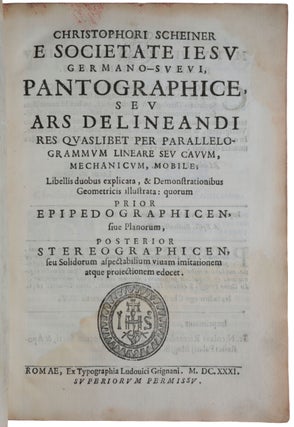

Pantographice, seu ars delineandi res quaslibet per parallelogrammum lineare seu cavum, mechanicum, mobile; libellis duobus explicata, & demonstrationibus geometricis illustrata: quorum prior epipedographicen, sive planorum, posterior stereographicen, seu solidorum aspectabilium vivam imitationem atque proiectionem edocet.

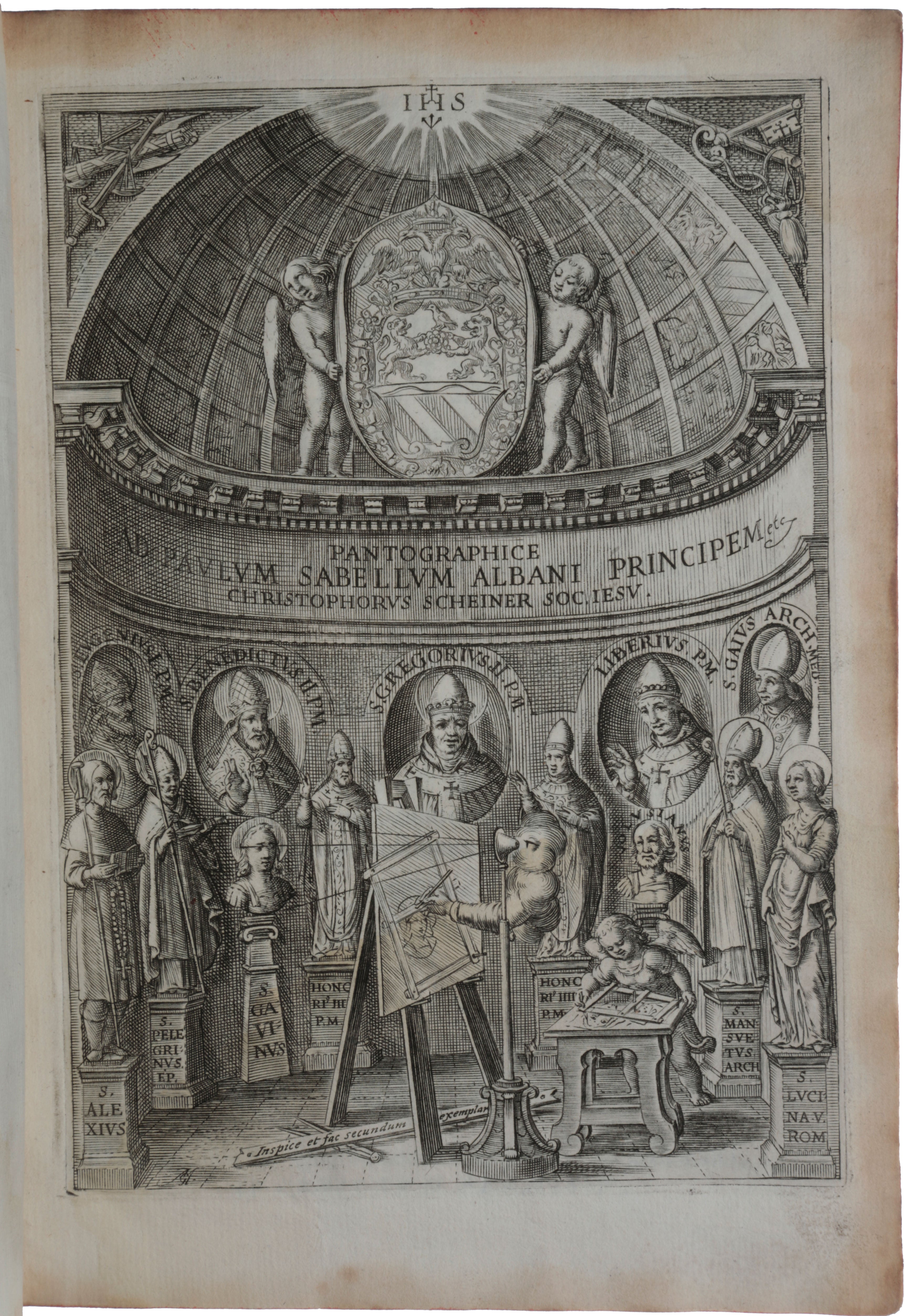

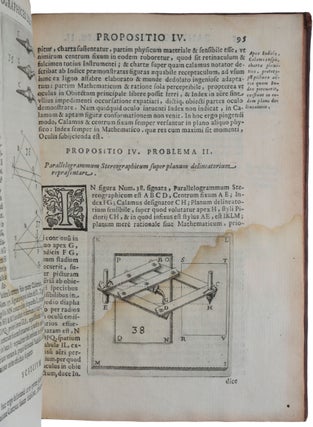

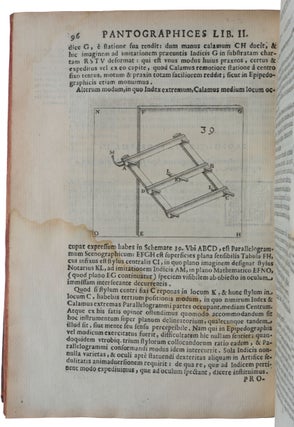

Rome: L. Grignani, 1631. First edition, rare, the Macclesfield copy, of the first description of the construction and use of the pantograph, a linkage mechanism that allows the duplication or scale-altering of a given diagram or drawing, which Scheiner invented about 1603. “This was probably the first copying device” (historyofinformation.com). In his Histoire des Mathématiques, Montucla wrote that “independently of his other writings, the invention of this instrument alone ought to have given immortality to his name” (Wallace, p. 420). Scheiner “was a major student of optics and an observational astronomer of real skill, who certainly possessed inventive powers on his own account, as was fully apparent in his devising of the pantograph. In the introduction to his Pantographice seu ars delineandi of 1631 he tells the story behind the invention of his drawing machine. In 1603 at Dillingen, a certain Master Gregorius, ‘an excellent painter’, boasted to Scheiner of his drawing device, but irritatingly refused to divulge its secrets. Tantalisingly, Gregorius said that ‘he did not believe that such a thing could even be imagined; in fact that it was not so much a human as a divine invention, which he thought had been brought and disclosed to him by no human efforts but by some celestial genius.’ All he would tell the astronomer was that it relied upon the use of compasses with a fixed centre. Intrigued by the possibilities, Scheiner set to work on his own account, and after a period of intense effort produced a device of great ingenuity and widespread utility – for copying or enlarging or reducing designs, for representing objects in perspective, and for the production of anamorphic designs. The secretive Gregorius was astonished to find his machine surpassed. The central idea behind Scheiner’s pantograph is the use of a parallelogram of levers for the proportional enlargement and diminution of a flat image. As such it provides the basis for the pantograph still available today. Mounted vertically it could also serve as a perspective machine. The frontispiece of the treatise shows it being used in this manner, and a further illustration [on p. 95] demonstrates its use with a special drawing board in which a window has been cut … the relative size of the image as transcribed by the draughtsman’s hand can be adjusted at will without altering the distance between the viewer’s eye and the intersection. The pantograph, as a device for making enlarged or reduced copies, became a standard instrument” (Kemp, p. 180). ABPC/RBH lists four other copies in the last 40 years, all in later bindings. Provenance: the Library