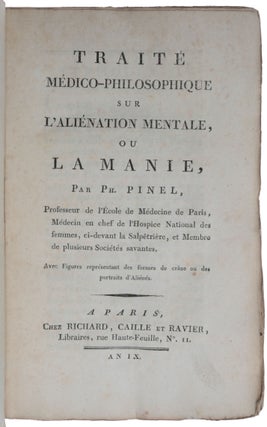

Traité medico-philosophique sur l’aliénation mentale, ou la manie.

Paris: Chez Richard, Caille et Ravier, An IX [1801]. First edition of a landmark work on the treatment of the insane and mentally ill. It presented the textual foundation of psychiatry, stands as the first great publication of the nineteenth century in clinical medicine, and at the same time as one of the paradigmatic expressions of the medical and scientific revolution that was taking place in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. In 1793 Pinel, newly appointed physician at the Bicêtre Hospital, the Paris asylum for men, ordered the chains and shackles removed from 49 patients (an event commemorated at the time in paintings and popular prints) in order to try his new, more humane methods of treatment. He did the same for the female inmates of Salpêtrière when he became the director there in 1794. “Pinel’s psychiatric work effectively transformed the prison for the insane into a hospital. He did not merely initiate better treatment for the mentally ill, however, but rather concerned himself with establishing psychiatry as a discrete branch of medicine … Pinel’s classification of mental diseases retained the old divisions of such illnesses as manic, melancholic, demented, and idiotic. He presented these classes (with a disclaimer—it was necessary to retain them ‘for the time being,’ since medicine was not advanced enough for subtler distinctions) as late as 1812. He nevertheless made finer distinctions, isolating mania from delirium, and pointing out that in this state the intellectual functions might be intact, and, in his description of idiocy, citing stupor, the first stage of some types of mental disease. Pinel recognized the relationship between periodic mania and melancholy and hypochondria and stressed the danger of suicide by the melancholic patient. He also mentioned the possibility of altruistic homicide. In establishing the cause of mental illness, Pinel was wary of ‘metaphysical discussions or certain ideological ramblings,’ and he categorically rejected the notion of demonic possession or sorcery. Faithful to the doctrines of Locke and Condillac, he considered emotional disorders to be the primary factor in precipitating intellectual dysfunctions; he also took into account heredity, morbid predisposition, and what he called individual sensitivity. Pinel’s psychiatric therapeutics, his ‘traitement morale,’ represented the first attempt at individual psychotherapy. His treatment was marked by gentleness, understanding, and goodwill. He was opposed to violent methods—although he did not hesitate to employ the straitjacket or force-feeding when necessary. He recommended close medical attendance during convalescence, and he emphasized the need of hygiene, physical exercise, and a program of purposeful work for the patient. A number of Pinel’s therapeutic procedures, including ergotherapy and the placement of the patient in a family group, anticipate modern psychiatric care” (DSB). “Pinel was among the first to treat the insane humanely; he dispensed with chains and placed his patients under the care of specially selected physicians” (Garrison-Morton). “Pinel was born in the rolling hills of Jonquières, France. He was the son and nephew of physicians. After receiving a degree from the faculty of medicine in Toulouse, he studied an additional four years at the Faculty of Medicine of Montpellier. He arrived in Paris in 1778. Pinel did much to establish psychiatry formally as a separate branch of medicine. He made notable contributions to the classification of mental disorders and has been described by some as ‘the father of modern psychiatry’. Pinel was also one of the first clinician who believed that medical truth was derived from clinical experience. Pinel considered migrating to America. In 1784 he became editor of the not very prestigious medical journal the Gazette de santé, a four-page weekly. He was also known among natural scientists as a regular contributor to the Journal de physique. He studied mathematics, translated medical works into French, and undertook botanical expeditions. “At about this time he began to develop an intense interest in the study of mental illness. The incentive was a personal one. A friend had developed a ‘nervous melancholy’ that had ‘degenerated into mania’ and resulted in suicide. What Pinel regarded as an unnecessary tragedy due to gross mismanagement seems to have haunted him. It led him to seek employment at one of the best-known private sanatoria for the treatment of insanity in Paris. He remained there for five years prior to the Revolution, gathering observations on insanity and beginning to formulate “Pinel rejected the prevailing popular notion that mental illness was caused by demonic possession. He stated that mental disorders could be caused by a variety of factors including psychological or social stress, congenital conditions, or physiological injury, psychological damage, physical conditions and heredity. He observed and documented the subtleties and nuances of human experience and emotion. He identified predisposing psychosocial factors of mental ill such as an unhappy love affair, domestic grief, devotion to a cause carried to the point of fanaticism, religious fears, the events of the revolution, violent and unhappy passions, exalted ambitions of glory, financial reverses, religious ecstasy, and outbursts of patriotic fervor. He noted that a state of love could turn to fury and desperation, can cause mania or 'mental alienation'. He also spoke of avarice, pride, friendship, bigotry and vanity. “Pinel proposed a new, nonviolent approach to the care of mental patients came to be called moral treatment, in the sense of social and psychological factors. He strongly argued for the humane treatment of mental patients, including a friendly interaction between doctor and patient. His treatment was marked by gentleness, understanding, and goodwill. He was opposed to violent methods – although he did not hesitate to employ the straitjacket or force-feeding when necessary. Pinel expressed warm feelings and respect for his patients: ‘I cannot but give enthusiastic witness to their moral qualities. Never, except in romances, have I seen spouses more worthy to be cherished, more tender fathers, passionate lovers, purer or more magnanimous patriots, than I have seen in hospitals for the insane’. “Pinel visited each patient, often several times a day. He engaged them in lengthy conversations and took careful notes. He recommended close medical attendance during convalescence, and he emphasized the need of hygiene, physical exercise, and a program of purposeful productive work for mental patients. He further contributed to the development of psychiatry through his establishment of the practice of maintenance and preservation of detailed case histories for the purpose of treatment and research. Pinel also made the introduction of hospital treatment, doctor’s rounds, medical procedures, unchained the insane. Pinel petitioned to the Revolutionary Committee for permission to remove the chains from some of the patients as an experiment, and to allow them to exercise in the open air. When these steps proved to be effective, he was able to change the conditions at the hospital and discontinue the customary methods of treatment, which included bloodletting, purging, and physical abuse. In 1798 Philippe Pinel cut chains from the limbs of patients called ‘madmen’ at the Bicêtre Hospital, a Parisian insane asylum emphasized the need of hygiene, physical exercise, and a program of purposeful productive work … “Soon after his appointment to Hôspital Bicêtre, Pinel became interested in the seventh ward where 200 mentally ill men were housed. He asked for a report on these inmates. A few days later, he received a table with comments from the ‘governor’ Jean-Baptiste Pussin (1745-1811). In the 1770s Pussin had been successfully treated for scrofula at Bicêtre; and, following a familiar pattern, he was eventually recruited, along with his wife, Marguerite Jubline, on to the staff of the hospice. While at Bicêtre, Pinel did away with bleeding, purging, and blistering in favor of a therapy that involved close contact with and careful observation of patients. Pinel visited each patient, often several times a day, and took careful notes over two years. He engaged them in lengthy conversations. His objective was to assemble a detailed case history and a natural history of the patient’s illness. “In 1795, Pinel became chief physician of the Hospice de la Salpêtrière, a post that he retained for the rest of his life. The Salpêtrière was, at the time, like a large village, with seven thousand elderly indigent and ailing women, an entrenched bureaucracy, a teeming market and huge infirmaries. Pinel missed Pussin and in 1802 secured his transfer to the Salpêtrière. It has also been noted that a Catholic nursing order actually undertook most of the day-to-day care and understanding of the patients at Salpêtrière, and there were sometimes power struggles between Pinel and the nurses. Pinel created an inoculation clinic in his service at the Salpêtrière in 1799, and the first vaccination in Paris was given there in April 1800. “In 1794 Pinel made public his essay ‘Memoir on Madness’, recently called a fundamental text of modern psychiatry. In 1798 Pinel published an authoritative classification of diseases in his Nosographie philosophique ou méthode de l'analyse appliquée à la médecine. Pinel’s classification of mental disorder simplified Cullen’s ‘neuroses’ down to four basic types of mental disorder: melancholia, mania (insanity), dementia, and idiotism. Later editions added forms of ‘partial insanity’ where only that of feelings which seem to be affected rather than reasoning ability. In his book Traité médico-hilosophique sur l'aliénation mentale; ou la manie, published in 1801, Pinel discusses his psychologically oriented approach. “The central and ubiquitous theme of Pinel's approach to etiology (causation) and treatment was ‘moral,’ meaning the emotional or the psychological not ethical. He observed and documented the subtleties and nuances of human experience and behavior, conceiving of people as social animals with imagination. Pinel noted, for example, that: ‘being held in esteem, having honor, dignity, wealth, fame, which though they may be factitious, always distressing and rarely fully satisfied, often give way to the overturning of reason’. He spoke of avarice, pride, friendship, bigotry, the desire for reputation, for conquest, and vanity. He noted that a state of love could turn to fury and desperation, and that sudden severe reversals in life, such as ‘from the pleasure of success to an overwhelming idea of failure, from a dignified state – or the belief that one occupies one – to a state of disgrace and being forgotten’ can cause mania or ‘mental alienation’. He identified other predisposing psychosocial factors such as an unhappy love affair, domestic grief, devotion to a cause carried to the point of fanaticism, religious fears, the events of the revolution, violent and unhappy passions, exalted ambitions of glory, financial reverses, religious ecstasy, and outbursts of patriotic fervor” (Sushma et al.). En français dans le texte 203; Garrison-Morton 4922; Grolier Medicine 54; Heirs of Hippocrates 1070; Hunter & Macalpine, pp. 602-610; Waller 7456; Wellcome IV, p. 388; Norman 1701. Sushma, Meghamala & Tavaragi, ‘Moral treatment: Philippe Pinel,’ International Journal of Indian Psychology 3 (2016), pp. 165-170.

his views on its nature and treatment. Pinel was an Ideologue, a disciple of the abbé de Condillac. He was also a clinician who believed that medical truth was derived from clinical experience. Hippocrates was his model. During the 1780s, Pinel was invited to join the salon of Madame Helvétius. He was in sympathy with the French Revolution. After the revolution, friends he had met at Madame Helvétius' salon came to power. In August 1793 Pinel was appointed ‘physician of the infirmaries’ at Bicêtre Hospital. At the time it housed about four thousand imprisoned men-criminals, petty offenders, syphilitics, pensioners and about two hundred mental patients. Pinel’s patrons hoped that his appointment would lead to therapeutic initiatives.

