Saggio di osservazioni e d’esperienze sulle principali malattie degli occhi.

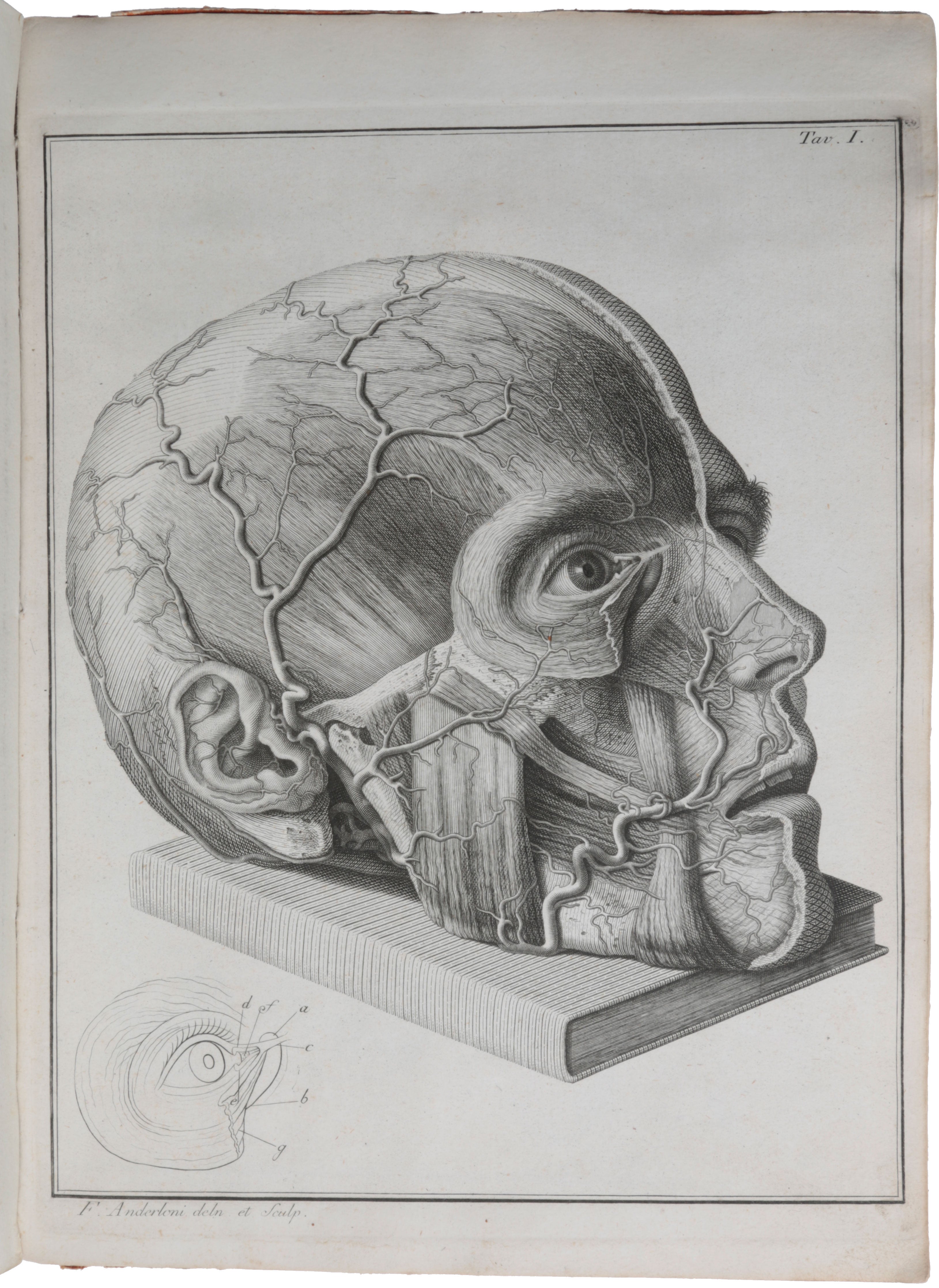

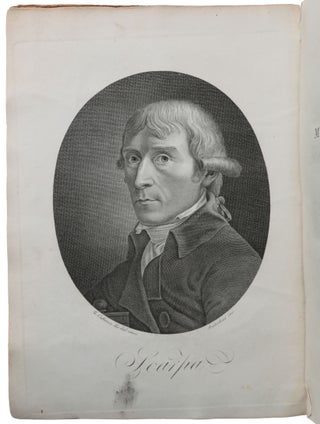

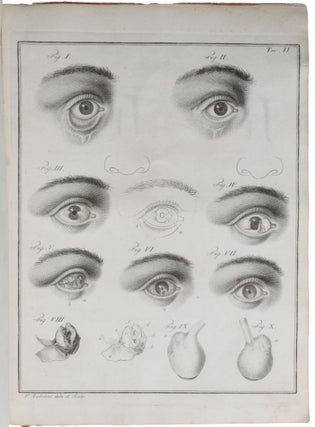

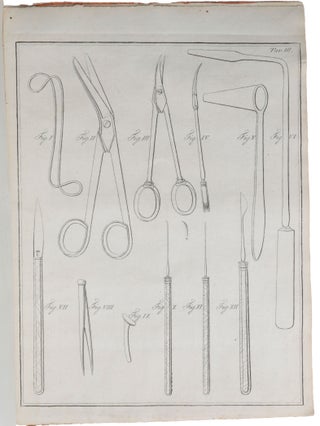

Pavia: Baldassare Comini, 1801. First edition of the first textbook on the diseases of the eye to be published in Italian. “The author has been called the father of Italian ophthalmology” (Garrison-Morton). "In this work Scarpa first described the operation of iridodialysis. The chapters on diseases of the vessels in the eye, on cataract, and on staphyloma are particularly noteworthy. Scarpa’s books were all superbly illustrated with his own drawings and the plates in this work, engraved by Faustino Anderloni, bear witness to Scarpa’s artistic talent. Duke-Elder considered this the greatest work on ophthalmology that had appeared up to its time." Becker Garrison considered Scarpa's illustrations to be the “crown and flower of achievement in anatomic pen-drawing.” Scarpa “himself trained the famous Faustino Anderloni (who become the engraver of his illustrations). The latter's brother, Pietro Anderloni, assisted Faustino in the beginning. His anatomic prints are therefore models of anatomic representation as regards faithful differentiation of the tissues, correctness of form, and the utmost perfection of engraving. They rank with Soemmerring’s illustrations and even surpass them in respect of the vigor of the engravings” (Choulant, p. 298). “This classic work on ophthalmology remained the standard text for several decades, going through several editions and translations. It established Scarpa’s reputation as a leading ophthalmologist and is especially notable for its copperplate engravings of the anatomy of the eye, drawn by the anatomist” (Heirs of Hippocrates). Antonio Scarpa studied at the University of Padua, where he served as assistant and personal secretary to Morgagni, the master of pathological anatomy. After ten years as professor of anatomy and clinical surgery at the University of Modena, Scarpa joined the medical faculty at Pavia and served as chair of anatomy for the rest of his professional life. Scarpa wrote important works in otolaryngology, orthopedics, ophthalmology, neuroanatomy, and general surgery. He was the first to demonstrate cardiac innervation and to accurately describe the pathological anatomy of congenital club-foot. He also introduced the concept of arteriosclerosis, identified ‘Scarpa's triangle’ of the thigh, and provided the first detailed description of sliding hernia of the large bowel. Provenance: Gaetano Tamanti (?) (signature on title). “Antonio Scarpa (1747-1832) was not an ophthalmologist, yet he wrote a hugely influential textbook on ophthalmology. He studied under a professor who gave his name to a type of cataract, yet he severely retarded the progress of cataract surgery throughout Europe. And despite his interest in ocular disease, he was scathing about the idea that eye surgery should exist as a distinct surgical speciality. He was famous in his time and gave his name to several anatomical features, yet was shunned and alone at the time of his death. Who was this contrary doctor and why was his influence on ophthalmology so great? “Scarpa was born into a poor family in the northern Italian town of Motta di Livenzo in 1752. His early education was heavily influenced by his uncle, a priest. And, having become as a result of this tuition an excellent Latinist, he was able to pass the entrance examinations of the