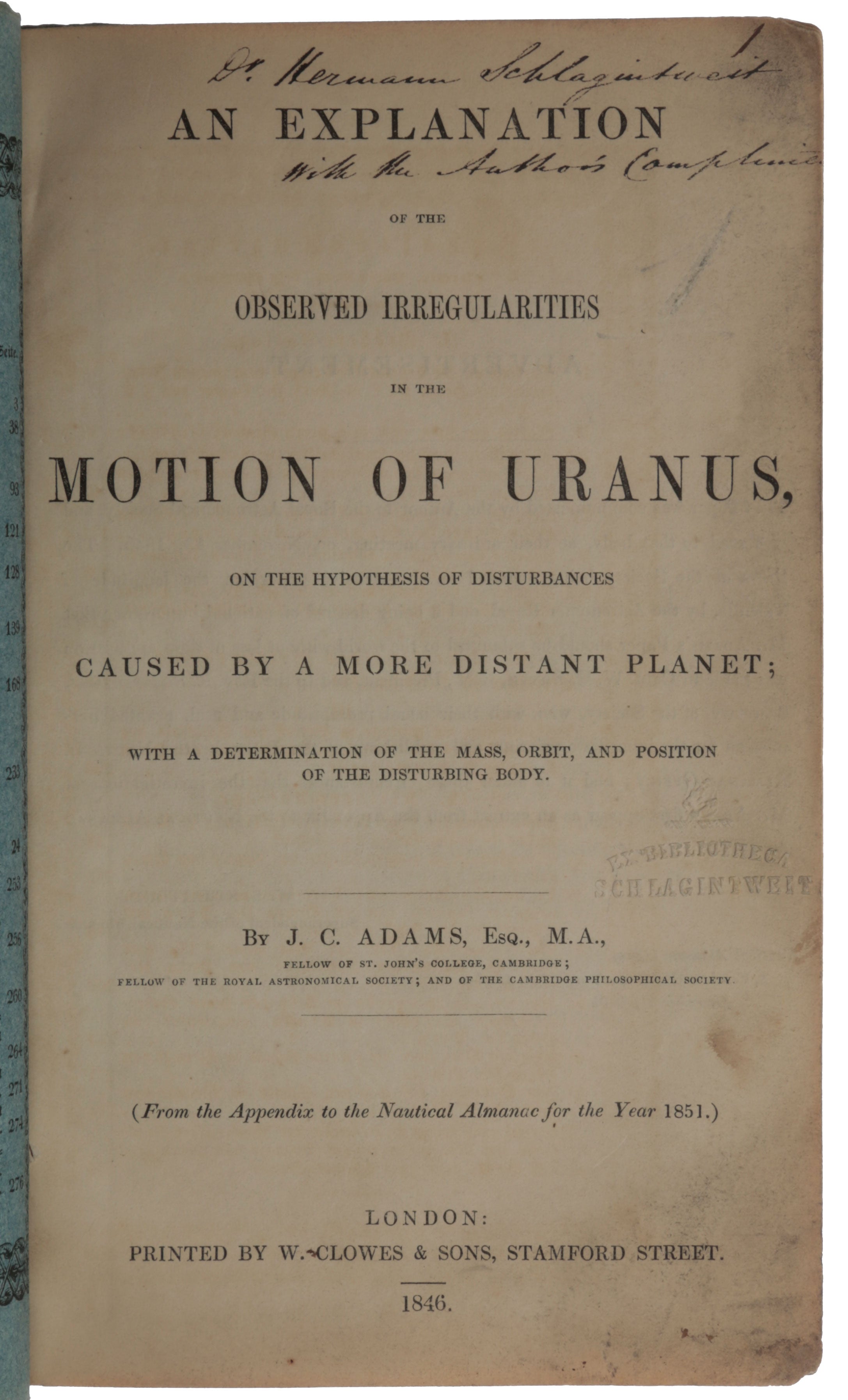

An Explanation of the Observed Irregularities in the Motion of Uranus, on the Hypothesis of Disturbances caused by a more Distant Planet; with a determination of the mass, orbit and position of the disturbing body. (From the Appendix to the Nautical Almanac for the year 1851.)

