Osteology of Deinonychus antirrhopus, an Unusual Therapod from the Lower Cretaceous of Montana. Bulletin 30. Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University.

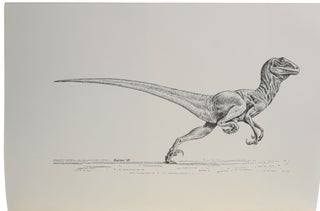

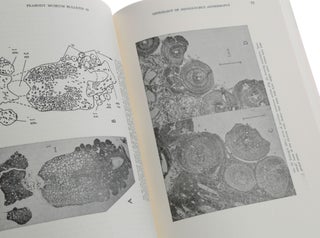

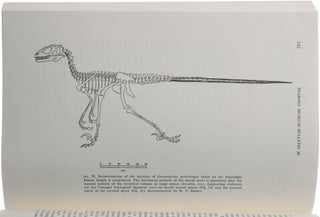

New Haven, Connecticut: n.p., July 1969. First edition, very rare, of arguably the single most important work on dinosaurs, by “the most influential palaeontologist of the second half of the 20th century” (Dodson & Gingerich). Prior to Ostrom’s work, dinosaurs were largely depicted as slow-witted, slow-moving, cold-blooded reptiles. This revolutionary monograph upended decades of thinking about dinosaur physiology, revealing them as active and agile, with the fast metabolisms of mammals and birds. “The functional morphology of the dinosaur (species Deinonychus antirrhopus) implied an upright posture and actively predacious habits at odds with the perception that dinosaurs were cold-blooded and sluggish. Ostrom later concluded that the creature must have been warm-blooded, reviving an idea posited during the early days of paleontology and thereby revolutionizing the field” (Britannica). “Dinosaurs had begun to look a lot more interesting one afternoon in late August, 1964, near Bridger, Montana. Ostrom and his assistant Grant E. Meyer had been walking a landscape of prairie punctuated with rocky, eroding outcrops, considering sites for the following summer’s fieldwork, when they spotted a large, clawed dinosaur hand protruding from the earth on a slope just below them. They scrambled down, dropped to their knees beside it, and because they hadn’t brought their toolkit, began digging excitedly with their hands, and then with their jack-knives, turning up a scattering of the serrated teeth of a predator. Next day, returning with proper tools, they unearthed an astonishing foot. Two of three toes had ordinary claws. But from the innermost toe, a sharp sickle-shaped claw curved murderously up and out. It had a slashing arc, Ostrom later calculated, of 180 degrees. Hence the eventual name Deinonychus, or ‘terrible claw.’ Ostrom and his crew spent two full field seasons digging at the site and three years in study and reconstruction at the Peabody, working with more than a thousand bones from at least four individuals of the same species. Then in 1969, Ostrom announced what he called a ‘grandiose’ conclusion: that foot was ‘perhaps the most revealing bit of anatomical evidence’ in decades about how dinosaurs really behaved. In place of the plodding, cold-blooded dinosaur stereotype, Deinonychus ‘must have been a fleet-footed, highly predaceous, extremely agile, and very active animal, sensitive to many stimuli and quick in its responses,’ Ostrom wrote. The ‘dinosaur renaissance,’ as Robert Bakker later dubbed it, had begun. Bakker had been a student member of the 1964 Montana expedition, and he contributed a drawing to Ostrom’s paper [offered here] showing a fleshed-out Deinonychus in full sprint. The ‘terrible claw’ on the hind legs was lifted up and out of the way of its feet, keeping it sharp. That drawing would soon become the icon of the new dinosaur” (Conniff).“This dinosaur is alert, intelligent-looking, light on its feet, and very swift ... like all great works of art that build on past visions, Bakker’s drawing completely transcended its forerunners, so that in a very real way it had no precedent. It is probably the single most memorable image of modern dinosaur literature, and it is not surprising that it marks the beginning of a new era in dinosaur restoration” (Ashworth 49). No copies in auction records, and scarce even in institutional collections (COPAC records British Library and National Library of Scotland only). “In the summer of 1964, a paleontology dig team from Yale University’s Peabody Museum, led by Prof. John Ostrom, were prospecting for fossils within the Cloverly Formation in northern Wyoming and south-central Montana. Unlike the Morrison Formation of the late Jurassic Period and the Hell Creek Formation of the late Cretaceous Period, both of which have been intensely studied for decades and which are both world-famous for the large amounts of dinosaur bones which have been unearthed there, the Cloverly Formation of the middle Cretaceous Period is not well-known or well-studied. Very little research had been done on these rock layers, and very few fossils had been unearthed here. Ostrom’s 1964 survey hoped to shed a little bit more light on this otherwise obscure section of Mesozoic time … “About seven miles southeast of the town of Bridger, Montana, Ostrom would make a remarkable discovery. On August 29, 1964 – the very last day of the dig season – Ostrom was being shown around by Grant Meyer, a senior member of the dig team, to all of the sites that he and his associates had taken note of as places where they ought to dig for fossils during the next time that they came out this way. A large cone-shaped hill known as ‘the Shrine’ was the last stop on Meyer’s list of places