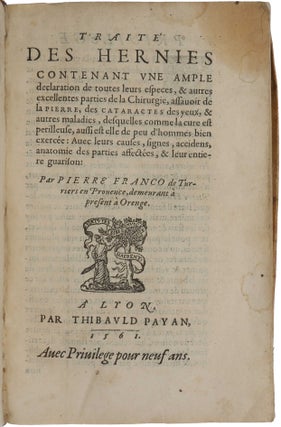

Traité des hernies: contenant une ample declaration de toutes leurs especes, & autres excellentes parties de la chirurgie, assavoir de la pierre, des cataractes, des yeux, & autres maladies, desquelles comme la cure est perilleuse, aussi est elle de peu dhommes bien exercée avec leurs causes, signes, accidens, anatomie des parties affectées, & leur entiere guarison …

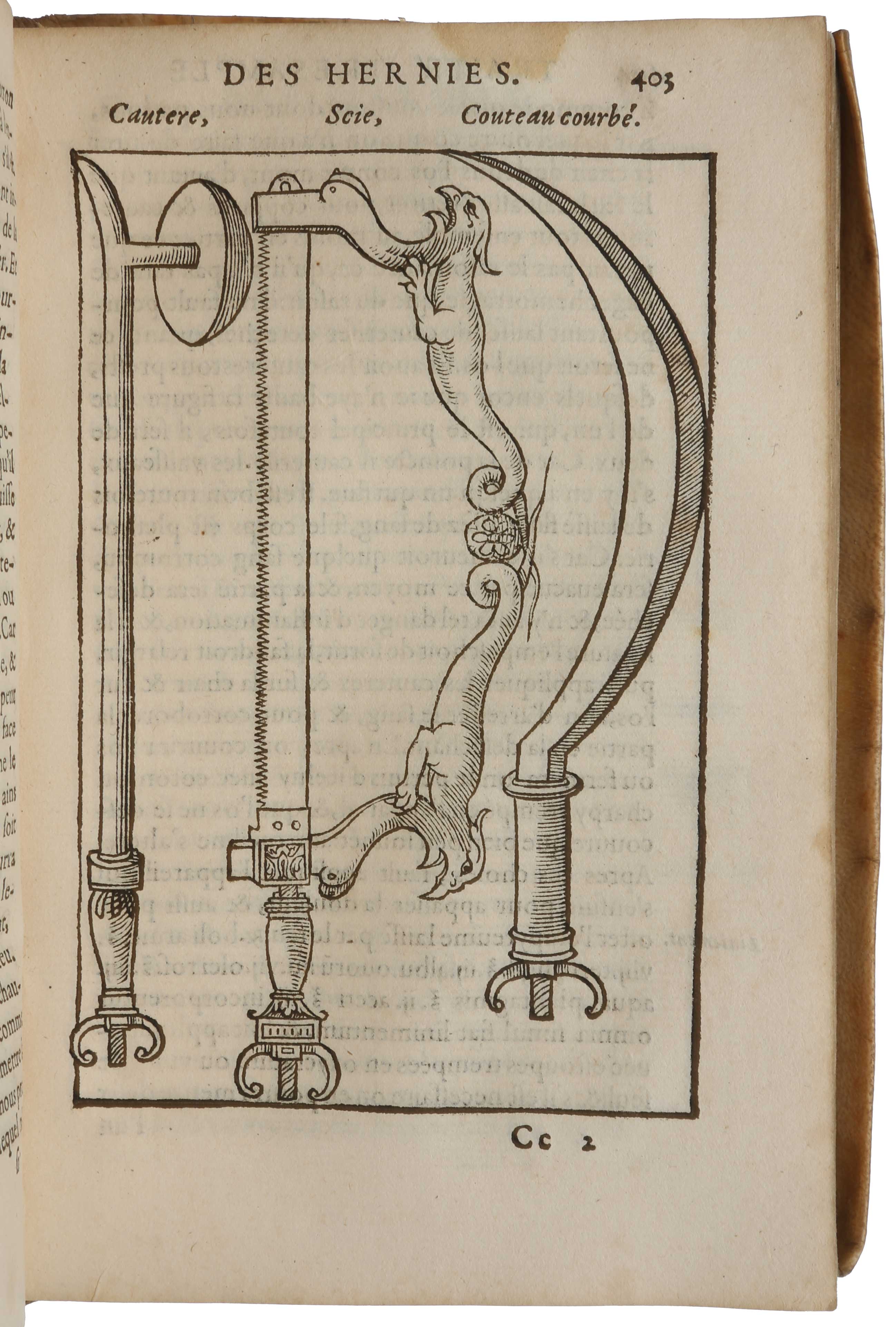

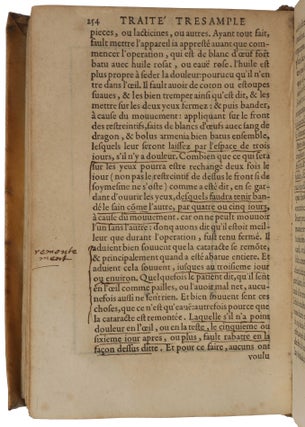

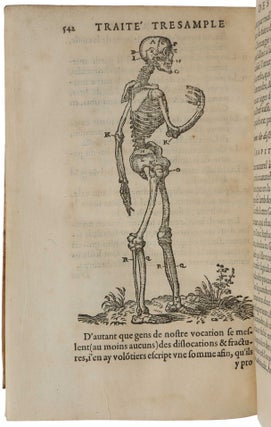

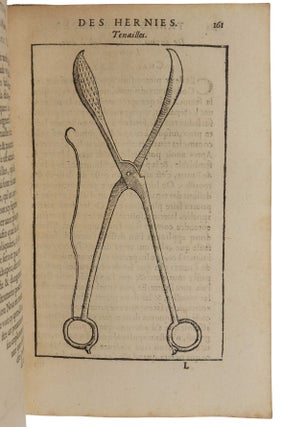

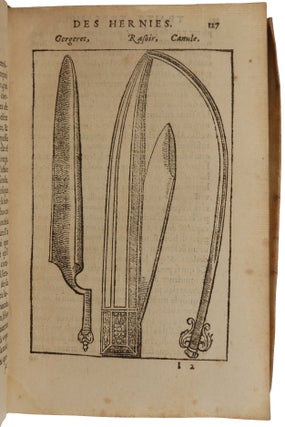

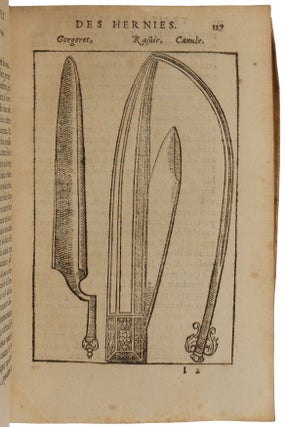

Lyon: Thibauld Payan, 1561. Second edition, almost four times the length of the first (1556), with 25 new illustrations including 22 instruments and three full skeletons. This is Franco’s major work, very rare, a copy in an untouched contemporary binding and with a fine provenance. “Pierre Franco, creator of suprapubic lithotomy cataract operation and surgical repair of hernia with preservation of the testis, is considered to be one of the greatest surgeons of the Renaissance and a forerunner of urology” (Androutsos, p. 255). “Franco was influential in bringing operative surgery back into the realm of regular surgical practice, recapturing it from the ignorant hands of charlatans and itinerant “cutters.” His major interest was in hernia surgery, to which he introduced several important innovations including an operation preserving the testicle (which was usually removed), a less risky incision at the base of the scrotum and methods for the surgical release of strangulated hernia. Franco was also the first surgeon to address himself seriously to the removal of bladder stones; he gave an account of perineal lithotomy and was the earliest to describe and perform the suprapubic incision” (Norman). Only two copies recorded on ABPC/RBH in the last 80 years. The only other copy we have located in commerce is in Ernst Weil’s catalogue 5 (ca. 1947), no. 93 (“of great rarity”, £100). OCLC lists copies in US at Chicago, Harvard, Indiana and West Virginia. “A less well known French-born contemporary of Paré, but one who well deserves our recognition as a shining star of Renaissance surgery, was Pierre Franco (?1500-1561). He was born in Provence of humble parents and had little schooling, but was early apprenticed to a barber-surgeon. As a Protestant, he was forced to flee from France and practiced his calling in Lausanne in Switzerland, although he eventually returned to Orange in France and his major work, Treatise on Hernias, was published in Lyon in 1561, just before his death. He deplored the fact that surgeons of his day rejected the use of open operations. This was because of the risks involved in such procedures, which they would often leave in the hands of charlatans. Franco was obviously a bold surgeon who carried out a wide range of the operative procedures known at that time. He describes in great detail his method of radical surgery for strangulated hernia, devising an incision at the base of the scrotum which he claimed was less dangerous than the higher incision. He also carried out cataract surgery and plastic operations on the face and described a new method for operating on cleft lip. In the surgery for bladder stone he was equally inventive … [he was] the first surgeon to remove