A Relation between Distance and Radial Velocity among Ex-tra-Galactic Nebulae. Offprint from: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Vol. 15, No. 3, March 1929.

Washington: National Academy of Sciences, 1929.

Extremely rare offprint issue of Hubble’s landmark paper which “made as great a change in man’s conception of the universe as the Copernican revolution 400 years before” (DSB). This paper “is generally regarded as marking the discovery of the expansion of the universe” (Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers). It established what would later become known as Hubble’s Law: that galaxies recede from us in all directions and more distant ones recede more rapidly in proportion to their distance. “…the repercussions were immense. The galaxies were not randomly dashing through the cosmos, but instead their speeds were mathematically related to their distances, and when scientists see such a relationship they search for a deeper significance. In this case, the significance was nothing less than the realization that at some point in history all the galaxies in the universe had been compacted into the same small region. This was the first observational evidence to hint at what we now call the Big Bang” (Simon Singh, Big Bang).

In the early 1920s, most astronomers believed that the universe was static and unchanging on the large scale. Einstein himself had introduced his ‘cosmological constant’ in 1917 to allow solutions of the equations of general relativity corresponding to a static universe. Two such solutions were found: Einstein’s matter-filled universe and Willem de Sitter’s empty universe. The latter model attracted much interest because it predicted redshifts for very distant objects, something which had been observed as early as 1912 by Vesto Slipher. However, De Sitter’s model was conceived by astronomers to be no less static than Einstein’s. In 1922 Alexander Friedmann developed a model of an evolutionary universe, which could be expanding, and this was re-discovered by Georges Lemaître in 1927. But Lemaître went further: he established theoretically the proportional relationship between the rate of expansion and distance. Important as these theoretical developments were, it was only observational data that could establish which of the models, if any, corresponded to the actual universe.

By the late 1920s, Edwin Powell Hubble (1889-1953) had established himself as the leading expert on extragalactic nebulae (now called ‘galaxies’). Trained at Yerkes Observatory, in 1919 Hubble had joined the staff of the Carnegie Institution’s Mount Wilson Observatory, the leading astrophysical observatory in the world, where he had access to the largest telescope in the world, the 100-inch Hooker reflector. With its aid, he had established in 1924 and 1925 that the spiral nebulae are external galaxies lying far beyond our own Milky Way galaxy, and that the observed universe is therefore much larger than our own galaxy.

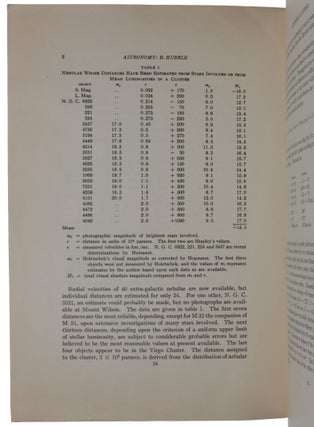

“By 1929 Hubble had obtained distances for eighteen isolated galaxies and for four members of the Virgo cluster. In that year he used this somewhat restricted body of data to make the most remarkable of all his discoveries and the one that made his name famous far beyond the ranks of professional astronomers. This was what is now known as Hubble’s law of proportionality of distance and radial velocity of galaxies.

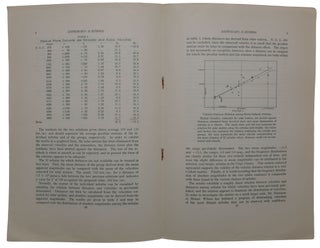

Since 1912, when V. M. Slipher at the Lowell Observatory had measured the radial velocity of a galaxy (M 31) for the time by observing the Doppler displacement of its spectral lines, velocities had been obtained of some forty-six galaxies, forty-one by Slipher himself. Attempts to correlate these velocities with other properties of the galaxies concerned, in particular their apparent diameters, had been made by Carl Wirtz, Lundmark, and others; but no definite, generally acceptable result had been obtained. In 1917 W. de Sitter had constructed, on the basis of Einstein’s cosmological equations, an ideal world-model (of vanishingly small average density) which predicted red shifts, indicative of recessional motion, in distant light sources; but no such systematic effect seemed to emerge from the empirical data. Hubble’s new approach to the problem, based on his determinations of distance, clarified an obscure situation. For distances out to about 6,000,000 light-years he obtained a good approximation to a straight line in the graphical plot of velocity against distance. Owing to the tendency of individual proper motions to mask the systematic effect in the case of the nearer galaxies, Hubble’s straight-line graph depended essentially on the data obtained from galaxies in the Virgo cluster. These indicated that over the observed range of distance, velocities increased at the rate of roughly 100 miles a second for every million light-years of distance.

“Einstein paid a special visit to Hubble at Mount Wilson in 1931 to thank him for his work, and said that introducing the cosmological constant in order to ensure a static universe had been ‘the greatest blunder of my life.’

“Hubble’s discovery stimulated much theoretical work in relativistic cosmology and aroused great interest in fundamental papers on expanding world models by A. Friedmann and G. Lemaître that had been written several years before but had attracted little attention. The interpretation of the straight line in Hubble’s graph of velocity against distance and of its slope were eagerly discussed. The constant ratio of velocity to distance is now usually denoted by the letter H and is called Hubble’s constant. It has the dimensions of an inverse time—its reciprocal, according to Hubble’s original determination, being approximately two (since revised to about ten) billion years. If the galaxies recede uniformly from each other, as was suggested by E. A. Milne in 1932, this could be interpreted as the age of the universe; but, whatever the true law of recessional motion may be, Hubble’s constant is generally regarded as a fundamental parameter in theoretical cosmology.

“Hubble’s work was characterized not only by his acuity as an observer but also by boldness of imagination and the ability to select the essential elements in an investigation. In his careful assessment of evidence he was no doubt influenced by his early legal training. He was universally respected by astronomers, and on his death N. U. Mayall expressed their feelings when he wrote: ‘It is tempting to think that Hubble may have been to the observable region of the universe what the Herschels were to the Milky Way and what Galileo was to the solar system’.” (DSB).

Parkinson, Breakthroughs, 508.

8vo (258 x 175 mm), pp. [1], 2-6, [7-8: blank] (first text leaf with some offsetting as often). Original printed wrappers. A fine and unmarked copy.

Item #5177

Price: $65,000.00