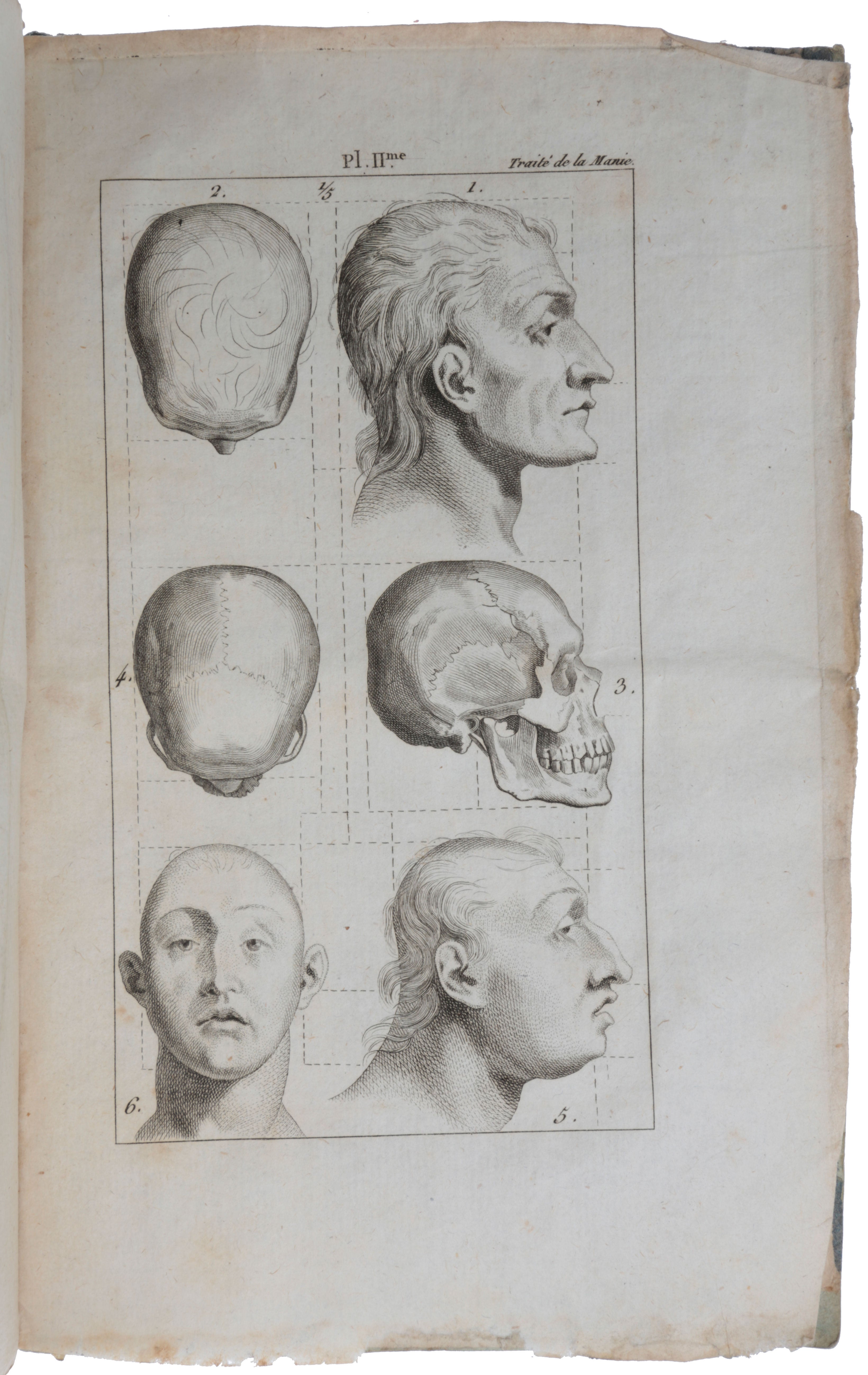

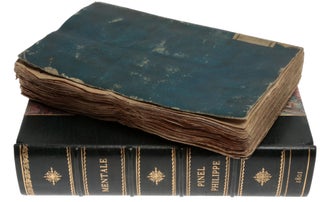

8vo (213 x 135mm), pp. [i-v], vi-lvi, 318, with printed folding table and two engraved plates. Uncut in original blue interim boards. A fine copy.

Item #5631

Price: $6,800.00