Recherches sur les causes des principaux faits physiques.

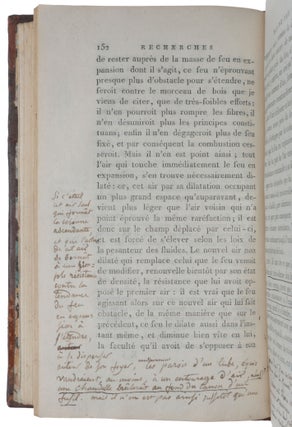

Paris: Maradan, Seconde Année de la République, [1794]. First edition of the first of Lamarck’s full-length treatise on chemistry, a copy with extensive near-contemporary annotations. “With the publication of the Recherches, Larmarck brought together the various strands of his work in physics and chemistry, and his views on the differences between organic and inorganic beings” (Corsi, The Age of Lamarck, pp. 47-48). “In this work Lamarck sets forth his views on the immutability of species and attacks the theory of the spontaneous origin of life. The book is interesting in the history of chemistry, because Lamarck attacks Lavoisier’s anti-phlogistic theory” (Duveen). Although Lamarck’s chemical theories are often dismissed because of his continued belief in the four elements, they are of interest because of their central importance in the later development of his theory of evolution. His view of the natural evolution of chemical compounds paralleled his theory of the evolution of living species, but in reverse: in his view only living beings could produce chemical compounds, an aberration from the natural tendency of inorganic matter to gradually decompose into its constituent elements, in the process producing all known inorganic substances. This mineral hierarchy of being had in common with Lamarck’s theory of species evolution an emphasis on the “gradual and successive production of forms, while denying the relevance of defined species” (Norman). Lamarck “assumed as elements a vitrifiable earth, water, air, fire, and light, which have no attraction for one another but tend to separate unless constrained by force; he developed his views in great detail; coal-fire is the radical of all combustibles and on combustion separates as heat-fire. He proposed a new ‘pyrotic theory’” (Partington, III, p. 390). “Lamarck's chemical theories are usually dismissed as the product of unfortunate speculation because they represented the ‘old chemistry’ overturned by Antoine Laurent Lavoisier and the ‘chemical revolution.’ However, they provide the key to his conception of nature and are essential features of his theory of evolution. Lamarck began his work in chemistry in the 1770s, when the four-element theory of matter (earth, air, fire, water) was still generally accepted in France. The fact that the most important element in his system was fire in its various states of modification allowed Lamarck to explain most of the known chemical and physical phenomena. His chemistry was also used to explain the mechanical interaction of individuals with the environment and, thus, evolution and the emergence of higher mental faculties” (DSB). “Lamarck’s first scientific synthesis, the Recherches of 1794, was not primarily concerned with biological questions, although discussions on the differences between organized and mineral bodies, and between plants and animals featured prominently. The nucleus of the work was the presentation of the author’s chemical and physical theories. Fire was the central element in Lamarckian chemistry, as evidenced by the long chapter devoted to it in the first volume. Lamarck admitted that ‘the pneumatic theory has won approval from a majority of the best known chemists’. To avoid appearing to be a supporter of outdated theories, the author added the following note: ‘Moreover, I guarantee that [my theory] is not at all the phlogiston theory, which I do not accept in the form in which it has been presented.’ “Readers had no trouble understanding that the author was a declared opponent of the new chemistry, to which he replied with a rather sophisticated revision of the classical theory of the four elements – fire, air, earth and water. Lamarck was willing to admit that the new chemical discoveries and experiments had contributed significantly to the development of the discipline. In his view, however, it was undeniable that chemistry had advanced without taking the other branches of natural science into account. He utterly disagreed with the advocates of extreme specialization and of the reciprocal independence of histoire-naturelle disciplines. Such scientists, he claimed, were bound to overlook principles and facts attested to other disciplines. They would build ad hoc hypotheses to explain new observations affected within the scope of the specific research sector. Lamarck’s basic argument against the new chemists was that they had needlessly multiply the number of chemical elements. Ever since the study of gases had flourished and methods of chemical analysis had been successfully improved, naturalists had taken to regarding the basic ingredients of compounds as elements that could not be further decomposed. As a result, the principles of chemistry were daily becoming more complicated, less clear, and far less general. If every discipline were to develop along the same lines, Lamarck noted, naturalists could soon have to relinquish all hope of understanding the laws and basic principles of natural processes. “Lamarck set out to demonstrate that recent developments in chemistry and mineralogy could be fitted into a unitary interpretation of nature. The author modestly announced that he had a few ‘discoveries’ to announce and that he owed much to his colleagues’ observations. What he did claim credit for was the construction of a coherent system of ‘closely related principles’ capable of explaining the laws and general principles of physical and chemical phenomena, ‘but also of the main organic facts, which it is so important to know in depth … these principles lead us to the true cause of our organs’ development and of the growth of our body’s parts, and to the very cause that puts an end to these and necessarily terminates out lives.’ “Chemistry was the undisputed keystone of the entire Lamarckian system. The author recognized the existence of only four elements, each possessing a tendency to remain in, or return to, a pure state. Thus, contrary to the assertions of many contemporary authors, chemical compounds and minerals could not form naturally through affinity principles or crystallization but were all generated by the action of organic beings. The tendency of elements to return to their natural state caused the gradual degeneration and decay of organic remains and the compounds derived from them. This process accounted for the immense variety of observed mineral forms. There was a major difference, however, between plant action and animal action in forming compounds. Plants could directly combine the four elements and turn them into the compounds needed for life and for plant growth. Animals absorbed through nutrition the compounds already developed by plants and produced even more complex ones. “Lamarck devoted a long chapter of the second volume to ‘organized beings’ (pp. 184-270), which played a most important part in nature and its chemistry. While the activity of organisms explained the origin of compounds and minerals, it was definitely impossible to determine the origin of organized beings. The life essence of organized beings was ‘a principle for ever beyond man’s ken’, ‘a vital principle or movement that endows [them] with the capacity to develop, to grow up to a certain point, and lastly to reproduce beings similar [to themselves] through the organs designed for fertilization.’ Everything in nature tended to disintegration, to the reduction of matter to an elemental state. Minerals gradually turned one into another, forming an immense series of decompositions determined by the infinite combinations of situations in which organic remains could be found. Minerals could not reproduce themselves (this ruled out the notion of mineral species) and were subject to all manner of external influences. Organisms, in contrast, could reproduce entities similar to themselves and underwent only slight environment-induced variations. Regarding their specific characters, organisms were immune to outside agents. “The difference between minerals and organic beans was truly ‘infinite.’ Lamarck argued the extreme thesis that organized bodies ‘are astonishing beings that in no way belong to nature. All that can be referred to as ‘nature’ is incapable of giving life … All of nature’s powers combined with all possible circumstances … cannot produce a being endowed with organic movement capable of reproducing itself and subject to death.’ “Not only is the principle of life unknowable and different from nature but the total opposition between life and nature ruled out the spontaneous generation of organic beings. “For Lamarck, it was relatively easier to explain the death of organisms and to show how his chemistry could account for processes peculiar to living organisms. The life principle was indispensable for engendering organisms and keeping them alive. It acted through an organic movement of material elements and the intake of compounds from the environment through nutrition. The laws of physics and chemistry could therefore be applied to investigate the operations characteristic of vital phenomena. Organic life was seen as a state of equilibrium between the organizing force of the life principle and the tendency to decomposition. The latter was inherent in the organisms material elements and in the parts absorbed through nutrition. In a young organism’s fibres, elastic principles outnumbered and prevailed over ‘fixed and earthy principles.’ “Organic movement thus encountered few obstacles, and life functions were distinctly vigorous. Fibre elasticity and the energy of organic movement explained the rapid growth of the individual. This process inevitably entailed the absorption of compounds and the production of even more complex ones inside the organism. Excretions notwithstanding, the ‘earthy’ parts that were absorbed made the organism’s fibres less elastic and slowed organic movement, leaving an ever-wider place for nations disaggregative tendency to operate. Once the equilibrium threshold between the two principles have been crossed, the body fibres inexorably happened and the organism was due to die. “Lamarck’s approach to the study of natural reality, the mineral kingdom and ‘organised bodies’ was based on the refusal of all historico-genetic considerations. The only genetic aspect he recognized was this excessive production of minerals from animal and plant remains. The processes obviously implied a history in the sense that all mineral forms deteriorated over time. But Lamarck explicitly rejected any connection between his mineral formation doctrine and earth history … The rejection of the historico-genetic approach also masked a problem of internal coherence in the Lamarckian system. The author realized that the synthesis set out in his work left unresolved a rather embarrassing question, to which he was unwilling or unable to reply. If it were true that only organized beings could assemble combinations of the prime elements and produce the minerals that existed in nature, it was legitimate ask how and on what the first living beings – whether plants or animals – had lived … “Many historians have rightly emphasized the importance of the most physical chemical and mechanical ideas in the development of his biological concepts … It has even been argued that Lamarck’s mineral-formation theory may have supplied a key element for the conceptual framework of his transformism. The genesis of minerals was governed by a general law of degeneration, whose applications were in turn conditioned by the set of environmental circumstances in which individual mineral-formation processes occurred. This style of explanation is indeed reminiscent of the dialectical relationship between the pattern of growing organic complexity and the influence of circumstances – a relationship that was to characterize Lamarck’s transformist theory” (Corsi, pp. 48-53). The annotator’s comments show a fairly advanced and up-to-date scientific knowledge. His references to scientific authorities cover a wide spectrum, from ancient authors such as Descartes (whose ‘dust theory’ he virulently criticizes), Newton, Leibniz, Franklin, but also theorists who became known at the beginning of the 19th century such as the physicist Antoine Libes and the philosopher Pierre-Hyacinthe Azaïs. The annotations were probably made between the end of the First Empire (1810-1815) and the end of 1829.

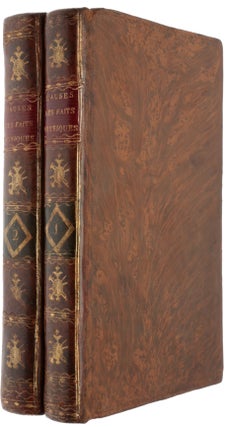

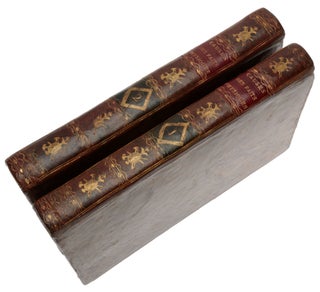

Two vols., 8vo (197 x 122 mm), pp. xvi, 375, [1 blank], with engraved plate by Bovinet after Marechal; [iv], 412, with folding letterpress table. Contemporary calf, richly golt spines, some very well done restoration to spines.

Item #5660

Price: $4,500.00