Clinique chirurgicale, exercée particulierement dans les camps et les hopitaux militaires, depuis 1702 jusqu’en 1829.

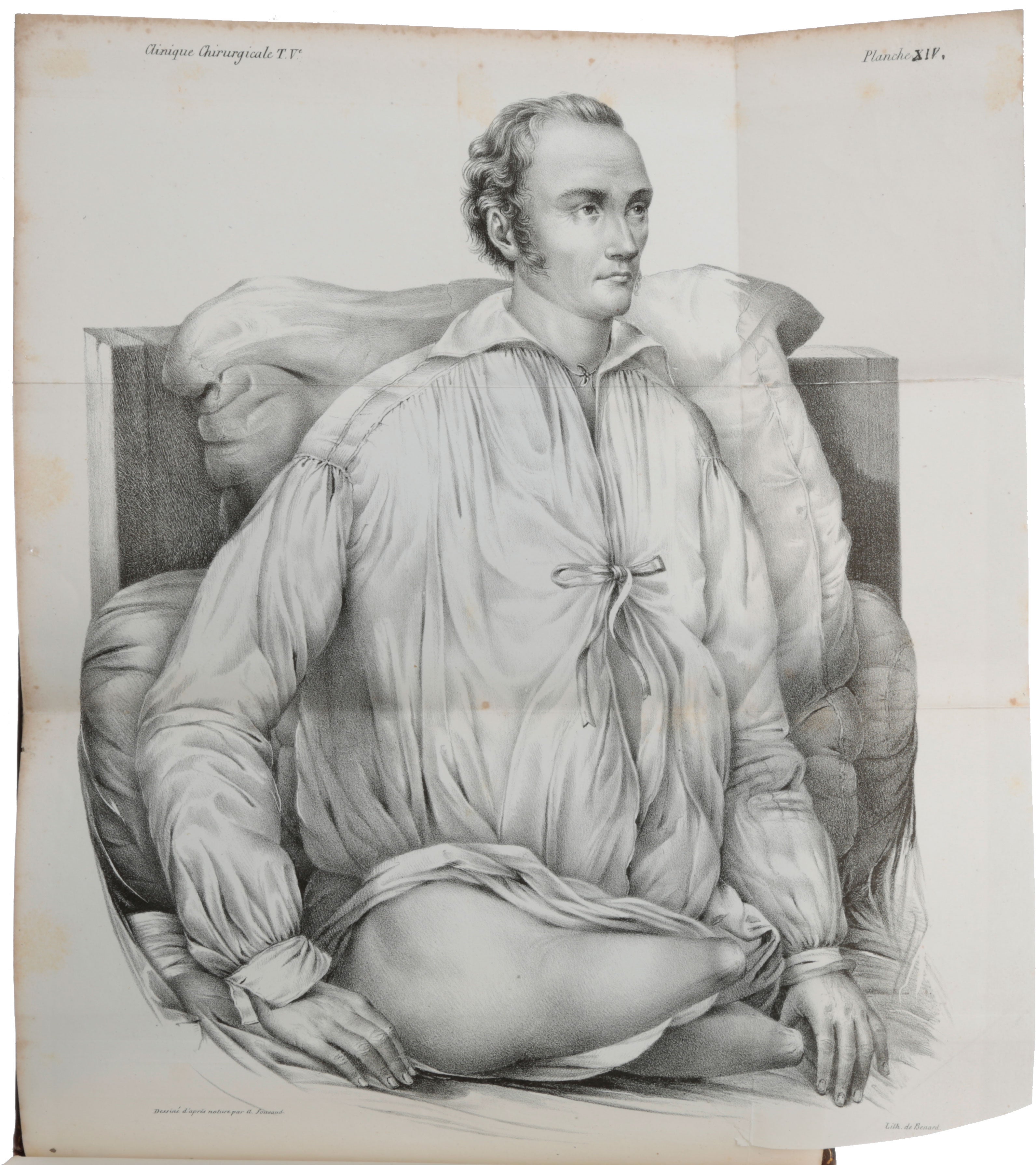

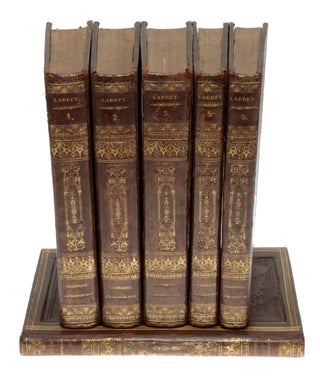

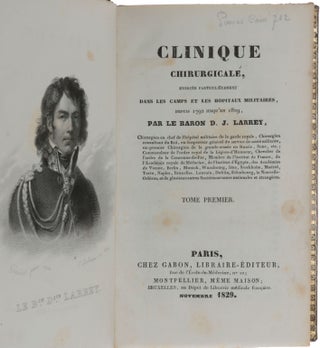

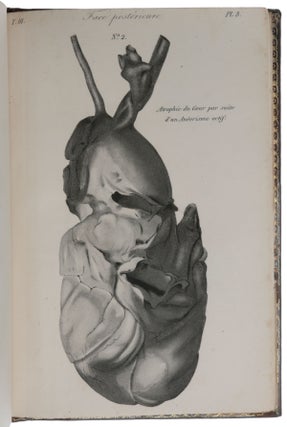

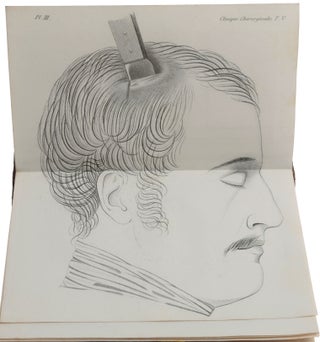

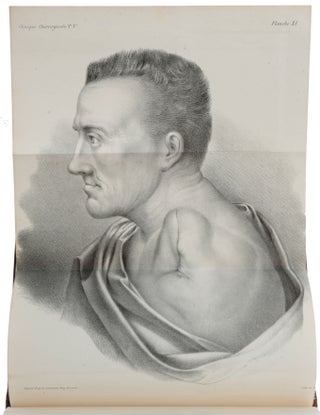

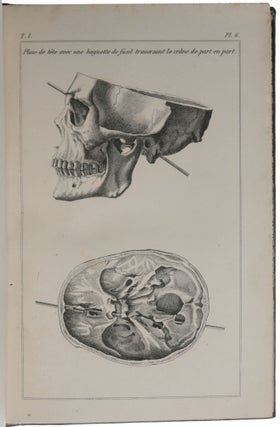

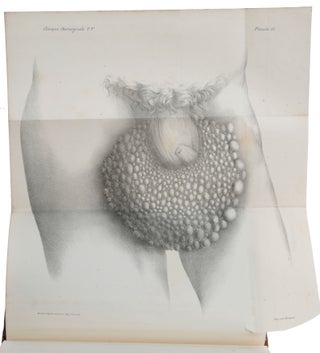

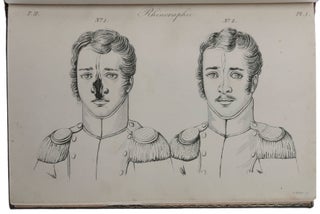

Paris: Gabon, November 1829 (vols. 1-3 and atlas); J.-B. Balliere, 1832 (vol. 4); J.-B. Balliere, 1836 (vol. 5 and atlas), 1829-1836. First edition, extremely rare when complete with all five text volumes and their two atlases, and in superb uniform contemporary bindings, of “Larrey’s longest surgical treatise, and the only one that is extensively illustrated. Most of the illustrations concern surgical pathology. The work was published over seven years, and is very rarely found complete” (Norman). Larrey (1766-1842) was the greatest military surgeon in history (Garrison-Morton 2160). He “began his medical studies with his uncle in Toulouse and, in 1787, traveled to North America. Returning to Paris, he continued his studies and during the Revolution, in 1792, was attached to the Army of the North. He eventually became principal surgeon of the French Army and thereafter followed Napoleon Bonaparte in almost all his campaigns—in Egypt, in Italy, in Germany and Austria, in Russia, and, finally, at Waterloo. Napoleon made him baron of the empire. After the fall of Napoleon, Larrey’s medical reputation saved him, and he was named a member of the Académie de Médicine at its founding in 1820. Larrey was the first to note the contagiousness of trachoma (1802) and published the first description of trench foot (1812) … He introduced field hospitals, ambulance service, and first-aid practices to the battlefield” (Britannica). Larrey “is hailed as one of the foremost role models in the history of military surgery. The introduction of the rapid evacuation of the wounded from the battlefield by horse-driven special ‘flying ambulances,’ the practice of sensible triage, together with innovating surgical ideas saved many lives and continues to serve as a guide in emergency medicine. His bravery under fire, the unlimited dedication to the wounded, whether friends or foes, and the courageous ethical conduct in preventing the execution of soldiers alleged of self-mutilation – bravely opposing his raging emperor – brought him immediate fame and long-lasting popularity all around the Western World” (Feinsod et al.). “Baron Domonique Jean Larrey, Napolean's brilliant chief surgeon, is truly the father of modern military medicine. By treating the casualties on the battlefield during the fighting, he revolutionized the role of the forward surgeon. His innovative concepts included attention to the total care of the wounded and the health of the