hand. These offprints are of extreme rarity – ABPC/RBH list no other copy of any of them in the past 75 years. Herschel’s intensive investigations in photography and photochemistry during the late 1830s and early 1840s led to enormous advances: he coined the terms ‘positive’ and ‘negative,’ invented new photographic processes and improved existing ones, and experimented with colour reproduction. Among the mathematical works are several on the ‘calculus of operators’, as well as Herschel’s corrected galley proofs of a very important article on the theory of probability which was read by James Clerk Maxwell and led him to introduce probabilistic methods into the theory of gases, and thereby lay the foundations of statistical physics. There is also an offprint of a little studied paper in which Herschel describes a mechanical calculating machine, developed “In the course of a conversation with Mr. Babbage on the subject of applying machinery to the performance of numerical computations”. The astronomy papers include an offprint of Herschel’s great catalogue of 380 double stars (i.e., binary stars). All of the offprints are rare, with most either not listed on OCLC, or listed in only a handful of copies. “Herschel’s university years at St. John’s College, Cambridge, were devoted primarily to mathematics. Not only did he carry away the top academic prizes during this time, he was also elected a Fellow of the Royal Society, and co-founded the Analytical Society with Charles Babbage and George Peacock … Even at this early stage of his career, Herschel’s zeal to “leave the world wiser than [he] found it”, was already fully formed, and this clearly motivated his approach to photography when that too appeared on his horizon. His brief forays into legal studies and then into an academic career at Cambridge, ended abruptly at the close of 1816 when he settled finally on learning the trade of astronomer as his father’s assistant. Herschel’s life as a scientist of independent means, at a time when such a profession hardly existed, allowed him the freedom to pursue his personal interests, among them the study of light” (Hannavy, Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography, p. 653). Provenance: William James Herschel (inscription in John Herschel’s hand on front free endpaper of Vol. III: ‘W. J. Herschel // From his affectionate father // JFWH’); Dr. Sydney Ross, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (small red book label on each front paste-down). W. J. Herschel (1833-1917), the eldest son of John Herschel, is credited with being the first European to note the value of fingerprints for identification. Sydney Ross (1915-2013), leading chemist and bibliophile, was a former Professor of Colloid Science at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Troy, New York, and founder, and until his death, president of the James Clerk Maxwell Foundation. In 2001 he published a 590-page annotated Catalogue of the Herschel Library of William and John Herschel. In the following description of the works in these volumes, the numbers refer to the list of contents below. Photography (43, 44-47, 51, 59) “Photography was announced at the very height of Herschel’s career. He had just returned from four years in South Africa, having completed an examination of the skies of the Southern Hemisphere, and had reluctantly been raised to a baronetcy. Herschel learned of the announcement of the Daguerreotype on 22 January [1839], and of Talbot’s competing process within the space of a few days. By the 30th, needing no help from either inventor, he had made and fixed his own photographs on paper. Envisioning even the necessary steps to reverse the tones of the original, converting the negative image into a positive. “Herschel did not coin the name ‘photography’ … What Herschel did was to endorse this name and encourage its adoption within the scientific community. Herschel employed ‘photography’ in a paper titled ‘Note on the Art of Photography’ presented before the Royal Society on 14 March 1839, but he withdrew the paper from publication” (Hannavy, p. 654). “We have found proof that this action was taken out of consideration for Talbot, whose achievement Herschel did not wish to belittle by his own independent discovery … Herschel briefly referred to the matter in his next communication of 20 February 1840 (no. 43), in which after recapitulation of the contents of the previous paper, necessitated by its withdrawal, he says, ‘of course it will be understood that I have no intention here of interfering with Mr. Talbot's just and long antecedent claims’. This second communication, entitled ‘On the chemical action of the rays of the solar spectrum on preparations of silver and other substances, both metallic and non-metallic, and on some photographic processes abounds in important statements and observations which had a great bearing on the future of photography. Only the most significant can be enumerated here: “Although Herschel’s time was increasingly monopolized by the completion of his astronomical catalogues, he continued to follow up his photochemical experiments for the next three years … Early in 1842, the electro-chemist Alfred Smee sent Herschel a quantity of the bright red compound now called potassium ferricyanide. While testing the sensitivity of this substance under the light of the spectrum, Herschel noted that it acted with much the same sensitivity as guaiacum, and when thrown into water, it became a deep Prussian blue. Smee suggested two further compounds, Ammonio Citrate and Ammonio Tartrate of Iron, and by June of 1842, Herschel had developed both the Chrysotype, named for its use of gold “to bring about the dormant picture”, and the Cyanotype, his most practical and enduring process (no. 44). “Herschel’s 16 June 1842 paper presented his experiments not as independent inventions of processes. But as a series of observations on the basic principles of photographic chemical action. Although he describes his many experiments, both organic and metallic, he refrains from naming them or presenting wholly functional working processes. It would only be in November of 1842 that he would systematically describe the working details of his processes (no. 45). “Herschel’s experiments on photographic subjects came to a halt in 1843, victims of his astronomical writing and public duties. But his interest in photography never ceased … In 1845 Herschel published his final contribution to photographic research, an observation of what he called ‘epipolic dispersion’ (nos. 46 & 47). George Gabriel Stokes would later rename this phenomenon ‘fluorescence’, the study of which led directly to radiation photography of all types” (Hannavy, p. 655). Astronomy – double stars, nebulae and calculating machines (17, 19-25, 27-42, 48, 52-54, 57, 64, 66) “Though William Herschel is now remembered above all for his general surveys of nebulae and his star-counts, another field which he pioneered, and in which John was to make his mark, was the study of double stars. The appearance of pairs of stars close together was a noticeable feature of William’s sweeps, and led him to think that here, perhaps, was a means of determining stellar parallax and thus discovering the distances of the stars. Assuming that all stars were approximately of equal brightness … William argued that if one of the stars were dimmer than its companion, then it could be assumed to be much further away. The annual parallax of the brighter (and therefore nearer) star – that is, its apparent shift across the sky as the earth orbits the sun – could be detected by observing its varying separation from the more distant one (which would show negligible parallax) … “Though John Herschel’s first published astronomical paper was in 1822 and on a new method of calculating lunar eclipses, his first serious observational work was his measurement of double stars. This he did in cooperation with James South … it was a fruitful cooperation … for they were able to record details of no less than 380 double stars. These were catalogued systematically according to their right ascension (the celestial equivalent of terrestrial longitude), and in this represented an advance on the method adopted previously by William Herschel. Moreover, the colour and brightness of the component stars of each system was also given, as well as a comparison of the values for separation and position-angle which they had obtained with those of others. This excellent catalogue was published in the Philosophical Transactions in 1824 [no. 23]. This work also earned them the Lalande Prize of the Académie des Sciences in Paris for 1825, and in the next year, 1826, each received the Gold Medal of the Astronomical Society. “… in 1826 [John] produced three novel results. The first was his design for an ‘actinometer’ for measuring solar energy … The second was a monograph on the nebulae in Orion and Andromeda, as well as other observations made with his father’s ’20-foot’ telescope [no. 28]. John’s aim in re-examining the Orion nebula was to see whether any changes could be detected. “However, the most important of the three was a paper ‘On the parallax of the fixed stars’ [no. 20], which was published in the Philosophical Transactions. This contained a description of how the position-angle of a double star could possibly be used for determining annual parallax … such parallax was sought by his father using a micrometer to determine the change over time in relative separation between the stars. The angle to be determined was so small that it had remained undetected. What John Herschel now pointed out was that the orbital shift in space of the Earth would also give rise to a change in apparent position-angle … he gave annual parallaxes for some seventy stars; these ranged from 0.013 to 0.136 arc seconds which, if they did no more, at least indicated the extremely tiny angles that were involved [and hence the great