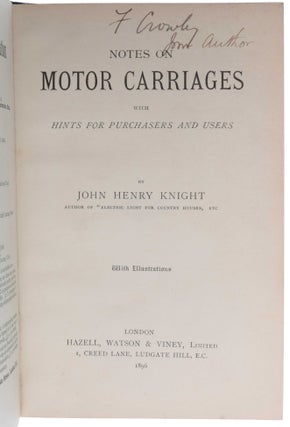

Notes on Motor Carriages with Hints for Purchasers and Users.

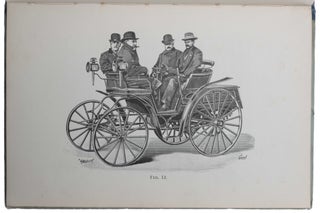

London: Hazell, Watson and Viney, 1896. First edition, inscribed presentation copy, of this scarce early study on automobiles by the inventor and engineer John Henry Knight. “The development of the automobile is of great historic importance in the history of technology. Of all the early works written on the subject, this book by Knight had a great impact on both the makers and the users of automobiles” (Dibner online). “There were many who attempted to apply the power of small gasoline, gas-generator or electric battery propulsion to a carriage and to make an automobile. The release of the Otto 4-cycle engine patent from monopoly control in 1885 multiplied these efforts and many ‘horseless carriages’ took to the roads of America and Europe. Prominent names among the more successful pioneers in this effort are Daimler, Benz, Peugeot, Duryea and Mueller. It was in the methods of automobile manufacture and the approach to the mass market that the 20th century inventors and industrialists developed new sociological concepts of great and lasting importance” (Dibner, 25th Anniversary Edition). This book was written soon after Knight’s construction of one of Britain’s first petrol-powered motor vehicles. The book includes chapters on several famous makes of cars, including Benz, Decauville, Motor Mfg. Co., New Orleans, Argyll & De Dion Voiturette, Serpollet, and Stanley Steam Car. There are also discussions on motor bicycles and tricycles such as Singer, Minerva, etc. The author counselled prospective buyers “to see the machine taken to pieces and put together again before purchasing.” Knight also documented some of the earliest motor-sport events, including the 1894 Paris-Rouen and 1895 Paris-Bordeaux-Paris races. “John Henry Knight (1847-1917), from Farnham, Surrey, UK, was a wealthy engineer, landowner and inventor. With the help of the engineer George Parfitt he built one of Britain’s first petrol-powered motor vehicles … On 17 October 1895, with his assistant James Pullinger, they drove through Farnham, Surrey, whereupon he was prosecuted for using a locomotive with neither a licence nor a man walking in front with a red flag … Knight was a founder member of the Automobile Association and politically active in the repeal of the Red Flag Act” (Wikipedia). ABPC/RBH list four copies in the last 45 years, but no presentation copies. Provenance: F. Crowley (?) (author’s presentation inscription on title). “John Henry Knight was born in 1847 to John Knight, a banker and brewer of Farnham, who died in 1856 when John Henry was 9 years old. His mother was Mary Knight. His father’s will bequeathed him title to, among other things, ‘The Anchor Inn, Normandy’ when he was 21 years old. He was born and raised at Weybourne House, Weybourne, Farnham, Surrey, which still stands today. He then moved to Barfield in Runfold, just outside Farnham, which is now a Preparatory school (whose alumni include Mike Hawthorn). “He was inspired by The Great Exhibition of 1851 and went on to train as an engineer, developing an early enthusiasm for steam powered road-going transport. He owned an engineering works on West Street, Farnham. “In 1895 Knight built one of Britain's first petrol-powered motor vehicles, a three-wheeled, two-seater contraption with a top speed of only 8 mph (13 km/h). It was ‘The first petroleum carriage for two people made in England’ and believed to be the fourth British vehicle to be built plus the ‘first petrol driven vehicle ever to be driven on British roads.’ Known as the Trusty, it had a single cylinder Trusty 1,565cc engine. The car was designed very much as an experiment in order to attract police attention and therefore create public awareness of the many restrictions which prevented the use of motor carriages in Britain at that time. Knight managed to use the vehicle for some 150 miles (240 km) on public roads, before being stopped by the Police. “On 17 October 1895 Knight’s assistant, James Pullinger, was stopped in Castle Street, Farnham, by the Superintendent of Police and a crowd had gathered by the time Knight arrived. The Superintendent asked whether it was a steam engine, Knight replied that it was not and thus admitted liability. He and Pullinger were charged with using a locomotive without a licence. The case was heard at ‘Farnham Petty Sessions’ held at Farnham Town Hall on 31 October 1895. Knight and Pullinger were both fined half a crown – 2s 6d (or possibly 5 shillings) – plus 10 shillings costs (or possibly 12s 6d). Knight was restricted to using the car only on farm roads until the Locomotive Act was replaced by the Locomotives on the Highway Act, on 14 November 1896. His action was later also responsible for the repeal of the notorious Red Flag legislation. “Knight’s vehicle was said to be ‘almost silent’ when it was running; the vehicle entered a limited production run in 1896 and shortly after that the tricycle was the only British car at the 1896 Horseless Carriage display at Crystal Palace, although the design was later changed in favour of a four-wheel version. The car is currently on display at the National Motor Museum. “Knight was a founder member of the Automobile Club of Great Britain, so the members first ever ‘club run’ was hosted at his Barfield home. “Although best remembered for his car and his driving, he had, for many years, been an inventor and a designer of steam-powered machines, which he used for agricultural work and early road transport. In 1868 he built a steam powered road vehicle, although it was not a practical proposition due to inefficiency” (Wikipedia). Knight also includes in his book an account of two early motor races. The question of what was the first motor-sport event is a matter of dispute. Some give the honour to the 1894 Paris – Rouen ‘Concours des Voitures sans Chevaux’, although that was not strictly speaking a race, the prizes being awarded by a panel of judges who allocated the rewards based on their interpretation of which vehicle completed the course safely and economically (see pp. 60-62 for Knight’s account of this ‘race’). The 1895 Paris – Bordeaux – Paris race, on the other hand, was indisputably a race. Knight tells the story (pp. 62-67): ‘The June race, Paris to Bordeaux and back, of last year (1895) was on different lines. Instead of being organised by the proprietors of a newspaper, it was originated and carried out by well-known men in sport and commerce … Sixty-nine thousand one hundred francs was subscribed for prizes. The course was from Paris to Bordeaux and back, a distance of about seven hundred and forty-four English miles. After deducting five thousand francs for expenses the prizes would be as follows: The first arrival in Paris, 50 per cent; the second arrival in Paris, 20 per cent; the third arrival in Paris, 10 per cent; the four following, 5 per cent. But the first prize could only be taken by a carriage containing four people. An entrance fee of two hundred francs was paid by the owner of each vehicle. ‘The steersman and driver might be changed during the contest. Any manufacturer might enter any number of carriages, provided they were of different types and dimensions. Instead of the full number of passengers, the vehicles might carry seventy-five kilogrammes of ballast for each vacant place. No repairs were allowed to be done, except by those in the charge of the carriage, and with tools carried with them … Maps of the course were provided for the competitors. Direction posts were placed at turnings, and flags, or at night signal lamps, were placed at descents that might be deemed dangerous; flags and lights were also placed at some short distance from the railways which were crossed on the level … “The Dion-Bouton and the Serpollet carriages had to abandon the course, as did also the electric carriage of M. Jeantard. This was worked by accumulators, and a special train was chartered to convey the charged accumulators to various points on the route. The only steam carriage which went the whole distance was M. Bollee’s, a steam omnibus which had been in use for nine or ten years; and to him a supplementary prize was awarded. The first, third and fourth prizes were awarded to MM. Peugeot; the second and fifth to MM. Panhard and Levassor; the sixth and seventh to M. Roger” (The Motor Miscellany, The Dawn of Motor Racing). Dibner 184.