troops between battles. Modern military medicine has added little to these concepts. With a fertile imagination and keen observation of clinical states, he introduced improved surgical techniques in thoracic and general surgery. It may be truthfully said that his contributions to military surgery matched the skills of his distinguished chief, Napoleon” (Brewer, p. 1096). The only other complete copy listed on ABPC/RBH is the Norman copy, which was not uniformly bound. In this copy, the plates of the atlas to vol. 5, which are printed in larger format, are folded and bound with the atlas to vols. 1-3. Provenance: Contemporary manuscript ex-libris ‘Mahieu’ in each volume; signature ‘Pascal Cassé’ on each title; from the library of Jean Blondelet, “certainly the greatest collector of medical books in the 20th century” (Sotheby’s); sold Sotheby’s, 30 October 2017, lot 66, €13,750. “Orphaned at the age of 13, Baron Larrey's education was supervised by his Uncle Alexis Larrey, chief surgeon of St. Joseph de la Grave Hospital in Toulouse, France. His brilliance in the University of Toulouse School of Medicine won for him a medal and the opportunity to further his surgical studies in. Paris. In 1792, when war broke out, he was attached to the Army of the Rhine with the rank of surgeon major. Thereafter Larrey served Napolean in every war, including 25 campaigns and 60 battles. “In 1797 Larrey was authorized by the quartermaster general to build ambulances volantes of two types: two-wheel cars for flat country and those with four wheels for rough terrain. An ambulance (the forward medical unit) consisted of 340 men and three divisions of 113 men each with a chief surgeon, 15 other surgeons, five members of the Quartermaster Corps, a trumpeter to carry the surgical instruments, and a drummer boy in charge of surgical dressings. Their uniforms included a saber for defense, and duties were carefully prescribed. The function of this forward medical unit was to rescue the wounded on the field of battle, render first aid, and then to transport them to the frontline hospital. “The casualties rescued by the flying ambulances were thus assembled with all speed at a central point; the most seriously wounded would be operated on by the surgeon in chief or under his direction by a competent surgeon. Larrey added, "We would always start with the most dangerously wounded without regard to rank or distinction." Larrey introduced perhaps the greatest "modern" advance in military surgery: transport from battlefield to the aid, collecting, and clearing stations and thence to the frontline hospital (field or MASH unit). In the Vietnam War the American casualties were picked up during the actual fighting by medical helicopters, triaged in the air, and flown directly to an appropriate hospital for definitive surgical treatment, all within a maximum of 30 minutes, the quintessance of Larrey's ambulance volante. “Larrey's teachings were slow