University of Padua at just 15 years of age. There he came under the tutelage of the renowned anatomist Giovanni Baptista Morgagni (he of the morgagnic cataract) who became so impressed with Scarpa’s Latin and anatomical skills that he appointed him as his personal assistant and secretary. Scarpa received his medical degree when still only 19 years old from Morgagni himself, only a short time before the great man's death. “With the first of some notable acts of patronage in his favour Morgagni, before his death, had eased the way for Scarpa to obtain the post of Professor of Anatomy and Clinical Surgery at Modena, a mere year later – a post he was to keep for a decade. His star rising, Scarpa published important work on the inner ear in which its membranous labyrinth was elucidated for the first time. But his work on the second tympanic membrane partly mirrored work on the subject by Galvani, who became convinced that he was being plagiarised. Perhaps not coincidentally, Scarpa managed now to obtain funding from the Duke of Modena for a study tour of Europe, thus keeping him away from the worst of the controversy. “The two-year tour of France, Austria and England (where he worked with the famous surgeons John and William Hunter) was a success on its own terms. But probably the most useful outcome of the trip was the friendship he made with Alessandro Brambilla, chief surgeon to Emperor Joseph II of Austria. Soon after his return to Modena he learned that Brambilla had procured an invitation for Scarpa to take up the chair of anatomy at the University of Pavia. The city of Pavia was then under the rule of the Austrian Emperor, and its university one of Italy's oldest and most prestigious. Somehow Scarpa managed to extricate himself from Modena and his previous patron on amicable terms. “Scarpa’s first lecture at Pavia, on November 25 1783, was to prove a watershed in medical education. Instead of a lecture in the classic style, Scarpa gave an anatomical demonstration showing the relationship between structures and organs while paying due attention to the physiology of those structures. The students were required to repeat his exercises in dissection so as to gain knowledge by experience, a standard technique in medical schools today. “Emperor Joseph II’s patronage was important in Pavia becoming the world’s premier centre of anatomical study. Scarpa’s innovative teaching and research were pivotal too and resulted in him being given an additional post after four years there, the chair of clinical surgery. At Scarpa’s suggestion, the emperor decreed that all the bodies of the deceased from the state hospital were to be transferred to the medical school - this at a time when Burke and Hare were still active in the cadaver 'trade' in Britain. Also at Scarpa’s prompting, the medical students were equipped by the emperor with microscopes, instruments and other necessary provisions. These bounties along with new buildings to work in attracted over 2,000 students from throughout Europe to Pavia's medical school, most of whom attended some of Scarpa’s lectures. Thus was his fame and authority ensured, as his students disseminated his name and works across the continent. “One of these works was his Saggio di osservazioni e d'esperienze sulle principali malattie degli occhi (Treatise on Principal Diseases of the Eye), published in 1801. As the title implies, this was not an exhaustive textbook on ocular disease rather, as he explains in his preface, it was an account of ‘the principal affections of the organ, which I have sedulously and repeatedly attended to.’ The root of his interest in eyes was his early association with Morgagni, but he was not an eye specialist as such. Although ophthalmology as a distinct medical speciality did not really exist at that time he abhorred the idea of a surgeon narrowing his expertise to one field. So his preface also states, ‘Professed oculists who have entirely devoted themselves to this department, and from whom great and important improvements might justly have been expected, have only contributed new theories, which, for the most part, been disproved by a minute anatomical investigation of the eye, or have merely furnished histories of cures little less than miraculous.’ “The book was a staggering success. Over the next 36 years it ran to five Italian editions, two each in English and German and one each in Dutch and Spanish. Its popularity was partly due to having a star name as author. But the quality of the illustrations was outstanding too. Scarpa was a gifted artist who produced all his own drawings for the book, as well as supervising their reproduction as engravings. He also controlled the overall appearance of the book by specifying the paper, typeface and bindings to be used. That he was able to do this for all his works speaks again of his skill in raising funds via patrons in the nobility. “Scarpa’s opinions were so influential that his advocacy of traditional ‘couching’ over lens extraction for treatment of cataract held sway for around the next 50 years, as can be seen from textbooks on eye surgery during the first half of the 18th century. It was towards the end of that time that ophthalmology as a separate speciality began to be recognised. “His success as surgeon and author allowed Scarpa to live the good life. He had built for himself a villa outside the city and covered its walls with an impressive collection of paintings. Another fine collection, one of anatomical specimens, was lost during the many battles for the city between Napoleonic France and Austria. Invading Cossack troops emptied the containers of the specimens and drank the preserving spirits. “Scarpa otherwise used the wars to his advantage by expediently aligning his allegiance to the changing political rulers to increase his own power within the university. By 1813 he was Rector and virtual dictator of the medical faculty. But his ruthlessness towards his colleagues came at a price: by 1832 he was friendless and blind. Shunned by his fellow professionals, he died that year during an attack of inflammation of the bladder. “Scarpa was respected for his work but detested as a man. On his funeral day his marble bust was defaced with the lines, ‘Scarpa is dead.,And I should care. He lived like a hog, And died like a dog.’ His assistant later exhumed his body and performed a detailed dissection of it, a fitting postscript to his life, perhaps. It is a final paradox that Scarpa’s hugely influential book really marked the end of an era and that a corpus of modern ophthalmological literature began to appear just after the last edition of the Treatise was published” (Baker). Garrison-Morton 5835; Heirs of Hippocrates 1106; Waller 8543; Norman 1899. Baker, ‘Master of anatomy’ (https://www.opticianonline.net/features/master-of-anatomy).

Large 4to (304 x 215 mm), pp. [iv, engraved portrait frontispiece and title], xi, [1, blank], 278, [1, errata], with 3 engraved plates by E. Anderloni after Scarpa’s drawings. Contemporary stiff marbled wrappers, printed paper label on spine.

Item #5791

Price: $2,500.00