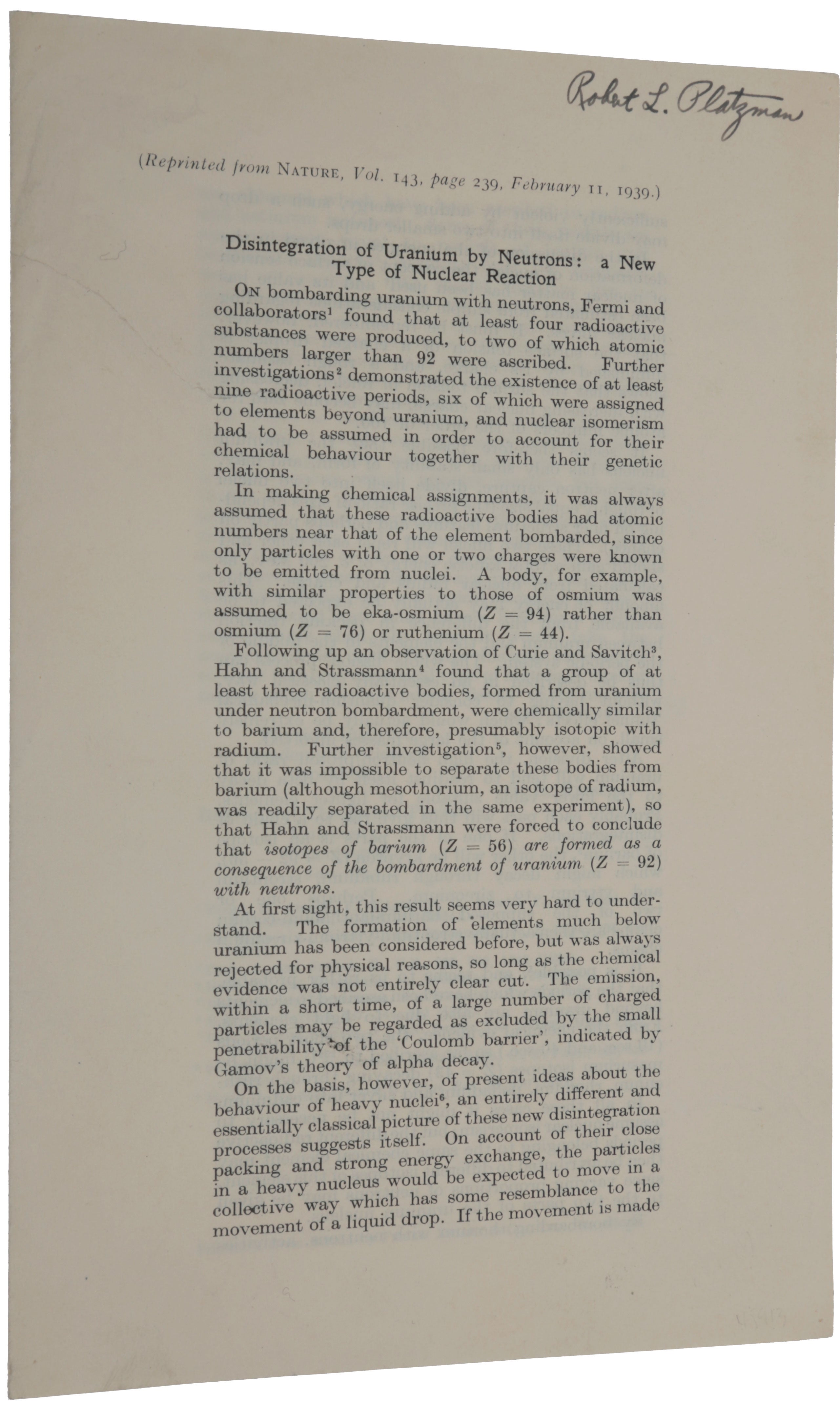

Disintegration of uranium by neutrons: a new type of nuclear reaction. Offprint from Nature, Vol. 143, No. 3615, 11 February 1939.