distances of the stars] … “John’s preoccupation with double stars between 1825 and 1833 led him to develop a method for determining the orbits of those doubles which were in orbit around each other [no. 25]. It was an entirely graphical method based on Kepler’s laws of elliptical orbits. At this time it was significant work, for it applied physical considerations of gravity and techniques of computation out in the depths of space. For it he was awarded the Royal Medal of the Royal Society in 1833. When South moved to France, John had returned to Slough and his other work there included an examination of nebulae and star-clusters, resulting in the issue in 1833 of a list of 2307 objects [nos. 32 & 34]. This increased his father’s work by 525 new items, most of them very faint, and John’s catalogue gave their positions correct to 15 arc minutes in both right ascension and declination” (Ronan, pp. 43-7 in John Herschel 1792-1871: A Bicentennial Commemoration, 1992). The computations involved in his determination of the elliptic orbits of binary stars led him to devise a mechanical calculating machine for solving the equations, involving trigonometric functions, which arose (no. 26). The paper resulted from a conversation with Babbage, who was at the time building his Difference Engine. “Between 1834 and 1838 John Herschel and his family were in South Africa, John observing the southern skies as well as indulging in other of his scientific interests. In 1840, soon after his return, he caused some stir in astronomical circles by announcing that the very bright star Betelgeuse (α Orionis) underwent variations in brightness [no. 41]; it was in fact a long-period variable. Unfortunately he did not follow this significant observation by an onslaught on the subject of stellar variability which, in his paper, he referred to as “a highly interesting branch of Physical Astronomy” … “Innovative as ever, in 1841 he initiated a proposal for reform of the constellations [no. 42]. His concern was their ill-defined boundaries, and what he proposed, after discussions with his friends Francis Baily and William Whewell, was that these should be defined by quadrangles themselves specified by parallels to the celestial equator lying between agreed declinations. However, continental astronomers would not agree, and as international agreement was essential, John withdrew his scheme” (Ronan, p. 47). Mathematics – the calculus of operators, theory of probability (1-7, 49, 56, 69) Items 1-7 are concerned with Herschel’s work on the ‘calculus of operators’ and the ‘calculus of functions’, beginning with a contribution to the Memoirs of the Analytical Society. “A group of undergraduates, among whom were most notably George Peacock (1791-1858), Charles Babbage (1791-1871) and John Herschel (1792-1871), founded in 1812 the 'Analytical Society'. Its objective was to propagate the heresy of ‘pure d-ism against the Dot-age of the University’ [the former representing the Leibnizian approach to the calculus favoured on the Continent, the latter Newtonian fluxions still in use in Britain]. A project was set up to translate the second edition of Lacroix’s short treatise on the calculus (1802): the aim of the Analytical Society’s members was clearly that of changing the kind of education provided at Cambridge. However, the Analytical Society collapsed around 1814, having produced only a volume of Memoirs … Lacroix's treatise was intended for the students at Cambridge, as were the volumes of exercises on differential and integral calculus, functional equations and finite differences … After the collapse of the Analytical Society these works were published through the efforts of Babbage, Herschel and Peacock. After 1820 only Peacock remained at Cambridge … Herschel continued his father’s work on astronomy; Babbage was engaged in work on his difference and analytical engines … “Babbage, Herschel and Peacock were of great importance for the early nineteenth-century British calculus … [The] most important contribution from the Analytical Society’s members was that they initiated a trend of research which characterized much of British mathematics up to Cayley and Boole. The Memoirs of the Analytical Society were centred on the calculus of operators and on functional equations. “The calculus of operators dealt with the algebraical properties of the symbols of derivative and integral, and the related symbols of finite difference and summation. From this study it was possible to develop symbolic methods of integration of differential and difference equations … the application of the calculus of operators to the theory of integration originated mainly from Lagrange … Nevertheless, on the continent the Lagrangian school never played a prominent role. In Great Britain, on the contrary, the introduction of operational methods … launched a programme of research which continued up until the 1840s. “In addition, use of the calculus of functions started in Great