De humani corporis fabrica, lib. VII.

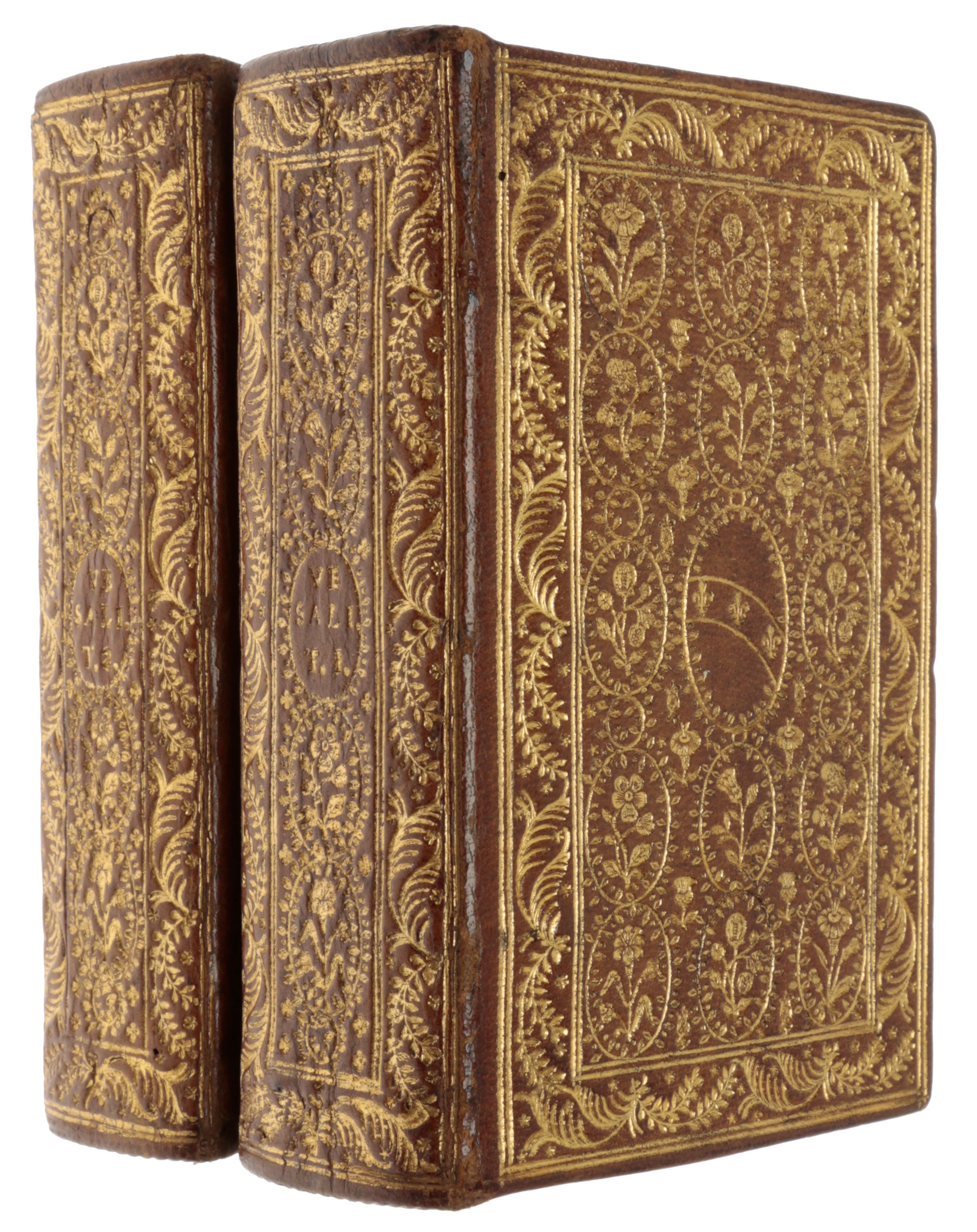

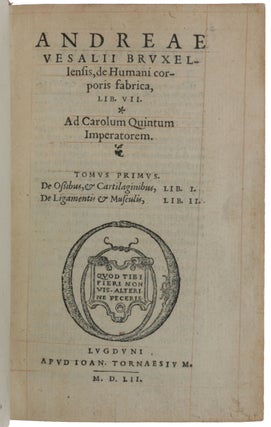

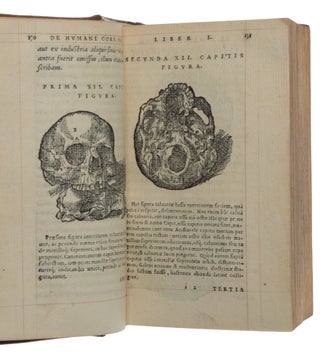

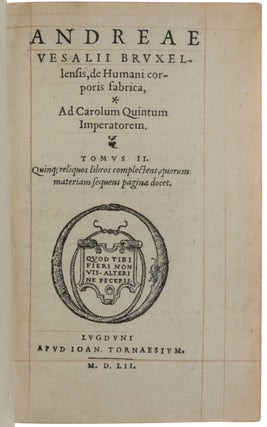

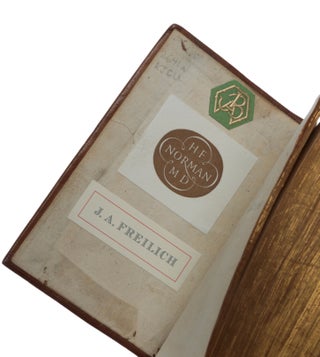

Lyons: Jean de Tournes, 1552. Second edition of the Fabrica, the Norman-Freilich copy in a superb fanfare binding for Pietro Duodo. “The work of Andreas Vesalius of Brussels constitutes one of the greatest treasures of Western civilization and culture. His masterpiece, the Humani Corporis Fabrica … established with startling suddenness the beginning of modern observational science and research. [The] author has come to be ranked with Hippocrates, Galen, Harvey and Lister among the great physicians and discoverers in the history of medicine. However, his book is not only one of the most remarkable known to science, it is one of the most noble and magnificent in the history of printing. In it, illustration, text and typography blend to achieve an unsurpassed work of creative art; the embodiment of the new spirit of the Renaissance directed towards the future with new meaning” (Saunders and O’Malley, p. 9). “No other work of the 16th century equals it, though many share its spirit of anatomical inquiry. It was translated, reissued, copied and plagiarized over and over again and its illustrations were used or copied in other medical works until the end of the 18th century” (PMM). “Published when the author was only 29 years old, the Fabrica revolutionized not only the science of anatomy but how it was taught. Throughout this encyclopedic work on the structure and workings of the human body, Vesalius provided a fuller and more detailed description of the human anatomy than any of his predecessors, correcting errors in the traditional anatomical teachings of Galen. Even more epochal than his criticism of Galen and other ... authorities was Vesalius’s assertion that the dissection of cadavers must be performed by the physician himself. As revolutionary as the contents of the Fabrica and the anatomical discoveries which it published, was its unprecedented blending of scientific exposition, art and typography” (Garrison-Morton). This unauthorized pocket-sized edition, which closely follows the text of the 1543 edition but reproduces only four of the woodcuts, was one of a series of small format editions of texts of proven success produced by Jean de Tournes I from the mid-1540s through the 1560s. During the previous decade Lyons had become a center for the publication of pocket editions of the medical classics, usually translated into French. The printer’s note on the verso of the first title explains that the edition was printed for the use of students, but clearly, “Jean de Tournes’ venture could scarcely have been a profitable one, for the Fabrica without [its] illustrations was not the same book by any means” (Cushing). Cushing noted that copies with both volumes in matching bindings are rare. Provenance: Pietro Duodo (1554-1611), Venetian ambassador to the Court of Henri IV from 1594 to 1597 (binding). This bibliophile had a portable library of which all the books (about 150 small volumes acquired during his stay in Paris) were bound in the same way, only the color of the morocco varied according to the themes: olive green or havana was reserved for works of literature, lemon for medicine and botany, and red for history, philosophy, theology and law. These bindings were once attributed to the Eve workshop and it was long thought, because of the presence of a daisy among the characteristic floral decoration, that they were made for Queen Marguerite de Valois; 19th-century shelfmark or lot label on front free endpaper to vol. I, ‘365/2’; ‘991’ in ink on front pastedown of vol. II; Haskell F. Norman (bookplate, his sale, Christie’s New York, 18 March 1998, lot 215); Joseph A. Freilich (label, his sale, Sotheby’s New York, 11 January 2001, lot 537); Christie’s, 16 June 2015. “Several motives underlay the composition and publication of the Fabrica. According to Vesalius medicine was properly composed of three parts; drugs, diet, and ‘the use of the hands,’ by which last he referred to surgical practice and especially to its necessary preliminary, a knowledge of human anatomy that could be acquired only by dissecting human bodies with one’s own hands. Through disdain of anatomy, the most