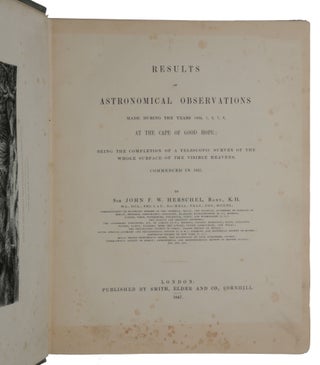

Results of astronomical observations made during the years 1834, 5, 6, 7, 8, at the Cape of Good Hope; being a completion of a telescopic survey of the whole surface of the visible heavens, commenced in 1825.

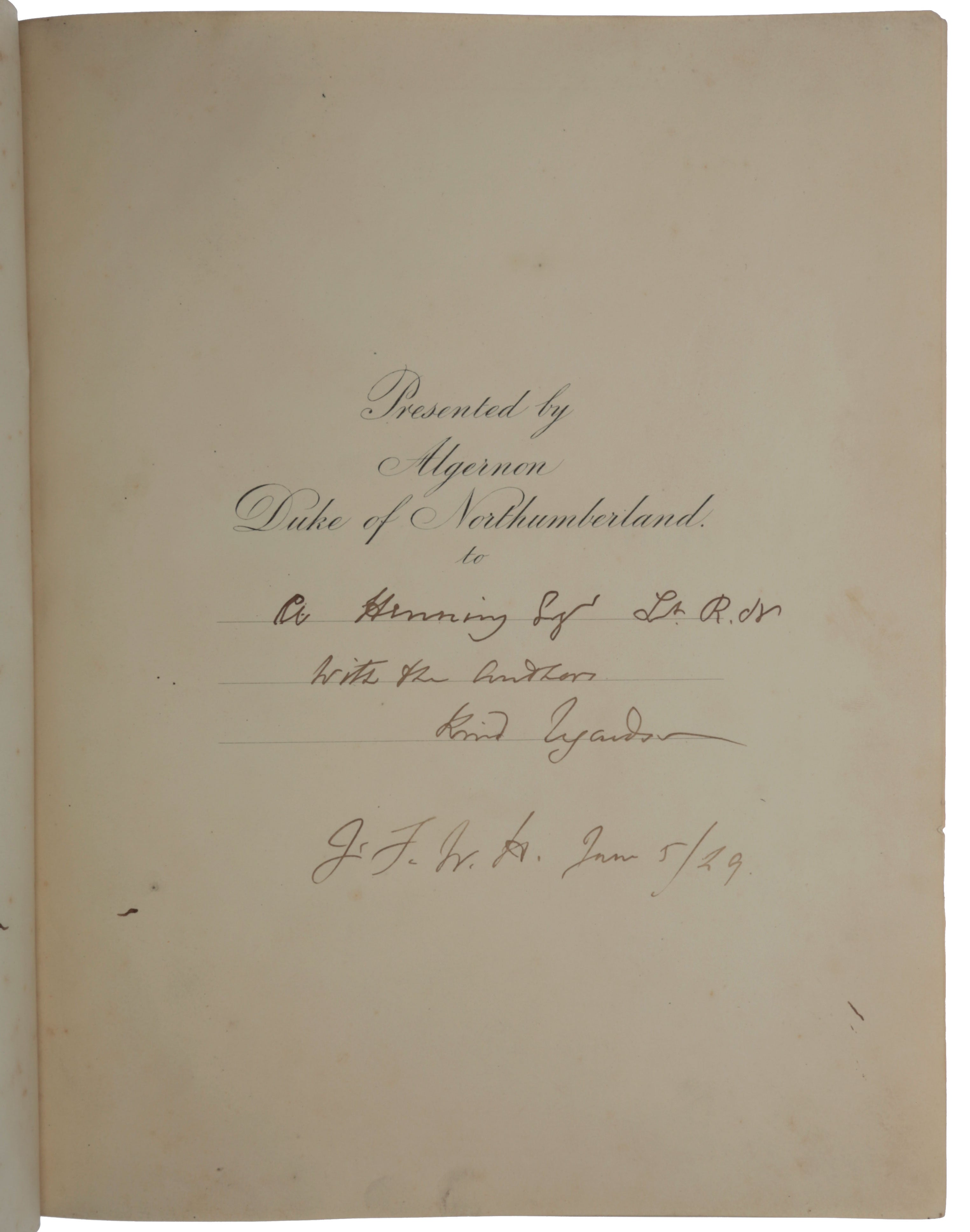

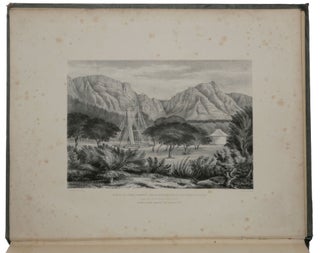

London: Smith, Elder & Co., 1847. First edition, inscribed presentation copy, of Herschel’s greatest astronomical work, inscribed to the Captain of the ship that brought Herschel and his family back from South Africa. This is a monumental survey of the stars of the southern hemisphere, a complement to his father’s survey of the northern celestial hemisphere. Herschel devoted five years to the project, which he chose to carry out at the Cape of Good Hope. In a suburb south of Cape Town he constructed a 20-foot reflecting telescope, with which he methodically explored the night skies. “By 1838 he had swept the whole of the southern sky, catalogued 1,707 nebulae and clusters, and listed 2,102 pairs of binary stars. He carried out star counts, on William Herschel’s plan, of 68,948 stars in 3,000 sky areas … He produced detailed sketches and maps of several objects, including the Orion region, the Eta Carinae nebula, and the Magellanic Clouds, and extremely accurate drawings of many extragalactic and planetary nebulae … Herschel invented a device called an astrometer, which enabled him to compare the brightness of stars with an image of the full moon of which he could control the apparent brightness, and thus introduced numerical measurements into stellar photometry” (DSB). “Herschel stands almost alone in his attempt to grapple with the dynamical problems presented by star-clusters, and his analysis of the Magellanic Clouds was decisive as to the status of nebulae” (ODNB). “By the end of 1842 [Herschel] had performed without assistance the computations necessary for the publication [in this work] of his Cape observations. In September 1843 the letterpress was ‘fairly begun,’ and after some delays the work appeared in 1847, at the cost of the Duke of Northumberland, in a large quarto volume, entitled ‘Results of Astronomical Observations made during the years 1834–8 at the Cape of Good Hope.’ Besides the catalogues of nebulae and double stars, it included profound discussions of various astronomical topics, and was enriched with over sixty exquisite engravings. He insisted in it upon the connection of sun-spots with the Sun’s rotation, and started the ‘cyclonic theory’ of their origin. [Herschel] investigated graphically the distribution of nebulae, but fluctuated in his views as to their nature. Regarding them in 1825 as probably composed of ‘a self-luminous or phosphorescent substance, gradually subsiding into stars and sidereal systems” (Memoirs of the Royal Astronomical Society, vol. 2, p. 487), he ascribed to them later a stellar constitution, and finally inclined to suppose them formed of ‘discrete luminous bodies floating in a non-luminous medium’” (ODNB). ABPC/RBH list only three presentation copies. Provenance: Additional lithograph presentation leaf inserted before the half-title reading “Presented by Algernon Duke of Northumberland to” and completed in ink by Herschel as follows: “A. Henning Esqr. Lt. R.N. / With the Authors / Kind regards / J. F. H. June 5/49.” “Herschel’s first astronomical paper, on the computation of lunar occultations (1822), was published when he was already working in London on systematic observations of double stars with James South, the possessor of two excellent refracting telescopes. It had once been thought that a close pair of stars of differing magnitudes must result from the accidental near alignment of two similar stars at vastly different distances and that any apparent relative motion would be a parallactic