Britain with the Analytical Society’s members, especially Babbage. The problem of recognizing the form of the arbitrary functions which occur in the integration of partial differential equations was the motivation for developing a theory of functional equations … The importance given to this theory is demonstrated by the inclusion in the Encyclopaedia Metropolitana of a lengthy essay on ‘functional equations’ by the young Augustus De Morgan (1836) … “The researches of the British Lagrangian school on the calculus of operators and the calculus of functions were the origin of important contributions to algebra and logic, such as Peacock's ‘pure algebra’, and De Morgan’s and Boole’s algebras of logic. But the predominance of the algebraical approach to the calculus had its own drawback: it did not allow many British mathematicians influenced by the Analytical Society to appreciate the importance of Cauchy’s rigorization of the calculus, which was motivated by the desire to avoid the ‘generalities of algebra’” (Guicciardini, The Development of Newtonian Calculus in Britain 1700-1800, pp. 135-8). Koppelman (‘The calculus of operations and the rise of abstract algebra,’ Archive for the History of Exact Sciences, Vol. 8 (1971), p. 156) has argued that the reason that the most important contributions of British mathematicians in the first half of the nineteenth century were to abstract algebra “was a direct response of the English to a specific aspect of the work of Continental analysts which became accessible to them. The subject came to be called, by the English, the calculus of operations.” Item 69, although ‘merely’ a review of a work by Adolphe Quetelet, is actually an important contribution to the theory of errors which had a crucial influence on James Clerk Maxwell. These are, in fact, Herschel’s corrected galley proofs, with copious manuscript annotations by Herschel. “The work of greatest influence on Maxwell’s development of gas theory may well be a review in the July 1850 Edinburgh Review of the magnificently titled collection of essays by Adolphe Quetelet, Letters Addressed to H.R.H. the Grand Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha on the Theory of Probabilities as Applied to the Moral and Political Sciences. The author of the review was Sir John Herschel. It ranged over many statistical questions, social and otherwise; a contemporary letter from Maxwell to his friend and future biographer, Lewis Campbell, strongly suggested that he had read it. The letter was undated and Campbell from memory put it as “June ? 1850.” But there can be little doubt that it was written just after the publication of Herschel’s review in July 1850. Maxwell discoursed on probability theory with remarks such as the following: “[T]he true Logic for this world is the Calculus of Probabilities…” Whether, indeed, Maxwell read the review in 1850, it was reprinted in Herschel’s Essays in 1857, and we know that Maxwell read and admired these essays” (Garber, Brush & Everitt (eds.), Maxwell on Molecules and Gases, p. 9). “More than two decades ago Charles Gillispie pointed out the similitude of the approaches to probability to be found in this review and in Maxwell’s paper [‘Illustrations of the dynamical theory of gases,’ 1860], and Stephen Brush subsequently recognized that the formal derivation of the error law given by Maxwell was in every important respect identical to the one introduced by Herschel in this essay” (Porter, The Rise of Statistical Thinking 1820-1900, p. 118). Physics – electricity, magnetism and optics (8-16, 18, 58, 63) “Like many active scientists in the early 19th century, Herschel was intent on discovering what light really was, and whether it moves in waves or in particles. Although no one in his generation, or indeed in the following generation, would formulate an answer to this question, Herschel believed that light travels in waves, that is, he believed in undulatory theory and not particle theory. He also believed, and would use photography to prove, that the visible part of the spectrum was a small portion of the actual spectrum. In 1819 Herschel began an exhaustive study of the nature of polarized light (nos. 9-12) … “The late 1820s were a busy time for Herschel, who was rapidly attaining a level of fame that would surpass his father’s. In 1827 he wrote his essay on Light (no. 13) for the Encyclopaedia Metropolitana. The essay … quickly attained the status of a classic and set out many of the principles on which he would conduct his photographic investigations” (Hannavy, p. 654). No. 8 is an important practical paper on the construction of telescope lenses, Herschel’s “His aim was a genuinely useful result, since previous attempts to derive conditions for an aplanatic achromatic doublet[i.e., one free of chromatic and spherical aberration] had yielded formulae too complex to be handled by a practical optician and had used data irrelevant to his methods and materials. Herschel’s analysis