of the Earls of Macclesfield (Sotheby’s, October 25, 2005, lot 1822, £1,320 = $2.329) (bookplate on front paste-down). “Scheiner attended the Jesuit Latin school at Augsburg and the Jesuit College at Landsberg before he joined the Society of Jesus in 1595. In 1600 he was sent to Ingolstadt, where he studied philosophy and, especially, mathematics under Johann Lanz. From 1603 to 1605 he spent his “magisterium”, or period of training as a teacher, at Dillingen, where he taught humanities in the Gymnasium and mathematics in the neighbouring academy. During this period he invented the pantograph, an instrument for copying plans on any scale; and his results were published several years later in the Pantographice, seu ars delineandi (1631)” (DSB). “In 1605 Scheiner returned to the Jesuit University of Ingolstadt. Here he continued to study the principles of the pantograph and to refine the device, and was also engaged in gnomonics. In the summer of 1605 his teacher Lanz wrote, ‘Master Scheiner in Dillingen recently wrote Father Ferdinand Crendel that he has discovered some new and easy method of describing sundials …’ Father Lanz depicted an ambitious young man who saw in his ability in mathematics and mechanical arts the road to advancement. The sundial and the pantograph did indeed cause Scheiner to be noticed among a wider circle within the Jesuit community, as well as by highly placed persons close to the order. In 1606 he was summoned to Munich by Duke William V of Bavaria, who had an avid interest in painting and was curious about Scheiner’s pantograph, and Scheiner spent some considerable time with the duke” (Reeves & Van Helden, p. 40). Scheiner’s mechanical interests and abilities led him to instruments, beginning with the pantograph and sundials, but increasingly after 1610 to telescopes. Scheiner was one of the first to observe sunspots by telescope, in March 1611, and in 1612 he published his findings anonymously. This led to a famous controversy with Galileo, who claimed to have observed sunspots earlier, involving the exchange of several letters. Galileo then turned to other matters, notably the preparation of the Dialogo, but Scheiner continued his observations of sunspots, culminating in the publication of his masterpiece, the Rosa ursine (1630). “Scheiner had come to Rome from Silesia in 1624 and what had been planned as a short trip dragged on until 1633 … in order to raise funds for his voyage back to Silesia, he turned to his old patron, the Archduke Leopold V of Habsburg. Leopold V referred Scheiner to Paolo Saveli (d. 1632), the Habsburg ambassador at the Holy See. Scheiner immediately set out to humour this new patron and dedicated his next publication, the Pantographice seu ars delineandi, to him. This little booklet describes the operation of a pantograph Scheiner had invented earlier. In the frontispiece he once more excels in the art of visual panegyrics. The image expertly combines a practical demonstration of his instrument with praise and glorification of the Savelli. Scheiner’s gallery of popes, bishops, and saints reaches back into antiquity and is closely connected