fundamental aspect of medicine, or, as Vesalius phrased it, by refusal to lay their hands on the patient’s body, physicians betray their profession and are physicians only in part. “Vesalius hoped that by his example in Padua and especially by his verbal and pictorial presentation in the Fabrica he might persuade the medical world to appreciate anatomy as fundamental to all other aspects of medicine and that, through the application of his principles of investigation, a genuine knowledge of human anatomy would be achieved by others, in contrast to the more restricted traditional outlook and the uncritical acceptance of Galenic anatomy. The very word ‘fabrica’ could be interpreted as referring not only to the structure of the body but to the basic structure or foundation of the medical art as well. Thus, Vesalius directed his work toward the established physician, whom he hoped to attract to the study of anatomy as a major but neglected aspect of a true medicine and, no less important, toward those members of the medical profession who were concerned with the teaching of anatomy and might be induced to forsake their long-accepted traditional methods for those proposed by Vesalius. As anatomy was then taught, he wrote, ‘there is very little offered to the [students] that could not better be taught by a butcher in his shop.’ “The Fabrica was also written to demonstrate the fallacious character of Galenic anatomy and all that it implied. Since Galen’s anatomy was based upon the dissection and observation of animals, it was worthless as an explanation of the human structure; and since previous anatomical texts were essentially Galenic, they likewise were worthless and ought to be disregarded. Human anatomy was to be learned only by dissection and investigation of the human body, the true source of such knowledge. Nevertheless it was desirable that human dissection be accompanied by a parallel dissection of the bodies of other animals in order to show the differences in structure and hence the source of Galen’s errors. ‘Physicians ought to make use not only of the bones of man but, for the sake of Galen of those of the ape and dog.’ It was because of Vesalius that Padua became the first great center of comparative as well as of human anatomical studies, a dual interest that continued to develop under his successors Falloppio, Fabrici, and Casserio. “According to Vesalius, the student or physician ought to carry on these activities himself and should personally dissect the human body … Even the reader of the Fabrica must not be content to accept Vesalius’ descriptions without question but ought to test them by his own dissections and observations. For this purpose the descriptive chapters of the Fabrica are frequently followed by directions for making one’s own dissection of the part described so as to arrive at an independent conclusion. “Vesalius regarded the Fabrica as the gospel of a new approach to human anatomical studies and a new method of anatomical investigation. In Padua both the gospel and its explications were presented directly by the author. For those elsewhere it was presented through the Fabrica with its long and complete descriptions, its illustrative and diagrammatic guides to aid recognition of details and to supplement the reader’s possible shortage of dissection specimens, and even its indirect encouragement of body snatching if necessary. The work reflects fully Vesalius’ method of instruction from about the end of 1539 through 1542 … “The presentation of a new anatomy and anatomical method raised several problems, of which the first was that of terminology. As in the Tabulae anatomicae (1538), Vesalius continued to use terms from several languages but stressed the Greek form wherever possible. If this was not enough for clarity, an extensive description was given to localize the part with reference to other parts, and illustrations of the particular organ or structure were provided. Additionally, as a mnemonic device and for increased comprehension, anatomical structures were related to common objects, the radius, for example, being compared to the weaver’s shuttle and the trapezius muscle to the cowl of the Benedictine monks. Some of Vesalius’ terms are still in use, so that this aspect of his pedagogy plays the same role today as it did in the sixteenth century. Thus the names of two of the auditory ossicles, the incus and malleus, are derived from Vesalius’ description of them as ‘that one somewhat resembling the shape of an anvil [incus]” and “that one resembling a hammer [malleus].’ The valve of the left atrioventricular orifice, the mitral valve, ‘you may aptly compare to a bishop’s miter’ … “Owing to the larger amount of dissection material available to him, Vesalius was not compelled to follow the traditional pattern of dissection and description originally established by Mondino (1316). Consequently, book I of the Fabrica opens with a description of the bones. This arrangement was desirable since according to Vesalius the bones are the foundation of the body, the structure to which everything else must be related; and in his anatomical demonstrations he was accustomed to sketch the position of the bones on the surface of the body with charcoal in order to orient the students. The fundamental significance of the bones was further indicated by his reference to the femur, for example, as either the bone itself or the entire leg of which the bone was the basic structure. Moreover, the bones are not only supports for the body; since by their structure and formation they assist and control movement, it is necessary to recognize in them a dynamic quality that Vesalius sought to emphasize by the suggestion of movement in the poses of the skeletons … “In his description of human osteology, the subject of book I, Vesalius made some of his strongest assaults upon Galenic anatomy. He called attention to Galen’s false assertion that the human mandible is formed of two bones and demonstrated the significance of this error as reflecting a dependence upon animal sources. Likewise he pointed to the fact that the Galenic description of the sternum as formed of seven segments is true of the ape but not of the adult human sternum, which has only three. Similarly the ‘humerus, according to Galen, is with the exception only of the femur, the largest bone of the body. Nevertheless the fibula and tibia are distinctly of greater length than the humerus.’ In addition to such criticisms, there is extensive description of osteological detail, which, because much of it was wholly novel, required detailed illustrations, elaborately related by letter and number to the text. Despite some errors of description and occasional references to animal anatomy in the Galenic tradition, this first book represents Vesalian anatomy on the highest level. It concludes with a remarkable chapter on the procedure for preparation of the bones and articulation of the skeleton, since it was essential that a skeleton always be available at the dissection. Such a skeleton is a central figure of the title page. “As he had done with the bones, so Vesalius endeavored in book II to identify and give the fullest possible description of every muscle and its function … The first two books represent the major Vesalian achievement in terms of accuracy of description and present the most telling blows against Galenic anatomy. In book II Vesalius also most frequently provided chapters dealing with the dissection procedure used to arrive at his conclusions. The description of the vascular system in book III is less satisfactory because of Vesalius’ failure to master the complexities of distribution of the vessels and because of the close relationship of the vascular system to Galenic physiology. Vesalius was compelled to subscribe to this for lack of any other theories. The errors in the Vesalian description of the distribution of the vessels are due to his reliance on Galen, as the only other writer to have attempted such a description in detail, and to the difficulty of discovering anew the entire vascular arrangement in rapidly putrefying human material. Although Vesalius was partly successful, as, for example, in his account of the interior mesenteric and the hemorrhoidal veins, there are many indications that he was compelled to rely for much of his account on the anatomy of animals. This is clearly apparent in the illustration of the “arterial man,” where the arrangement of the branchings of the aortic arch actually illustrate simian anatomy. “Book IV provides an account of the nervous system. It is introduced by an attempt to clarify and limit the meaning of the word ‘nerve’ to the vehicle transmitting sensation and motion, because ‘leading anatomists declare that there are three kinds of nerve’: ligament, tendon, and aponeurosis. ‘From dissection of the body it is clear that no nerve arises from the heart as it seemed to Aristotle in particular and to no few others.’ Although Vesalius was obliged to accept the Galenic explanation of nervous action as induced by animal spirit distributed through the nerves from the brain, his examination of the optic nerve led him to the conclusion that the nerves were not hollow, as Galen had asserted. ‘I inspected the nerves carefully, treating them with warm water, but I was unable to discover a passage of that sort in the whole course of the nerve.’ “Vesalius accepted Galen’s classification of the cranial nerves into seven pairs even though he recognized more than that number and described a portion of the trochlear nerve. To avoid confusion he declared that he would ‘not depart from the enumeration of the cranial nerves that was established by the ancients.’ Although he was not wholly successful in his efforts to trace the cranial nerves to their origins, and despite some confusion about their peripheral distribution, the level of knowledge in the text and illustrations was well above that of contemporary works and was not to be surpassed for about a generation. Vesalius was more successful in tracing the spinal nerves, but on the whole the account of the nerves must be described as being of lesser quality than some of the other books. “The description of the abdominal organs in book V is detailed and reasonably accurate. Since he knew of no alternative Vesalius accepted that aspect of Galen’s physiology which placed the manufacture of the blood in the liver. Nevertheless he denied not only that the vena cava takes its origin from the liver but also that the liver is composed of concreted blood. Here his strongest blow against Galen and medieval Galenic tradition was his denial, based on human and comparative anatomy, of the current belief in the liver’s multiple (usually five) lobes. According to Vesalius the number of lobes increased with the descent in the chain of animal life. In man the liver had a single mass, while the livers of monkeys, dogs, sheep, and other animals had multiple lobes that became more numerous and more clearly apparent. This difference once again proved the error of dependence upon nonhuman materials. “Vesalius also denied the erroneous Galenic belief that there was a bile duct opening into the stomach as well as one into the duodenum. In regard to the position of the kidneys, he had begun to move away from the erroneous view expressed in the Tabulae anatomicae that the right kidney was placed higher than the left. Although this error is illustrated in the Fabrica, the text declares that the reverse could also be true. Despite this partial error of traditionalism. Vesalius denied a second traditional opinion that the urine passed through the kidneys by means of a filter device. The filter theory had also been denied by Berengario da Carpi; but Vesalius went a step further by asserting that the ‘serous blood’ was deliberately selected or drawn into the kidney’s membranous body and its ‘branchings’ to be freed of its ‘serous humor’ in the same way that the vena cava was able to select and acquire blood from the portal vein, and that the excrement was then carried by the ureters to the bladder. “The book ends with a discussion of human generation and the organs of reproduction. Although Vesalius denied the medieval doctrine of the seven-celled uterus and declared the traditional representation of the horned uterus to result from the use of animal specimens, his description of the fetus and fetal apparatus was of less significance, reflecting, as he admitted, the lack of sufficient pregnant human specimens. “Book VI describes the organs of the thorax. It is chiefly important for the description of the heart, which Vesalius described as approaching the nature of muscle in appearance, although it could not be true muscle since muscle supplied voluntary motion and the motion of the heart was involuntary. In this instance Vesalian principle bowed to Galenic theory, and recognition of the muscular substance of the heart had to await William Harvey’s investigations in the next century. “Like all his contemporaries Vesalius regarded the heart as formed of two chambers or ventricles. The right atrium was not considered to be a