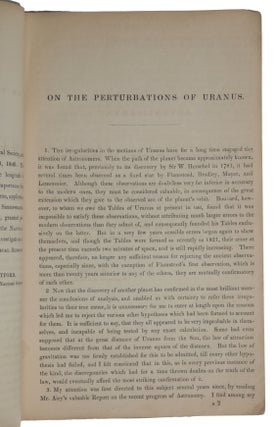

London: W. Clowes & Sons, 1846. First separate edition, presentation copy inscribed by Adams, of the discovery of Neptune, “undeniably one of the major scientific events of the nineteenth century” (Lequeux, p. 22). Adams (1819-92) and the French astronomer Urban Le Verrier (1811-77) independently predicted the existence and position of Neptune using Newton’s gravitational theory, and the existence of the planet was quickly confirmed by observation. “In this pamphlet Adams had postulated mathematically the existence of an unknown planet from its gravitational manifestations. Le Verrier simultaneously and independently made the same discovery. J.G. Galle found the planet, Neptune, on the first night it was sought, on the basis of Le Verrier’s prediction” (Dibner). “Adams began his investigation of Uranus in 1843, and in 1845 sent his calculations and observations to the Astronomer Royal, George Biddell Airy, who failed to recognise the importance of the paper. In 1846, Urbain Jean Joseph Le Verrier published his own research and reached the same conclusion, leading to the immediate identification of Neptune by J.G. Galle. Only then was Adams’ work published, leading to a bitter dispute over priority” (Norman). ABPC/RBH list seven copies in the last 40 years, but only one presentation copy (Christie’s, 1994). Provenance: Presentation copy, inscribed by Adams to German explorer Hermann Schlagintweit (1826-82); title page with blind stamp from the Schlagintweit library. Following the discovery of Uranus by William Herschel (1738-1822) in 1781, the Bureau of Longitudes, headed by Pierre-Simon Laplace (1749-1827), began the task of computing tables of the positions of the planets over time. Laplace’s student Alexis Bouvard (1767-1843) was assigned the task of calculating the positions of the three giant planets, Jupiter, Saturn and Uranus. The calculation of the tables for Jupiter and Saturn proved to be relatively straightforward, but even after taking into account the perturbations caused by the other planets, Bouvard could not derive a set of orbital elements that would successfully account for the movements of Uranus during the entire period over which it had been observed. The English astronomer Thomas Hussey (1792-1854) discussed with Bouvard the possibility that the discrepancies might be due to another planet that was perturbing Uranus, and Hussey wrote to Geoge Biddell Airy (1801-92) on 17 November 1834 to ask his opinion of the idea (Airy was appointed Astronomer Royal in the following year). Airy replied on 23 November that, in his opinion, there was insufficient information to draw any firm conclusion. Following Alexis Bouvard’s death, his nephew Eugène was charged by the Bureau of longitudes to work on new tables of the planets. He too found discrepancies which he believed were due to perturbations by an unknown planet, and wrote to Airy on 6 October 1837 to ask his opinion. Airy replied on 12 October, again doubting the existence of an unknown planet, and adding that “If [the discrepancies] be the effect of any unseen body, it will be nearly impossible ever to find out its place.” Adams became aware of the Uranus problem on 3 July 1841 when he read a copy of Airy’s 1832 Report on the Progress of Astronomy. He noted in his diary: “Formed a design … of investigating, as soon as possible, after taking my degree, the irregularities of the motion of Uranus, which are not yet accounted for, in order to find whether they may be attributed to the action of an undiscovered planet beyond it.” Adams was at this time still an undergraduate at St. John’s College, Cambridge, and he did not begin working on the problem until he completed his degree in the summer of 1843. He began by requesting from Professor James Challis (1803-82), director of the Cambridge University Observatory, further observational data on Uranus’ positions as observed at the Royal Greenwich Observatory. Challis, on 13 February 1844, requested the data from Airy on behalf of his ‘young friend’, and Airy supplied it on 15 February. As a first approximation, Adams assumed that the unknown planet’s distance would accord with Bode’s law, an empirical relationship that had worked well for all the known planets; Bode’s law put the unknown planet at a mean distance of about 38 astronomical units, twice Uranus’ distance. Busy with tutoring and performing his other ‘important duties’ at the college, Adams worked on the Uranus problem mainly during his vacations in Cornwall, and it was not until mid-September of 1845 that Adams was able to communicate to Challis ‘the final values which I had obtained for the mass, heliocentric longitude, and elements of the orbit of the assumed planet.’ Challis advised him to communicate his results to Airy. Adams called on Airy, unannounced, at Greenwich on 21 October but Airy was at dinner and seems not to have been informed of Adams’ visit. Adams left feeling discouraged, but left a manuscript of his solution for Airy. Airy wrote to Adams on 5 November requesting further information. Adams drafted a response, dated 13 November, in which he started by apologizing for calling on Airy at an unreasonable hour, and then wrote: “The paper I then left contained merely a statement of the results of my calculation; I will now, if you will allow me, trouble you with a short sketch of the method used in obtaining them” (Hutchins, p. 121). But Adams never sent this letter, perhaps because he decided not to reply until his improvements to the theory were complete, and in fact he did not write again to Airy until 2 September 1846. This delay almost certainly cost him the honour of being the first discoverer of Neptune. In France, parallel developments were in progress, entirely independent (and unaware) of the English work. Lacking confidence in Eugène Bouvard, whose measurements at the eclipse expedition of 1842 had been of poor quality, François Arago (1786-1853), director of the Paris Observatory, enlisted the assistance of Le Verrier at the École Polytechnique in the autumn of 1845, who was already known for his calculations of the orbits of comets. Le Verrier worked quickly, presenting his preliminary calculations to the Academy of Sciences on 1 June 1846. On reading the published version of Le Verrier’s memoir, Airy