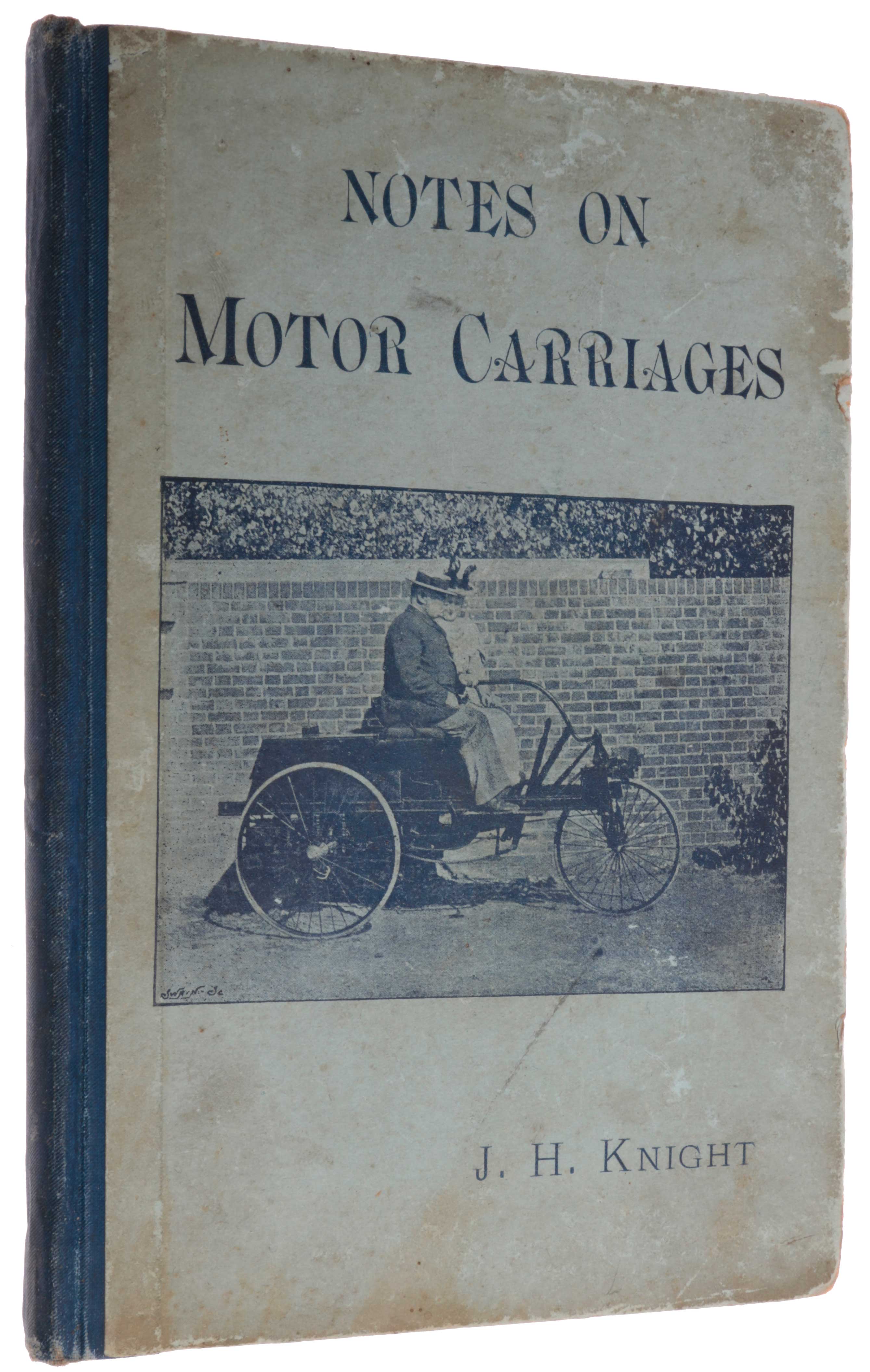

8vo (182 x 120 mm), pp. [ii], 84, [2], illustrated throughout with numerous in-text vignettes and full-page illustrations, advertising matter on the first and last leaves. Original publisher’s cloth-backed boards, with photograph of Knight driving his two-person vehicle on front board. (rubbed and soiled).

Item #5679

Price: $3,500.00