Sur l’Homme et le Développement de ses Facultés, ou Essai de Physique Sociale.

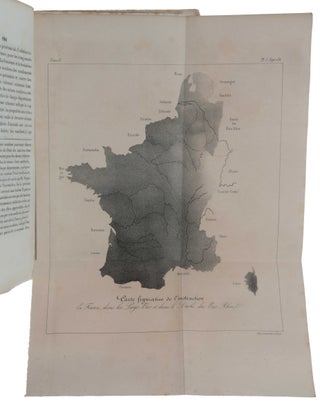

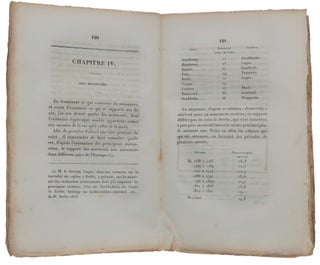

Paris: Bachelier, 1835. First edition of Quetelet's principal work in which he presented his conception of the homme moyen (“average man”) as the central value about which measurements of a human trait are grouped according to the normal distribution. “With Quetelet's work of 1835 a new era in statistics began. It presented a new technique of statistics, or, rather, the first technique at all. The material was thoughtfully elaborated, arranged according to certain pre-established principles, and made comparable. There were not very many statistical figures in the book, but each figure reported made sense. For every number, Quetelet tried to find the determining influences, its natural causes, and the perturbations caused by man. The work gave a description of the average man as both a static and dynamic phenomenon. This work was a tremendous achievement, but Quetelet had aimed at a much higher goal: social physics, as the subtitle of the work said; the same title under which, since 1825, Comte had taught what he later called sociology. Terms and analogies borrowed from mechanics played a great part in Quetelet’s theoretical explanation. To find the laws that govern the social body, one has to do what one does in physics: to observe a large number of cases and then take averages. Quetelet’s average man became a slogan in nineteenth-century discussions on social science” (DSB). “A rare, three-part review in the Athenaeum concluded by remarking: ‘We consider the appearance of these volumes as forming an epoch in the literary history of civilization’” (Stigler, p. 170). This work occasionally appears on the market, but we have not been able to locate any copy in original printed wrappers sold at auction. “It was in writings published in the 1830s that Quetelet (1796-1874) established the theoretical foundations of his work in moral statistics or, to use the modern term, sociology. First there was the idea that social phenomena in general are extremely regular and that the empirical regularities can be discovered through the application of statistical techniques. Furthermore, these regularities have causes: Quetelet considered his averages to be “of the order of physical facts,” thus establishing the link between physical laws and social laws. But rather than attach a theological interpretation to these regularities—as Sussmilch and others had done a century earlier, finding in them evidence of a divine order—Quetelet attributed them to social conditions at different times and in different places. This conclusion had two consequences: It gave rise to a large number of ethical problems, casting doubt on man’s free will and thus, for example, on individual responsibility for crime; and in practical terms it provided a basis for arguing that meliorative legislation can alter social conditions so as to lower crime rates or rates of suicide. “On the methodological side, two key principles were set forth very early in Quetelet’s work. The first states that ‘Causes are proportional to the effects produced by them’. This is easy to accept when it comes to man’s physical characteristics; it is the assumption that allows us to conclude, for example, that one man is ‘twice as strong’ as another (the cause) simply because we observe that he can lift an object that is twice as heavy (the effect). Quetelet proposed that a scientific study of man’s moral and intellectual qualities is possible only if this principle can be applied to them as well. The second key principle advanced by Quetelet is that large numbers are necessary in order to reach any reliable conclusions—an idea that can be traced to the influence of Laplace, Fourier, and Poisson … “Quetelet was greatly concerned that the methods he adopted for studying man in all his aspects be as ‘scientific’ as those used in any of the physical sciences. His solution to this problem was to develop a methodology that would allow full application of the theory of probabilities. For in striking contrast to his contemporary Auguste Comte, Quetelet believed that the use of mathematics is not only the sine qua non of any exact science but the measure of its worth … “The two memoirs which form the basis for all of Quetelet’s subsequent investigations of social phenomena appeared in 1831. By then he had decided that he wanted to isolate, from the general pool of statistical data, a special set dealing with human beings. He first published a memoir entitled Recherches sur la loi de la croissance de I’homme, which utilized a large number of measurements of people’s physical dimensions. A few months later he published statistics on crime, under the title Recherches sur le penchant au crime aux differens ages. While the emphasis in these publications is on what we would call the life cycle, both of them also include many multivariate tabulations, such as differences in the age-specific crime rates for men and women separately, for various countries, and for different social groups … In 1833 Quetelet published a third memoir giving developmental data on weight, Recherches sur le poids de Vhomme aux differens ages” (DSB). “Quetelet made two important advances toward the statistical analysis of social data: the first of these was formulating the concept of the average man, the second the fitting of distributions. Quetelet’s first awakening to the variety of relationships latent in society may have come with his investigation of population data, but his interests soon spread. From 1827 to 1835 he examined scores of potentially meaningful relationships through the compilation of tables and the preparation of graphical displays… He examined birth and death rates by month and city, by temperature, and by time of day. He calculated the month of conception from the birth month and tried to relate it to marriage statistics. He investigated mortality by age, by profession, by locality, by season, in prisons, and in hospitals. He considered other human attributes: height, weight, growth rate, and strength. Quetelet’s interests also extended to moral qualities: statistics on drunkenness, insanity, suicides, and crime. In 1835 he collected a number of earlier memoirs and added to them to form the two-volume book that was to gain him an international reputation as a social scientist: Sur l'homme et le developpement de ses facultes ou Essai de physique sociale. It was translated into English in 1842 as A Treatise on Man and the Development of his Faculties. “From 1819 Quetelet lectured at the Brussels Athenaeum, military college, and museum. In 1823 he went to Paris to study astronomy, meteorology, and the management of an astronomical observatory. While there he learned probability from Joseph Fourier and, conceivably, from Pierre-Simon Laplace. Quetelet founded (1828) and directed the Royal Observatory in Brussels, served as perpetual secretary of the Belgian Royal Academy (1834–74), and organized the first International Statistical Congress (1853). For the Dutch and Belgian governments, he collected and analyzed statistics on crime, mortality, and other subjects and devised improvements in census taking. He also developed methods for simultaneous observations of astronomical, meteorological, and geodetic phenomena from scattered points throughout Europe” (Britannica). Kress C.4017; DSB XI: 236-8; S. M. Stigler, The History of Statistics, 1986, Chapter 5.