to be accepted. They were completely ignored by the British in the Crimean War. Pirogoff, a Russian surgeon, attempted to introduce some of Larrey’s organizational concepts to the Russian Army. The U.S. Army had only two ambulances in the Quartermaster Corps at the onset of the Civil War. Dr. William G. Hammond, surgeon general of the Union Army, accepted the expert planning of Dr. Jonathan Letterman in caring for the wounded on the battlefield and their evacuations according to the principles of Larrey. The proper measures were slowly instituted. It was not until the battle of Antietam (1862) in the Civil War that the wounded were removed from the battlefield on the day of fighting. ‘How is the surgeon transported to discover motion returning to the lips and eyelids of a man apparently dead, when he perceives the heart palpitate and respiration restored! It is the rapture of Pygmalion, when he perceives the marble being animated under his fingers! In proportion as the torch of life is returned, I redouble my exertions and the patient is at length placed in a warm bed where he usually remains for some days.’ “Larrey’s detailed description of tetanus would grace any modern medical textbook. He stated that if the wound was on an extremity and if early signs of tetanus were observed, the amputation of the extremity might be lifesaving … “Probably one of the least appreciated but the most important contribution was Baron Larrey’s humanism and empathy in the care of the wounded soldiers. His high moral principles are enunciated again and again in his memoirs. The following direct quotations demand further study. ‘I then attended the Imperial Guard, but according to a rule which I established, dressing those first who are most grievously wounded without regard to rank or distinction. The cold was so intense that the instruments frequently fell from my hands. Fortunately, I enjoyed unusual vigor that was produced by the great interest I felt for so many brave fellows.’ ‘… those dangerously wounded must be attended first entirely without regard to rank or distinction and those less severely wounded must wait until the gravely hurt have been operated and addressed. The slightly wounded can go to the hospital in the first and second line, especially officers because the officers have horses.’ “With the current interest in medical ethics, these principles demand our emulation” (Brewer). “In summing up the achievements of Baron Larrey, we should mention the following: Garrison-Morton 5589.1; Wellcome III, p. 451 (without atlas); Norman 1282. Brewer, ‘Baron Dominique Jean Larrey (1766-1842),’ Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery 92 (1986), pp. 1096-8. DaCosta, ‘Baron Larrey: a sketch,’ pp. 104-157 in: Selections from the Papers and Speeches of John Chalmers DaCosta, 1931. Feinsod, Marom & Blecher, ‘Baron Larrey at the dawn of correlative neuroanatomy,’ European Neurology 2022. doi: 10.1159/000523710.