effect of the motion of the earth around the sun. The pioneer work of [John’s father] William Herschel had demonstrated orbital motion of binary stars under mutual attraction. John continued the work, re-observing known systems and discovering new ones, with detailed study of several cases, notably Gamma Virginis, and the development of methods (1833) for the determination of orbital elements. For their catalog of 380 double stars (1824) South and Herschel received the Lalande Prize of the French Academy in 1825 and the gold medal of the Astronomical Society (1826) … “James South left England and Herschel continued astronomical observations at Slough, following his father’s lead in observation of nebulae, clusters, and double stars. A monumental catalog of 2,307 nebulae and clusters, 525 being new, was issued in 1833. By 1836 he had published six catalogs of double stars, comprising 3,346 systems … “Herschel was now nearing forty and had earned almost every possible distinction in his field. He might well have remained a solitary bachelor but for his friend James Grahame, who decided he would be better off married and even picked out the girl: Margaret Brodie Stewart, daughter of Dr. Alexander Stewart, a Presbyterian divine and Gaelic scholar, who by his two wives had had a large family. Maggie, as Herschel was to call her, was good-looking, eighteen years younger than Herschel, and possessed an extremely strong character. Grahame threw the couple together; they married in 1829, were supremely happy, and had twelve children. Maggie followed Herschel everywhere, even to the wilds of Africa, and managed all his complex affairs, even to the extent of running a household of seldom less than twenty people when she was still in her early twenties. “Herschel now conceived the idea of an astronomical expedition to the southern hemisphere, possibly delaying its execution until after his mother’s death in 1832. The only possible choices of site were South America, Australia, and the Cape of Good Hope. The Cape Colony had come under British rule in 1806 as a consequence of the Napoleonic Wars. Cape Town had existed as a town since 1652 and was important as a way station for many ships en route to India. The British had established an observatory there for the ‘improvement of astronomy and navigation’ in 1820. As the result of the work of Lacaille in 1751–1753 it had an astronomical tradition and also enjoyed the technical advantage of being in the same longitude as eastern Europe, so that cooperative observations in the same meridian were possible. “On 13 November 1833 the Mountstuart Elphinstone sailed from Portsmouth with the Herschel party—John, Maggie, three children, a mechanic named John Stone, and a nurse—on board. They had a twenty-foot telescope and a seven-foot equatorially mounted refractor. They landed at Cape Town on 16 January 1834, Herschel having happily beguiled the voyage with all kinds of astronomical, oceanographical, and meteorological investigations while everyone else was prostrated with seasickness. Ten days before they landed, the newly appointed director of the Cape Observatory (H.M. astronomer at the Cape), Thomas Maclear, had arrived with his family and servant; the two were to enjoy four years of happy collaboration. “Herschel leased at £225 per annum (and subsequently purchased for £3000) an eighteen-room house called ‘The Grove,’ which he named ‘Feld-hausen’ by a German approximation to its Dutch name, in the suburb of Claremont, south of Cape Town. Within six weeks he and John Stone had the reflector erected on a spot now marked by a memorial obelisk. By 1838 he had swept the whole of the southern sky, cataloged 1,707 nebulae and clusters, and listed 2,102 pairs of binary stars. He carried out star counts, on William Herschel’s plan, of 68,948 stars in 3,000 sky