chamber but rather a continuation of the inferior and superior venae cavae, considered as a single, extended vessel; and the left atrium was thought to be part of the pulmonary vein. According to Galen the ventricles were divided by a midwall containing minute openings or pores through which the blood passed or seeped from the right ventricle into the left, an opinion that Vesalius strongly questioned even though by implication he was casting doubt on Galen’s cardiovascular physiology. ‘The septum of the ventricles having been formed, as I said, of the very thick substance of the heart … none of its pits-at least insofar as can be ascertained by the senses-penetrates from the right ventricle into the left. Thus we are compelled to astonishment at the industry of the Creator who causes the blood to sweat through from the right ventricle into the left through passages which escape our sight.’ Finally Vesalius gave strong expression to his opinion of ecclesiastical censorship over the question of the heart as the site of the soul. After referring to the opinions of the major ancient philosophers on the location of the soul, he continued: ‘Lest I come into collision here with some scandalmonger or censor of heresy, I shall wholly abstain from consideration of the divisions of the soul and their locations, since today… you will find a great many censors of our very holy and true religion. If they hear someone murmur something about the opinions of Plato, Aristotle or his interpreters, or of Galen regarding the soul, even in anatomy where these matters especially ought to be examined, they immediately judge him to be suspect in his faith and somewhat doubtful about the soul’s immortality. They do not understand that this is a necessity for physicians if they desire to engage properly in their art …’ “The seventh and final book provides a description of the anatomy of the brain, accompanied by a series of detailed illustrations revealing the successive steps in its dissection. Until the time of Vesalius, illustrations of the brain and any accompanying text usually stressed the localization of intellectual activities in the ventricles, with perception in the anterior ventricles, judgment in the middle, and memory in the posterior. Sensation and motion were considered the work of animal spirit produced in a fine network of arteries at the base of the brain, the rete mirabile. The existence of the rete mirabile in the human brain had been questioned by Berengario da Carpi. It was now firmly denied by Vesalius, who showed the belief in this organ to have been the result of dissection of animals, since such an arterial network does in fact exist in ungulates. Vesalius was also the first to state that the ventricles had no function except the collection of fluid. Moreover, he denied that the mind could be split up into the separate mental faculties hitherto attributed to it. As a corollary he intimated that although animal spirit affected sensation and motion, it had nothing at all to do with mental activity-in short he suggested a divorce between the physical and mental animal. The discussion of the brain is concluded by a chapter on the procedure to be followed for its dissection and by a final, separate section on experiments in vivisection, derived and developed mostly from experiments described by Galen. The separate treatment of this latter material indicated a recognition of physiology as a discipline distinct from anatomy. “In the Fabrica Vesalius made many contributions to the body of anatomical knowledge, by description of structures hitherto unknown, by detailed descriptions of structures known only in the most elementary terms, and by the correction of erroneous descriptions. Despite his many errors his contribution was far greater than that of any previous author, and for a considerable time all anatomists, even those unsympathetic to him, were compelled to refer to the Fabrica. Its success and influence can be measured by the shrillness of Galenic apologists, by the plentiful but unacknowledged borrowings of many, and by the avowed indebtedness of the generous few, such as Falloppio. Although Colombo, Falloppio, and Eustachi corrected a number of Vesalius’ errors and in some respects advanced beyond him in their anatomical knowledge, Colombo published his anatomical studies sixteen years after the appearance of the