[London: Macmillan, 1939]. First edition, extremely rare offprint, of the discovery of nuclear fission, a process which had been observed by Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann the previous year but for which they were unable to provide an explanation. “In the late 1930s, a series of experiments showed that bombarding uranium with neutrons produced several new radioactive elements, which were assumed to have atomic numbers near to that of uranium (Z = 92). This assumption followed naturally from the prevailing view of nuclear decay, which involved the emission, through tunnelling, of only small charged particles (α and β). How then did one explain the formation of an element which was, as far as could be determined, identical to barium (Z = 56), and thus much smaller than uranium?” (Nature Physics Portal) “Experiments conducted in 1938 at Berlin by Hahn and Strassmann were reported to Lise Meitner, an Austrian scientist who had fled to Copenhagen to escape religious persecution. She and her nephew, O. R. Frisch, working in Niels Bohr’s laboratory, found the true explanation of these phenomena. The interpolation of a neutron into the nucleus of a uranium atom caused it to divide into two parts and to release energy amounting to about 200,000,000 electron volts. This process bore such a close similarity to the division of a living cell that Frisch suggested the use of the term ‘fission’ to describe it” (PMM). “When Frisch returned to Copenhagen with the news, Bohr immediately exclaimed ‘Oh, what idiots we have all been! Oh, but this is wonderful!’ Bohr publicised the discovery at a physics conference in the US later in January 1939, and soon others were confirming Hahn and Strassman’s results and Meitner and Frisch’s calculations. It was quickly recognised that fission of uranium’s 235 isotope would release further neutrons, possibly starting a chain reaction. On the eve of another war, the nuclear age had begun” (Sutton). The first nuclear reactor became operational in 1942 and the first atomic bomb was detonated in 1945. Hahn was the sole recipient of the 1944 Nobel Prize in Chemistry “for his discovery of the fission of heavy nuclei”. The official Nobel citation noted only that “Otto Hahn's long-time colleague, Lise Meitner, and her nephew, Otto Frisch, tackled the problem from a theoretical standpoint and proved that the uranium nucleus had been split”. No copy on OCLC. ABPC/RBH list a single copy (Sotheby’s, 16 November 2001, lot 126). Provenance: Robert Leroy Platzman (signature on title page). Platzman (1918-73) was a chemist at the University of Chicago Metallurgical Laboratory during World War II, the research group responsible for the first successful nuclear reactor in 1942. Its primary role was to design a viable method for plutonium production that could fuel a nuclear reaction. Platzman, together with 70 other scientists from Chicago, signed the letter sent on July 17, 1945 by Leo Szilard to urge President Truman not to use the atomic bomb against Japan. He was involved in establishing and publishing the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, a journal founded by Manhattan Project scientists who “could not remain aloof to the consequences of their work” (Atomic Heritage Foundation). “In December 1938, over Christmas vacation, physicists Lise Meitner (1878-1968) and Otto Frisch (1904-79) made a startling discovery that would immediately revolutionize nuclear physics and lead to the atomic bomb. Trying to explain a puzzling finding made by nuclear chemist Otto Hahn (1879-1968) in Berlin, Meitner and Frisch realized that something previously thought impossible was actually happening: that a uranium nucleus had split in two. “Lise Meitner was born in Vienna in 1878. She grew up in an intellectual family, and studied physics at the University of Vienna, receiving a doctorate in 1906. As a woman, the only position available to her at that time in Vienna was as a schoolteacher, so she went to Berlin in 1907 in search of research opportunities. Meitner was shy, but soon became a friend and collaborator of chemist Otto Hahn. In 1912 the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for chemistry was established, and she obtained a position there. During World War I Meitner volunteered as an x-ray nurse in the Austrian army. Upon returning to Berlin she was made head of a physics section at the KWI, where she did research in nuclear physics. “After the neutron was discovered 1932, scientists realized that it would make a good probe of the atomic nucleus. In 1934 Enrico Fermi (1901-54) bombarded uranium with neutrons, producing what he thought were the first elements heavier than uranium. Most scientists thought that hitting a large nucleus like uranium with a neutron could only induce small changes in the number of neutrons or protons. However, one chemist, Ida Noddack (1896-1978), pointed out that Fermi hadn’t ruled out the possibility that in his reactions, the uranium might actually have broken up into lighter elements, though she didn’t propose any theoretical basis for how that could happen. Her paper was largely ignored, and no one, not even Noddack herself, followed up on the idea. “Following Fermi’s work, Meitner and Hahn, along with chemist Fritz Strassmann (1902-80), also began bombarding uranium and other elements with neutrons and identifying the series of decay products. Hahn carried out the careful chemical analysis; Meitner, the physicist, explained the nuclear processes involved. “Meitner, who had Jewish ancestry, worked at the KWI until July 1938, when she was forced to flee from the Nazis. Her research was her whole life, and she had tried to hang on to her position as long as possible, but when it became clear that she would be in danger, she left hastily, with just two small suitcases. She took a position in Stockholm at the Nobel Institute for Physics, but she had few resources for her research there, and felt unwelcome and isolated. She kept up her correspondence with Hahn, and continued to advise him about their joint research. “In December 1938, Hahn and Strassmann, continuing their experiments bombarding uranium with neutrons, found what