to visit that day. At this hill, close to where the cars were parked, Ostrom spotted a claw sticking out of the ground. Since all of the digging tools had been packed up for the day, Ostrom got down on his hands and knees and scraped away at the dirt using his fingernails. The two of them quickly realized that they had found the hand of a meat-eating dinosaur, with three long fingers, each one tipped with a massive eagle-like talon. Nearby was another large claw, which Ostrom initially thought belonged to the hand, but was later shown to have been fitted onto one of the toes of the foot; this claw was substantially larger than the claws on the other toes. Most curiously of all were sections of the tail, in which the vertebrae appeared to have been held in place by longitudinal rows of stiffened rod-like tendons. In life, this would have made the tail stiff and rigid. “Ostrom and his team spent as much time as they could digging up the specimens, but their time was running out and they couldn’t stay any longer. They realized that they would have to come back again to this spot next year and pick up where they left off. In fact, Ostrom and his associates came back twice, in the summers of 1965 and 1966. They realized that they had not just one but several skeletons, presumably from the same species … “It took John Ostrom and the Peabody Museum’s fossil preparators nearly three years to prepare all of the fossils and do a comprehensive assessment of everything that had been found. It was during his research that Ostrom came across some curious references to fossils of a small meat-eating dinosaur which Barnum Brown had found in south-central Montana back in the early 1930s. These bones apparently bore a strong similarity to the fossils which he and his team had recently unearthed. They had been stashed away in the AMNH’s fossils collections, and it seems that nobody had bothered to look at them since. Ostrom decided that he needed to investigate. Dr. Edwin H. Colbert, a paleontologist from the AMNH who gained notoriety for his research on the Triassic meat-eating dinosaur Coelophysis, forwarded the bones and Barnum Brown’s field records to Dr. Ostrom in New Haven to examine. These bones had only been partially prepared, and there was no ‘treatment report’ (a report made by paleontologists and fossil preparators concerning what work had been done on the bones since they were collected) accompanying them. However, when he examined the bones, Ostrom recognized a strong similarity between the fossils which Brown had found back in the early 1930s and the fossils which he and his team had found recently. They undoubtedly came from the same animal … He officially named the animal Deinonychus, meaning ‘terrible claw’. The species name antirrhopus meant ‘counter-balance’, in reference to its long stiffened tail which it presumably used as a balancing pole to keep its balance while making sharp turns and leaping into the air … “In July 1969, Ostrom published a comprehensive assessment of Deinonychus’ skeleton, describing everything in extremely specific detail; the entire report measured 172 pages long … “Deinonychus measured about 3 feet tall and 10 feet long – somewhat larger than your average raptor. It was by no means the largest meat-eating dinosaur that had been found, or the smallest for that matter, but at the time of its discovery, it was the most intriguing. The things which identified Deinonychus and other ‘raptor’ dinosaurs are the large ‘killing claws’ on the feet. These enlarged hook-shaped toe claws, which were twice as large or larger than the other claws on the feet, were clearly used for a distinctive method of attacking and killing its prey. This implied that this animal lived a very active lifestyle. Indeed, the entire animal’s anatomy seemed to radiate an air of athleticism, possessing a light greyhound-like frame with slight delicate bird-like bones, large grasping hands, and most curious of all, a long tail which had been stiffened into a pole by the addition of row-upon-row of ossified tendons running all along its length, except for where the tail attached to the hip, allowing the tail to pivot at the tail’s base. In Ostrom’s mind, this tail served much the same function as a balancing pole used by a tightrope-walker so that the animal could maintain its balance when leaping onto its prey or making sharp tight turns when running at high speed … “John Ostrom himself referred to the discovery of Deinonychus as one of the most important discoveries in paleontology, because it was such a game-changer for everything that we assumed we knew about dinosaurs. In John Ostrom’s words, ‘Deinonychus certainly opened up a whole new window in viewing these animals. This animal clearly indicated extreme agility, activity, perhaps even intelligence, but these were very very sophisticated animals unlike our previous image of what dinosaurs were about’. “The discovery of Deinonychus kick-started a sea-change in paleontology. Beginning in the early 1970s, paleontologists were forced to re-think