areas. Herschel made micrometer measures for separation and position angle of many pairs. He produced detailed sketches and maps of several objects, including the Orion region, the Eta Carinae nebula, and the Magellanic Clouds, and extremely accurate drawings of many extragalactic and planetary nebulae. He observed lunar eclipses, and when Eta Carinae, an object whose nature is still not understood, underwent a dramatic brightening in December 1837, he recorded its behavior in detail. Herschel invented a device called an astrometer, which enabled him to compare the brightness of stars with an image of the full moon of which he could control the apparent brightness, and thus introduced numerical measurements into stellar photometry. Maclear provided him with accurate star positions, and he assisted Maclear in geodetic and tidal observations. He observed Encke’s and Halley’s comets and experimented with the actinometer and with cooking by solar heat. “Herschel and Maggie and some of the children made several trips into the nearer parts of the western Cape Colony. He helped promote exploring expeditions and galvanized the Cape Philosophical Society. His correspondence was enormous, and virtually everyone of note visited him. He drew pictures of scenery and flowers with the camera lucida, and Maggie colored some of the pictures. He did enough botany to get his name in the list of species and established systematic meteorology in the area. With several local worthies Herschel devised a new educational system for the Cape Colony, traces of which persist; and, having written memoranda from the Cape, lobbied for their acceptance when he reached home. He refused official financial aid for the expedition and was able to offer financial aid to several of his numerous brothers-in-law. On 11 March 1838 the expedition embarked on the Windsor, with Herschel conducting experiments throughout the voyage, and landed at London on 15 May 1838. “The newly created baronet rushed off to Hannover to see his Aunt Caroline, as well as Gauss, Olbers, and H. C. Schumacher. He produced numerous papers on topics ranging from iron meteors to variable stars to the structure of the eye of the shark. Many of these derived from his African experiences, particularly his plan for the reform of the nomenclature and boundaries of the constellations, which was ready by 1841. Herschel served on committees and commissions, including the Royal Commission on Standards (1838–1843), and as lord rector of Marischal College, Aberdeen, in 1842. He helped to organize worldwide meteorological and magnetic observations, as well as the geomagnetic expedition of James Clark Ross to the Antarctic. “From Herschel’s return from Africa until the mid-1840s two special scientific preoccupations stand out: the reduction of the African results and their preparation for publication, which led to numerous relatively short papers; and the researches in photography … “In 1840 the family moved from Slough to ‘Colingwood,’ a house at Hawkhurst, Kent. Herschel was then forty-eight years old and beginning to slow down. Still to come were the remaining photographic papers, a great deal of committee work, miscellaneous astronomical papers, some investigations of the phenomena of fluorescence, and thoughts on such diverse topics as meteorology, metrology (including that of the Great Pyramid), and color blindness. The Results from Africa appeared in 1847” (DSB). Norman 1056.

4to (309 x 247mm), pp. [iv: presentation and half title], xx, 452, [2], [2, ads], with lithograph frontispiece and 17 plates, some folding (minor foxing to title, frontispiece and plates). Original blind-stamped cloth, gilt-lettered spine (faded as usual, light wear at corners and extremities). Preserved in an unusually fine quarter-calf folding box.

Item #5354

Price: $12,500.00