appeared to be isotopes of barium among the decay products. They couldn’t explain it, since it was thought that a tiny neutron couldn't possibly cause the nucleus to crack in two to produce much lighter elements. Hahn sent a letter to Meitner describing the puzzling finding. “Over the Christmas holiday, Meitner had a visit from her nephew, Otto Frisch, a physicist who worked in Copenhagen at Niels Bohr’s institute. Meitner shared Hahn’s letter with Frisch. They knew that Hahn was a good chemist and had not made a mistake, but the results didn’t make sense. They went for a walk in the snow to talk about the matter, Frisch on skis, Meitner keeping up on foot. They stopped at a tree stump to do some calculations. Meitner suggested they view the nucleus like a liquid drop, following a model that had been proposed earlier by the Russian physicist George Gamow and then further promoted by Bohr. Frisch, who was better at visualizing things, drew diagrams showing how after being hit with a neutron, the uranium nucleus might, like a water drop, become elongated, then start to pinch in the middle, and finally split into two drops. “After the split, the two drops would be driven apart by their mutual electric repulsion at high energy, about 200 MeV, Frisch and Meitner figured. Where would the energy come from? Meitner determined that the two daughter nuclei together would be less massive than the original uranium nucleus by about one-fifth the mass of a proton, which, when plugged into Einstein’s famous formula, E=mc2, works out to 200 MeV. Everything fit. “Frisch left Sweden after Christmas dinner. Having made the initial breakthrough, he and Meitner collaborated by long-distance telephone. Frisch talked briefly with Bohr, who then carried the news of the discovery of fission to America, where it met with immediate interest. “Meitner and Frisch sent their paper to Nature in January. Frisch named the new nuclear process “fission” after learning that the term “binary fission” was used by biologists to describe cell division. Hahn and Strassmann published their finding separately, and did not acknowledge Meitner’s role in the discovery … “Scientists quickly recognized that if the fission reaction also emitted enough secondary neutrons, a chain reaction could potentially occur, releasing enormous amounts of energy. Many scientists joined the efforts to produce an atomic bomb, but Meitner wanted no part of that work, and was later greatly saddened by the fact that her discovery had led to such destructive weapons. She did continue her research on nuclear reactions, and contributed to the construction of Sweden's first nuclear reactor. Hahn won the Nobel Prize in chemistry in 1944, but Meitner was never recognized for her important role in the discovery of fission” (American Physical Society, www.aps.org/publications/apsnews/200712/physicshistory.cfm). Meitner was crucial, not only to the explanation of Hahn and Strassmann’s experimental findings, but to the findings themselves. “In the fall of 1938, Meitner and other physicists were highly skeptical of Hahn and Strassmann’s finding that the slow neutron irradiation of uranium produced radium … It was she who urgently requested that Hahn and Strassmann test their radium more thoroughly, which led directly to the barium finding. She also was the one who immediately assured Hahn that a disintegration of the uranium nucleus was possible, after which he added to the proofs of the barium publication the suggestion that uranium might have split in two.Had Meitner been in Berlin at the time, the discovery of fission would, without question, have been understood as the superb achievement of an interdisciplinary team. Instead, Meitner was in exile, and she and physics were largely written out of the history of the discovery. The barium finding was published under the names of Hahn and Strassmann only—not because Meitner failed to provide an explanation but because it would have been politically impossible for Hahn and Strassmann to include her, a Jew in exile, as a coauthor. The records also show that Hahn quickly sought political cover and distanced himself from Meitner, claiming that the discovery was due to chemistry alone and that physics had delayed and impeded it, a view that was eventually codified by the Nobel Prize decisions. What kept Meitner from being completely obscured was that her theoretical interpretation with Otto Frisch was recognized as a brilliant extension of existing nuclear theory to the fission process. But the separate publications created an artificial divide—between chemistry and physics, experiment and theory, discovery and interpretation. It is important to recognize that this divide and Meitner’s exclusion from the fission discovery do not reflect how the science was done but are instead artifacts of her forced emigration and the political conditions in Nazi Germany at the time” (Sime). News of the discovery of fission spread rapidly. Meitner and Frisch communicated their results to Niels Bohr, who was in Copenhagen preparing to depart for the United States via Sweden and England. Bohr confirmed the validity of the findings while sailing to New York City, arriving on January 16, 1939. Ten days later Bohr, accompanied by Enrico Fermi, communicated the latest developments to some European émigré scientists who had preceded him to the United States and to members of the American scientific community at the opening session of a conference on theoretical physics in Washington, D.C. As with many other Nature offprints, such as the famous three-paper DNA offprint of 1953, this offprint was printed from the same type as the journal printing but in a single column, while the journal printing was made in double columns. Norman 1487 (journal issue); PMM 422b. Sime, ‘Lise Meitner and the discovery of fission,’ Physics Today 68 (2015), p. 10. Sutton, ‘Hahn, Meitner and the discovery of nuclear fission’ (https://www.chemistryworld.com/features/hahn-meitner-and-the-discovery-of-nuclear-fission/3009604.article).

8vo (210 x 137 mm), pp. [3]. Single sheet, folded once (closed tear to upper inner margin, just entering text but without loss).

Item #5323

Price: $18,000.00