“Baron Larrey not only developed a practical system for the treatment of the wounded casualties during the battle, but he also introduced an all-encompassing method of military medicine. This included procurement and training of staff surgeons and stockpiling of surgical supplies and food. By stressing sanitation he was in advance of that period of medical practice. Even though microorganisms had not been identified as the cause of infection and disease, he recognized that certain types of inflammation and certain illnesses were spread through contact, and he used isolation methods to combat them. The transport of the wounded from the battlefield to the forward surgical installation, and later to the more permanent hospitals, provided models for future generations of military surgeons.

“According to Da Costa, a total of 24 surgical advances were made by Baron Larrey. The immediate surgical care on the battlefield consisted of the control of hemorrhage, debridement of wounds, and immediate amputation of extremities with badly torn and mangled muscles or compound fractures. Thoracic surgical advances included packing of sucking wounds of the chest, aspiration of pericardial effusion or hemopericardium, and drainage of hemothorax and empyema. He treated asphyxia by blowing air into the nares by means of a bellows.

5 vols. 8vo (202 x 120mm) and atlas vol. large 8co (212 x 144mm). I. pp. [i-iii]-viii, [i]-xix, 1-491. II. [i-iii]-vii, [1]-560. III. [i-v], vi-vii, [1]-671. IV. [iv], [i]-viii, [1]-315, with 4 leaves of tables and two folding plates. V. [viii] (including Errata of the fifth volume), [1]-344. [VI] [ii] (half-title and title), 9, 8, 13, 17 double and folding plates (total 47) (a little browning and foxing). Contemporary calf decorated in gilt and blind, boards with 5 gilt fillets and a large lozenge decorated with foliage surrounding a central medallion, spines richly decorated in gilt with red lettering-pieces and gilt lettering at foot (a few scartches to the boards, one joint split).

Item #5782

Price: $32,500.00