Fabrica, Falloppio eighteen, and Eustachi twenty. Furthermore, they relied heavily upon Vesalius’ work, the detailed nature of which made it relatively easy for others to correct or to make further contributions. Although their accomplishments deserve recognition they were built upon Vesalian foundations. “More important than the anatomical information contained in the Fabrica was the scientific principle enunciated therein. This was beyond criticism, fundamental to anatomical research, and has remained so. It was not difficult to demonstrate Galen’s errors of anatomy, but such a demonstration was only a means to an end. Its significance lay in the reason for those errors: Galen’s attempt to project the anatomy of animals upon the human body. From time to time others had pointed to Galenic errors, but no one had proposed a consistent policy of doubting the authority of Galen or of any other recognized authority until the only true source of anatomical knowledge—dissection and observation of the human structure—had been tested. With the publication of the Fabrica all major investigators of anatomy were compelled to recognize the new principle, even though at first some paid no more than lip service to it … “Advanced by the successive occupants of the anatomical chair at Padua (Realdo Colombo, Gabriele Falloppio, and Fabrici), the Vesalian principles were thence diffused through Italy and later throughout western Europe. By the beginning of the seventeenth century, with the exception of a few conservative centers such as Paris and some parts of the Empire, Vesalian anatomy had gained both academic and general support” (DSB). “The present copy, one of about 100 small-format editions purchased by Pietro Duodo during his ambassadorship in Paris, whose nearly uniform bindings he commissioned from a single Parisian atelier, is undoubtedly the finest copy extant of the 1552 Vesalius. From their first appearance on the market at the end of the 18th century, these exquisite little red-ruled books with their semis of floral medallions were attributed to the library of Marguerite de Valois, apparently on no other grounds than the daisies that liberally decorate their covers. In 1925 Ludovic Bouland identified the true owner as the Venetian diplomat Pietro Duodo, but the attribution to a specific bindery remained speculative, the execution of the bindings being generally ascribed to the catch-all shop of Clovis Eve. The use of the same set of tools on all of the bindings bearing Duodo’s arms and device, as well as the uniformity of their sewing structure, show that Duodo commissioned all of his bindings from the same atelier, very likely all at once or in two or three large batches. For example, nearly all of Duodo’s bindings contain an identical system of enlacement, the ends of the sewing bands forming a ‘t’ shape visible under the pastedown endleaves, and the endleaves invariably consist of a sheet folded in quarto to form four leaves including the pastedown, all from the same paper stock, with watermark Briquet 9273 (cf. Needham). In 1979 a vase tool used on only two known examples of Duodo’s books was identified by Bernard Breslauer (Martin Breslauer catalogues 104/195) as belonging to the bindery named by G. D. Hobson (in Les Reliures a la fanfare) the ‘Atelier de la seconde Palmette’, the most prolific of the late 16th and early 17th-century Parisian binderies specializing in the ‘fanfare’ decor. Needham points out that the large number of similarly decorated small-format bindings of this period, often on devotional texts, that are without Duodo’s arms and bear slightly different tools points to the likelihood that the distinctive design chosen by Duodo was modelled after an existing binding style, rather than being the paradigm for subsequent imitations, as the term ‘Duodo-style’ would imply. PMM 71; Grolier, Medicine 18A; Dibner 122 (all for the first edition); Norman 2138; Adams V-604; Cartier De Tournes 235; Cushing VI.A.-2 (noting that copies with both volumes in matching bindings are rare); NLM/Durling 4578; Waller 9900; Wellcome I, 6561; Bouland, ‘Livres aux armes de Pierre Duodo’, Bulletin du bibliophile (1920), pp. 66-80; Bibliothèque Raphael Esmerian, Part I (6 June 1972), pp. 94-96, lots 59-61; Needham, Twelve Centuries of Bookbinding 98; M. von Arnim, ed., Europäische Einbandkunst aus sechs Jahrhunderten, 1992, p. 72.