a bladder stone successfully via an abdominal approach” (Ellis, p. 44). “'Considered especially from the point of view of the performance of operations,” wrote Nicaise, “Franco is the premier surgeon of the 16th century.” Hernial surgery constituted his principal field of interest. He describes, in minute detail, the technique of radical operation for inguinal hernia. Like all who preceded him (except for William of Salicet) after the time of Celsus, he removed the testicle as part of his usual procedure. However, for patients who had but one testis he devised an operation in which the organ was spared. Considering the usual incision at the level of the pubis to be unduly dangerous, he “invented” a low incision at the base of the scrotum which, he claims, was used in more than 200 persons by others and himself in the twelve or fifteen years since he first devised it. The clinical picture of strangulated hernia is clearly and vividly described, and methods for the surgical release of strangulation, both with and without opening the sac, are presented. Thus, for the first time, this life-saving procedure became part of the surgical armamentarium. “In the surgery for bladder stone he was equally enterprising and inventive. He described and pictured a number of instruments for catheterization and lithotomy, and pioneered in the introduction of several incisions, including the suprapubic approach. “Ophthalmic surgery and facial plastic operations also came within his scope, and he developed a new technique for certain forms of harelip. Whatever subject he dealt with was enriched and advanced through his ingenuity. It is with perfect justification that Nicaise said, “Where Franco appeared with all his genius, it was in operative therapeutics; it suffices for us to recall successively his operations to make evident the role that he has played, and to show that no surgeon has attached his name to so many lasting discovered” (Zimmerman & Veith, pp. 194-5). “The suprapubic approach to the bladder via a low mid-line abdominal incision, with the bladder distended to push away the peritoneum, is the usual open method employed in the removal of bladder stone today … The first recorded operation of this kind was carried out by Pierre Franco … In the year of his death he gave an account of an operation on a child of about three years of age who had a stone in the bladder the size of a hen’s egg. He was unable to remove the stone via the perineal approach because the enormous stone could not be pushed down into the neck of the bladder. The child’s parents begged him to try to relieve the small patient of his sufferings so he therefore pushed the stone up into the groin with his fingers in the rectum, got his assistant to fix the stone in this situation and then cut down immediately above the pubis into the calculus. The little patient recovered, but Franco advised others not to follow his example! … Indeed, it was not until the 18th century that Johann Bonnet was reported to have carried out the suprapubic operation frequently and with success at the Hôtel Dieu in Paris” (Ellis, p. 189). “Although not an academic, Franco decided to write a surgical text based on his many years of experience, which he modestly called a Petit Traité [Petit traité, contenant une des parties principales de chirurgie, laquelle les chirurgiens hernieres exercent, … Lyon, 