immediately realized the coincidence with Adams’ predictions, and decided that urgent action was necessary. He wrote to Le Verrier on 26 June to ask for further clarifications, at the same time sending him additional Greenwich observations. Le Verrier thanked Airy for his assistance, and responded to Airy’s specific questions. He even proposed to communicate the orbital elements of the perturbing planet but, for reasons that remain rather mysterious, Airy declined Le Verrier’s offer. On 9 July Airy asked Challis to search for the planet, and Challis began to do so on 29 July, making use of ‘a paper drawn up for me by Mr. Adams’. Challis admitted to Airy in a letter of 12 October that he had unwittingly observed the planet on 30 July and again on 12 August, but had failed at the time to compare the two observations and so failed to notice the change in position which would have confirmed that it was a planet (although he did so later). On August 31 1846, Le Verrier presented a second paper to the Academy of Sciences, describing his methods and a giving a prediction of where the planet ought to be found. Adams wrote to Airy’s assistant Main (Airy was travelling) on 7 September with his analysis of this important paper. Le Verrier contacted several foreign astronomers in an effort to enlist a powerful telescope in the search (there were at the time no suitable instruments at the Paris Observatory itself). Among them was Johann Gottfried Galle (1812-1910), of the Berlin Observatory, to whom Le Verrier wrote on 18 September, the letter reaching Galle on 23 September. Galle found the planet immediately, on the night of 23/24 September, and wrote to Le Verrier two days later to inform him of his discovery. Less than two weeks later, on 3 October, Sir John Herschel (1792-1871) published a letter in the journal The Athenaeum in which he stated that he had had confidence in Le Verrier’s calculations only because they had been corroborated by those of Adams. On 5 October 1846, Airy wrote to Le Verrier: “I do not know whether you are aware that collateral researches had been going on in England, and that they had led precisely to the same result as yours.” For his part, Challis wrote on 15 October in The Athenaeum, giving details about his observations and maintaining that he had seen on 12 August in the region of the sky where Adams had indicated the perturbing planet, an object that was not where it had been on 30 July. The publication of these letters from England excited considerable alarm in France. Arago defended Le Verrier’s priority in the discovery before the Academy on 19 October, alleging justly that the English had not published anything and that “there exists only one rational and just way to write the history of science: that is, to rely exclusively on publications having a definite date; beyond that, everything is confusion and obscurity.” Airy, in a long presentation given before the Royal Astronomical Society on 13 November 1846, put Adams and Le Verrier on an equal footing (‘Account of some circumstances historically connected with the discovery of the Planet exterior to Uranus,’ Monthly notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Vol. VII, no. 9, November 13, 1846, pp. 121-44). Adams himself publicly acknowledged Le Verrier’s credit in ‘An explanation of the observed irregularities in the motion of Uranus’: “I mention these dates merely to show that my results were arrived at independently, and previously to the publication of those of M. Le Verrier, and not with the intention of interfering with his just claims to the honours of the discovery; for there is no doubt that his researches were first published to the world, and led to the actual discovery of the planet by Dr. Galle, so that the facts stated above cannot detract, in the slightest degree, from the credit due to M. Le Verrier” (p. 5). Adams could have had the honour of being the first discoverer of Neptune, but for his own diffidence and social ineptness (and probable Asperger syndrome – see Sheehan & Thurber), Airy’s failure to take Adams’ work seriously (Adams was relatively unknown when he first approached Airy and Airy believed that “it will be nearly impossible ever to find out” the position of the planet), and Challis’ failure to analyze his own observations adequately. But in the end Adams held no bitterness towards Challis or Airy: “I could not expect however that practical astronomers, who were already fully occupied with important labours, would feel as much confidence in the results of my investigations, as I myself did” (letter to Airy, 18 November 1846). In 1847 Adams published a detailed account of his work as an appendix entitled ‘On the Perturbations of Uranus’ to the Nautical Almanac and Astronomical Ephemeris for 1851 (pp. 265-93). This was also issued as the separate monograph offered here. On the title verso is printed a statement explaining that Adams’ paper was being published as part of the Nautical Almanac because the Royal Astronomical Society was then engaged in another publishing project. In 1849 Hermann Schlagintweit and his brother Adolf began to plan an expedition to the Himalayas which would necessarily take them through British territories. To facilitate this they nurtured ties with the British scientific and political establishment, and visited England in 1850/51, presenting themselves to many of the British naturalists and science administrators who would later support their appointment to British India. They also visited Oxford and Cambridge, where they met Adams, among other distinguished scientists (letter from Hermann Schlagintweit to Adams, 5 January 1851 – see von Brescius, p. 50). Dibner, Heralds of Science, 16; Evans 24; Honeyman 14; Norman 7; Sparrow, Milestones 1 (later printing). Hutchins, British University Observatories 1772-1939 (2008). Lequeux, Leverrier: Magnificent and Detestable Astronomer (2013). Sheehan & Thurber, ‘John Couch Adams’s Asperger syndrome and the British non-discovery of Neptune,’ Notes and Records of the Royal Society 61 (2007), pp. 285-300. Von Brescius, German Science in the Age of Empire, 2019.

8vo (227 x 145mm), pp. 31, [1]. Blue wrappers taken from a German journal dated 1822, probably by Schlagintweit (the work was issued in self-wrappers). A fine copy.

Item #5419

Price: $22,500.00