concluded with a set of tables, “set down for the convenience of those who may be inclined to make a trial of this construction,” of radii of curvature and focal lengths of the lenses of a compound object glass – an achromatic doublet that would be free from spherical aberration, both for celestial objects and for terrestrial objects situated on the axis of the telescope. The values could easily be adjusted for any focal length” (Bennet, ‘The first aplanatic object glass,’ Journal for the History of Astronomy 13 (1982), p. 206). No. 18 is the most interesting paper on electromagnetism in the collection, and also one of only two collaborative papers. “[François] Arago reported in 1824 an impressive new phenomenon which invited explanation. He arranged a disc made of copper – a non-magnetic – so that it could rotate in a horizontal plane, and above it he positioned a freely suspended magnet. When the disc was rotated, the magnet was first caused to move from its initial position, and it was subsequently dragged round by the disc. However, this force was not apparent when the disc was stationary. A year later Charles Babbage and John Herschel presented a paper to the Royal Society [no. 18] in which they varied the arrangement, for example, by rotating the copper disc between the poles of a powerful horseshoe magnet. They also determined the magnetic ‘susceptibility’ – their term to describe the observed effect – of different substances. Another important observation was that the magnetic effect produced by the disc was largely destroyed when it was punctured by radial slits. The observed phenomena were explained on the assumption that the interaction between, say, the rotating disc and the sympathetically moving magnet, was due to induction and, moreover, the particles comprising the magnet were affected by an inductive process. The other important point to notice about this paper is the authors’ insistence that the inductive process does not occur instantaneously but that ‘time enters as an essential element’” (Cantor, Michael Faraday, pp. 234-5). But the authors fell short of realizing that a totally new phenomenon need be postulated: the induction of eddy currents, and the discovery of electromagnetic induction had to wait another six years. Varia (50, 55, 60, 61, 62, 65, 67, 68) “In 1847, [Herschel] was asked by the First Lord of the Admiralty, Lord Auckland, to act as editor for a proposed “Manual of Scientific Inquiry” and to contribute an article on meteorology to it. The manual was intended to be a textbook for cadets at the Royal Naval College, Greenwich, and was to provide basic information on the scientific subjects that concerned naval officers. Articles on various aspects of astronomy, physics, and mathematics were contributed by Airy, Whewell, the geologist Adam Sedgewick, Sabine and Beaufort. A Manual of Scientific Enquiry was published in 1849. Herschel's article on “Meteorology” (no. 60) was reprinted in the eighth edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica and later published as a separate volume. A shortened and popularized version of it, entitled “On Weather and Weather Prophets,” was included in Herschel’s Familiar Lectures on Scientific Subjects” (Buttmann, The Shadow of the Telescope (1974), pp. 166-7). “His few hours of leisure Herschel devoted primarily to poetry – his own and translations. In 1842 he wrote a verse translation of Friedrich von Schiller’s “The Walk,” a poem he particularly liked because its evocations of nature reminded him of his own walks in the delightful countryside around Feldhausen [a farmhouse Herschel rented while he was observing in South Africa], which he often recalled with a certain degree of nostalgia” (ibid., pp. 171-2). CONTENTS Vol. I Vol. II Vol. III

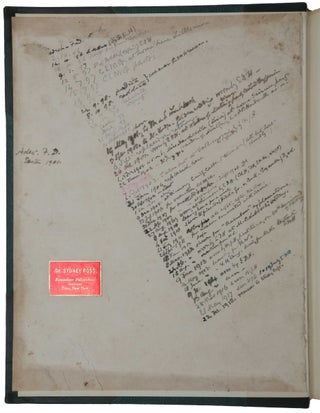

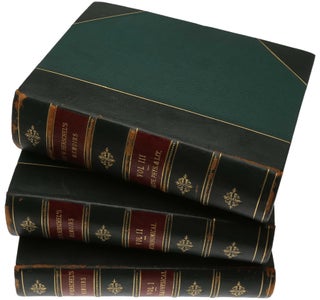

Three volumes, thick 4to (278 x 216). Contemporary dark green half-morocco, spines decorated in gilt and with two red lettering-pieces, covers ruled in gilt (slightly rubbed). A hole (4cm x 1.8cm) has been cut into the inner margin of pp. 1-402 of no. 23 (not affecting text or the title page). An inserted autograph note (probably in W. J. Herschel’s hand) indicates that seven diamonds were at one time secreted in this hole, and that they were lost, and then found, in the autumn of 1898 (sadly, the diamonds are no longer present). The inserted note reads: “The “7” Diamonds taken out to go to New Lodge, 24 September Saturday 1898 – and replaced 8 October 1898. I put this note in their place when taking them out to go to New Lodge – & recollect nothing more of what I did with them till on Monday morning as I woke – I found I did not know. Concluded after careful thought that I must have put them in my fob, and have taken them out unwittingly with a £5 note at the Railway ticket office – spent £44 on advert – & an agent – & on 8 Oct. they were restored to me ‘found on platform’.”.

Item #4321

Price: $85,000.00