“As an active diplomat who had already resided in Poland and was later to serve as ambassador to Prague, London and the Vatican, Duodo’s aim in his Paris buying was to form a portable gentleman’s library. The 90 titles (in 133 volumes) recorded by Raphael Esmerian reveal a typical humanist private library. Most of the texts are in Greek or Latin, and the subject areas covered, distinguished by differently colored morocco, are predominantly literary (72 volumes, olive-brown morocco), or relate to theology philosophy and history (46 volumes, red morocco), but also include a small group of books on botany and medicine (15 volumes, citron morocco). Duodo apparently never entered into possession of his freshly bound library being suddenly recalled to Italy in 1597, and the books remained in Paris, untouched for 200 years, until at the time of the Revolution they gradually began to appear on the market. They were immediately valued by collectors, largely because of the mistakenly attributed provenance, making it probable that the extant recorded copies represent a major proportion of the original library” (Norman sale catalogue).

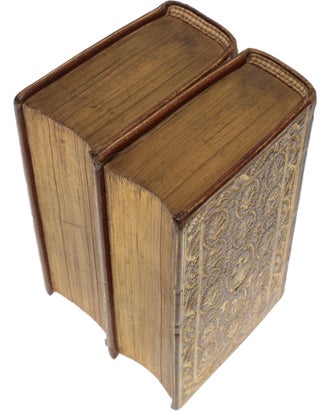

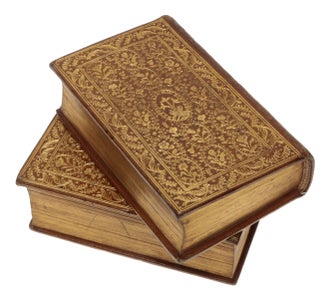

Two vols., 16mo (118 x 72mm and [vol. II] 120 x 74mm; binding size: 123 x 81mm and [vol. II] 127 x 80mm), pp. [1], 2-458, [54], 1-523, [45] and [vol. II] [1], 2-833, [79], four small woodcuts of the cranium on i1v and i2r-v, printer’s devices on titles (Cartier ‘Vipres o.’) and on versos of last leaf in vol. I and penultimate leaf in vol. II (Cartier ‘Prisme d’), six-line woodcut arabesque initials, matching woodcut head-pieces, error on printer’s note on a1v of vol. I corrected in ink, perhaps by the printer, ruled in red throughout (lower fore-corner of vol. I title a little frayed, short closed marginal tear to II:z8). Bound c. 1594-1597 for Pietro Duodo by the Parisian ‘Atelier de la seconde palmette’ in gold-tooled citron morocco, covers with a border of leafy sprays surrounding a panel filled with laurel-branch medallions around one of six different floral tools, each cover centred with a larger medallion containing Duodo’s arms on the upper covers, and, on the lower covers, Duodo’s device and motto, flat spines similarly gilt with four flower medallions, author’s name and volume number tooled in central medallion, gilt edges. Modern cloth folding cases.

Item #5373

Price: $385,000.00