“There was no mistaking Quetelet’s aim in this book: to lay the ground-work for social physics, to conduct a rigorous, quantified investigation of the laws of society that might some day stand with astronomers’ achievements of the previous century. His beginning was only tentative, and he was careful (sometimes to the point of being apologetic) not to claim more success than he could defend; but he was eloquent and his zeal caught the public eye” (Stigler, pp. 169-70).

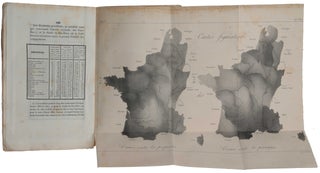

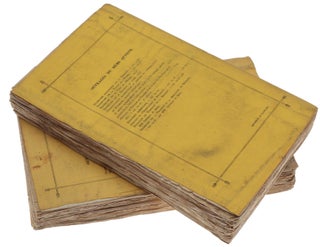

Two vols., 8vo (222 x 139 mm), pp. [4], xii, 327, [1], with two folding plates; [4], viii, 327, [1] , with four folding plates (four plates engraved, the other 2 lithographed). Original yellow printed wrappers, previous owner's signature stamp to front wrappers, small rectangular piece cut from the rear wrapper of vol. 2 (probably a price). Entirely unrestored in its original state. Some scattered relatively mild spotting (this work is usually found rather foxed). Very rare in such fine condition.

Item #4841

Price: $14,500.00