1556] … His second book, Traité des hernies, was published in 1561 and includes chapters on anatomy, medicine and pharmacology. While in his first book Franco only cites Avicenna, Albucasis and Guy de Chauliac, Traité des hernies contains no less than 356 citations from a wide range of authorities, testifying to the remarkable learning of the supposedly unschooled author. Franco discusses the cleft lip in ample detail, devoting two chapters to the subject. He was the first to state the congenital nature of the malformation clearly, and referred to the unilateral harelip as the “lièvre fendu de nativité” (cleft lip present from birth). He provides a meticulous classification of various types of clefts, calling the bilateral harelip the “dent de lièvre” (hare’s tooth) presumably because this condition was frequently accompanied by a marked protrusion of the premaxilla bone with its teeth. “Franco gave a meticulous description of his surgical technique. He used dry sutures, pins and a triangular bandage. He emphasized that an accurate repair produced an unobtrusive scar, an outcome which was “particularly desirable when the patient was a girl”. “Surgery on the bilateral harelip was carried out in two stages due to the difficulty of closing an extremely wide cleft, often complicated by a protruding premaxilla. Franco recommended that the cheeks be mobilized in the repair, but did not hesitate to resect the premaxilla. As he wrote: “To extirpate this turpitude, we must first proceed in the manner described above, except when the teeth and maxillary segments are outside and cannot be covered by the mouth. There is no danger in cutting too much of that which serves no purpose, so one uses cutting forceps, or a saw or other instrument suitable for this, leaving the flesh which is over these teeth, if there is any, as it helps when sewing to the other parts on each side. And if there is such a distance between these lips that one cannot bring them together, it will be necessary to use dissection in the mouth similar to those on the preceding case, and proceed with the remainder of the closure as we have described” [Chapter XCVI]. This passage could not be more lucid and illustrates why Franco has been called The Father of Lip Repairs. Like Paré, he passed a pin or fibula across the repair and held this in place with a figure-of-eight thread, a technique invented by Henry de Mondeville (1260-1320) in 1306 for many wounds” (Santoni-Rugiu & Sykes, pp. 222-3). BM/STC French p.187; Garrison-Morton 3574; Waller 3223; Wellcome 2409 (imperfect); Norman 828 (modern binding, upper margin of title and final leaf repaired, $9200). Androutsos, ‘Pierre Franco (1505-1578): famous surgeon and lithotomist of the 16th century,’ Progress in Urology 14 (2004), 255-9; Ellis, A History of Surgery, 2002; Santoni-Rugiu & Sykes, A History of Plastic Surgery, 2007; Zimmerman & Veith, Great Ideas in the History of Surgery, 1993.

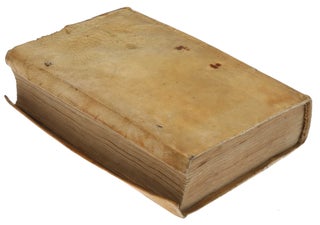

8vo (168 x 108 mm), pp. [16], 554, [2], with woodcuts in text showing a variety of surgical instruments for the procedures discussed and a series of three full skeletons at the end. Contemporary vellum, upper margin of rear board with some wear, remains of ties. A few leaves with light water stains. An entirely unrestored copy. Provenance: from the library of Jean Blondelet.

Item #4490

Price: $38,500.00