pretty much everything that they thought they knew about dinosaurs. Images and perceptions of dinosaurs as slow stupid plodders, which had been regarded as scientific dogma ever since the 1820s, were thrown out the window. This fervent period of iconoclastic scientific re-examination would become known as ‘the Dinosaur Renaissance’ … “Increasingly, dinosaurs came to be seen as energetic active animals, more akin in their physiology to many hot-blooded mammals alive today than to sluggish cold-blooded reptiles. This led to an interesting question – could it be possible that dinosaurs were also warm-blooded? This couldn’t be, because dinosaurs were reptiles, and all reptiles alive today are cold-blooded. However, scientists observed that birds almost certainly evolved directly from dinosaurs, and all birds alive today are hot-blooded. So, could it have been possible that dinosaurs, like their bird descendants, were warm-blooded too? The debate whether dinosaurs were cold-blooded or hot-blooded would prove to be one of the most contentious in paleontology for decades afterwards, and it still has not been conclusively resolved … “From 1969 until 1993, Deinonychus was one of the most famous dinosaurs in the world, achieving celebrity status as one of the most vicious meat-eating dinosaurs ever. It was only with the release of the movie Jurassic Park in 1993 that a hitherto little-known carnivore named Velociraptor seized the spotlight and pushed Deinonychus forcefully into the rear. “Velociraptor had been discovered in the Gobi Desert of Mongolia during the 1920s. However not much was known about it since only partial remains had been found. What was certain was that the real-life Velociraptor was nowhere near as big as the creatures portrayed in the movie, measuring just 2 feet tall and 6 feet long, and scarcely weighing 30 pounds. Ever since its discovery, Velociraptor had been a somewhat obscure meat-eating dinosaur which not many people knew about, but all that changed with Jurassic Park. “In fact Michael Crichton, the author of the Jurassic Park novel which was published in 1990, based his raptors on the wolf-sized Deinonychus of Montana, not the small turkey-sized Velociraptor of Mongolia. Crichton followed a school-of-thought which had gained traction during the 1980s which stated that Deinonychus was a larger North American species of Velociraptor. If you look at Gregory Paul’s artwork during that time, you’ll see that he often illustrates his Deinonychus with an elongated concave Velociraptor-like skull rather than the high triangular skull that is typically shown in Deinonychus restorations. In both the 1990 book Jurassic Park and the 1993 movie adaptation, the paleontologist Dr. Alan Grant and his dig team were excavating Velociraptor bones in the badlands of Montana instead of in the Gobi Desert – they were actually digging up Deinonychus bones, and the raptors hunting Lex and Tim in the kitchen were supposed to be Deinonychus as well. Another reason why Michael Crichton made the change from Deinonychus to Velociraptor in his book was because he thought that Velociraptor was a cooler-sounding name. Since the movie Jurassic Park debuted in 1993, Velociraptor has been regarded as the quintessential ‘raptor’. Its name became a household word, and Deinonychus was regrettably cast aside” (https://dinosaursandbarbarians.com/2021/07/24/deinonychus-the-dinosaur-that-changed-the-world/). “Ostrom (1928-2005) was raised in Schenectady, N.Y., where he later attended Union College, intending to follow his father into medicine. However, upon reading the work of American paleontologist George Gaylord Simpson and initiating a correspondence with him, he instead decided to pursue his interest in evolution. After earning a bachelor’s degree (1951) in geology and biology, Ostrom enrolled at Columbia University, New York, having served as Simpson’s field assistant the previous summer. He was a research assistant at the American Museum of Natural History (1951–56) and taught at Brooklyn College in New York (1955–56) and Beloit College in Wisconsin (1956–61). After receiving a doctorate in vertebrate paleontology (1961) from Columbia, he was hired as an assistant professor of geology at Yale University (1961) and assistant curator of vertebrate paleontology at Yale’s Peabody Museum of Natural History (1961). He was made full professor and curator in 1971” (Britannica). In 2019, a 50th anniversary edition of Ostrom’s monograph was published by Yale University Press. Ashworth, Paper dinosaurs 1824-1969, Linda Hall Library Exhibition, 1996 (https://dino.lindahall.org/index.shtml). Conniff, ‘The man who saved the dinosaurs,’ Yale Alumni Magazine 77, July/August 2014 (https://yalealumnimagazine.com/articles/3921-the-man-who-saved-the-dinosaurs). Dodson & Gingerich, ‘John H. Ostrom’, American Journal of Science 306 (2006), pp. i-vi.

Large 8vo (251 x 174mm), pp. [viii], 165, with frontispiece drawing of Deinonychus by Robert Bakker. Original printed wrappers (slightly rubbed).

Item #5493

Price: $3,500.00