to a fictive genealogy of the Savelli, as codified, for example, by Onofrio Panvinio (c. 1529-68) in his manuscript De gente Sabella of 1557 (which Scheiner used). The image stresses the Romanità of the Savelli and is perfectly in tune with the portrait gallery of popes whom the Savelli displayed as ancestors and family members in their Roman palace in the seventeenth century as insignia of their own nobility. “With the Pantographice seu ars delineandi and its frontispiece, Scheiner had created a gift that in two respects well befitted his patron Paolo Savelli. On the one hand, the description of the pantograph as a scientific and artistic instrument addressed the artistic sense of the Roman aristocrat and imperial ambassador, and the frontispiece reinforced this aspect. On the other hand, the genealogical design of the frontispiece was not only flattery, but also a gift that was highly à la mode among the status conscious in seventeenth-century Rome. Scheiner’s motive, just as in his dedication of the Rosa ursina to Paolo Giordano II, was gratefulness for and appreciation of benefits promised or received. The frontispieces to both the Rosa ursina and the Pantographice seu ars delineandi combine two key characteristics, namely, clear visual hints as to the contents of the books, i.e., the observation of sunspots and the operation of the pantograph, respectively, and the glorification of their associated patrons, Paolo Giordano II and Paolo Savelli. “In his letter of dedication to Savelli, Scheiner quoted two lines from Horace’s De arte poetica that originally referred to theatre: ‘Less vividly is the mind stirred by what finds entrance through the ears than by what is brought before the trusty eyes.’ Here Scheiner implicitly reveals his appreciation of the theatrical aspects of frontispieces. Appearance on stage was, so it seemed, more important than the printed word. And when it came to presenting oneself in the most suitable light and stressing one’s own relevance in order to establish bonds of patronage or court a potential Maecenas, the frontispiece turned out to be a perfect stage. A stage where ‘a small image teaches what many written words cannot say’” (Remmert, pp. 241-9). Scheiner’s pantograph is illustrated on p. 29 of Pantographice, seu ars delineandi. Wooden rods EF, EG, EH and GH are able to rotate at the hinges E, F, G, H where they are joined by means of metal screws; a point X on the rod EF is anchored in a fixed position. A stylus is inserted at a point O on the rod EH, and another at the point P on the rod FG. As O traces a plane figure, P traces a scaled image of the same figure. The proof given by Scheiner is an application of properties of similar triangles. By adjusting the length of the arms, or interchanging the roles of O and P, one can determine whether the copy is one-to-one, enlarged or reduced. “After inventing the drawing device, Scheiner started to teach how to use the pantograph in order to copy pictures in the plane not only as a professor to his students at the college, but also privately [p. 6]. However, he did not reveal the full power of the new device and only a few people were allowed to learn about the art of spatial drawing. Nevertheless, he had to admit [p. 7]: ‘However, I shall not deny that it might happen, that eventually one might find somewhere others, who tell things close to this. But I believe that nobody exists who is proceeding this way, with this method, and with this art. I am convinced that the art of spatial drawing by myself is completely new and came to the world as a first birth.’ “The monograph consists of two books describing both kinds of applications. The first book, ‘Pantographices libellus primus,’ describes ‘the art of drawing in the plane’: Given an arbitrary pre-image, it describes how to construct a similar image using the pantograph. The book is divided into two parts, the first being devoted to practical aspects only. In seven chapters, Scheiner reports about his invention, basic terms and definitions, materials and construction of the pantograph, tasks and assignments of different pieces and how to use the pantograph and with what effects. The second part deals with the theoretical background. Some aspects of the first part are taken up again and discussed from a theoretical point of view. In total fifteen ‘Propositiones’ and several ‘Lemmata’ are formulated and proved. In these proofs Scheiner’s way of reasoning follows the commonly used approach to such problems. Starting from a general lemma, the problem is presented with a concrete example and a claim is stated. What follows is a mathematically well thought-out proof. “In the second book, Pantographices libellus secundus,’ Scheiner continues his studies. Reflecting directly on the function and meaning of the pantograph, he focuses on several key aspects of his art of drawing. The book is divided into eight ‘Propositiones’, which are discussed in detail. For instance, he discusses the art of spatial drawing. He concludes that in this case the pre-image cannot stay connected to the stylus. In the subsequent chapters he describes the material, shape, and correct position of the stylus in spatial applications [p. 89ff]” (Clark et al., p. 328). Cicognara 658: “Quest'opera fu la prima che ci presentasse completo l'uso del Pantografo”; Brunet VI, 9188; DSB 12, 151 f.; Graesse VI/1, 298; Sommervogel VII, 739 no. 9; Vagnetti, EIIb22. Clark et al., Mathematics, Education and History, 2018. Kemp, The Science of Art, 1990. Reeves & Van Helden, On Sunspots, 2010. Remmert, ‘‘Docet parva picture, quod multae scripturae non dicunt.’ Frontispieces and their functions, and their audiences in seventeenth-century mathematical sciences,’ Chapter 9 in Transmitting knowledge: words, images, and instruments in early modern Europe (Kusukawa & Maclean, eds.), 2006. Wallace, ‘Account of the invention of the pantograph,’ Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 13 (1836), pp. 418-39.

4to (235 x 160mm), pp. [xii], 108, including half-title and additional engraved title, woodcut initials and head- and tail-pieces, engraved illustrations in text (some leaves slightly damp-stained). Contemporary English calf (rubbed, joints split but firm).

Item #5305

Price: $4,500.00