Epytoma in Almagestum Ptolemaei.

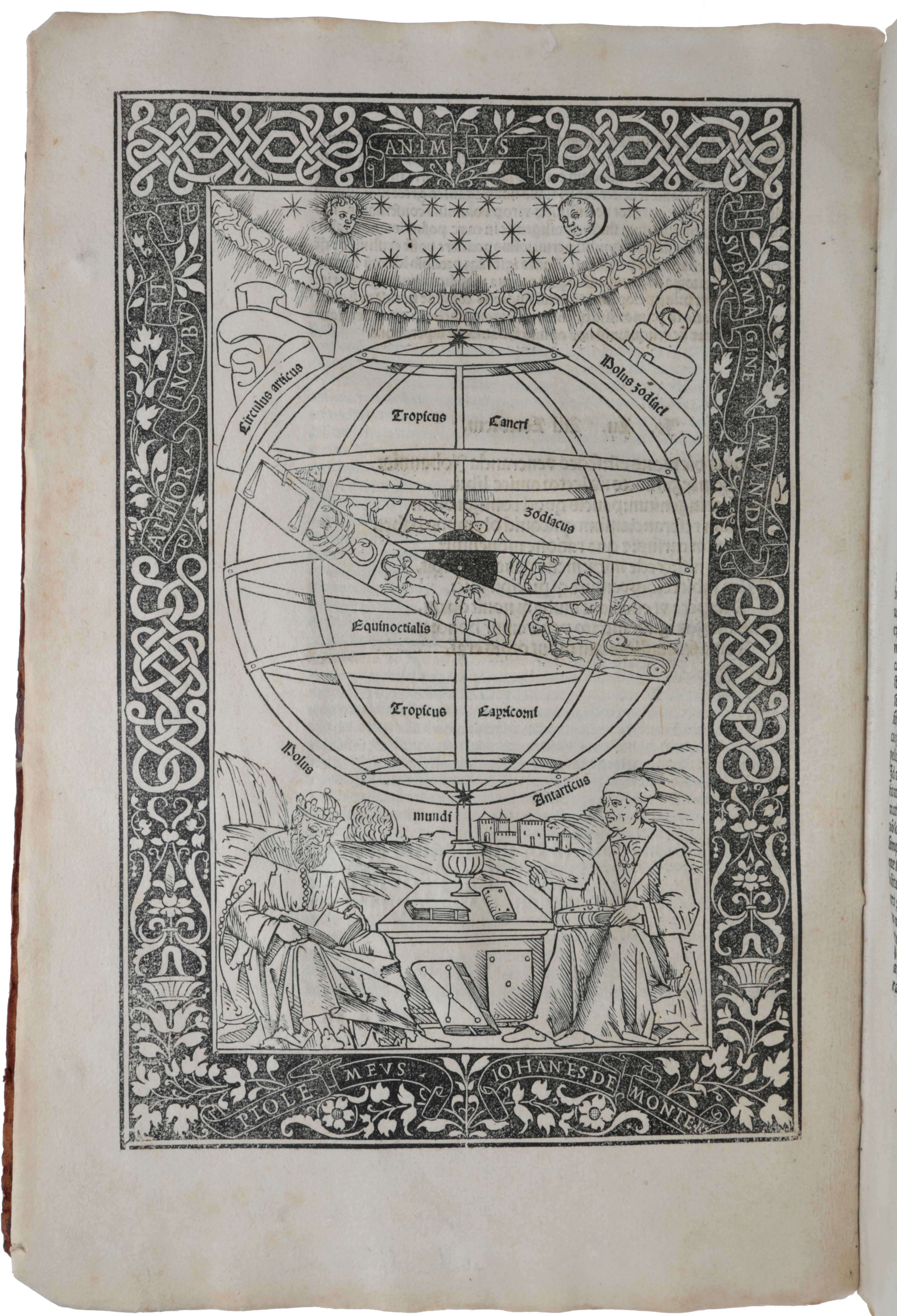

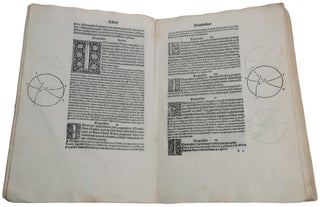

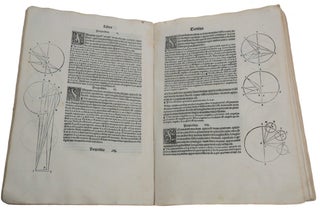

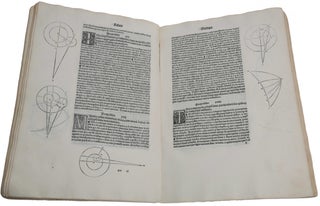

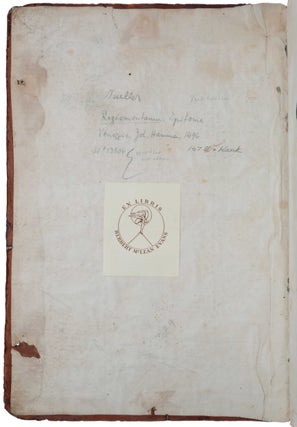

Venice: Johannes Hamman, 31 August 1496. First edition, rare, the Evans-Honeyman-Beltrame copy, of “this celebrated work, the first published matter from the Almagest, [which] was begun by Purbach and completed by Regiomontanus” (Evans). “The importance of this book lies in the fact that it enshrine, within the editor’s commentary, the first appearance in print, in a Latin translation from the Greek, of the monumental compendium of Claudius Ptolemaeus of Alexandria known as the Almagest” (PMM), the foundation of ancient astronomy. “The Almagest of Ptolemy (90-180 AD) had been known since the late 1100s only through a poor Arabic translation until Cardinal Bessarion charged the eminent Georgius Peuerbach with the task of properly editing the text. Only the first four books were completed when Peuerbach died in 1461 and the work was finished by his pupil Regiomontanus. This handsome volume again brought Greek astronomy and the accepted version of the universe before the Western world in Latin, a language all learned men could read. The xylographic portrait of Regiomontanus is considered authentic” (Dibner, Heralds, 1). “The Epitome of the Almagest was a new astronomical treatise. It paved the way for future investigations on the basis of fundamental observations and findings of the past, and his pointing out defects stimulated new research. Both Copernicus and Galileo used it as their textbook” (Zinner, Regiomontanus: his life and work, p. 54). The Epitome is “a model of clarity and includes everything essential to a working understanding of mathematical astronomy and even manages to clarify sections in which Ptolemy omits steps or is somewhat obscure. It has not been superseded even by the excellent modern commentaries on the Almagest, and the mathematical astronomy of the sixteenth century is in places unintelligible without it” (DSB, under Peurbach). “At the end of the fifteenth century, Ptolemy’s achievement remained at the pinnacle of astronomical thought; and by providing easier access to Ptolemy’s complex masterpiece, the Peuerbach-Regiomontanus Epitome contributed to current scientific research rather than to improved understanding of the past. Moreover, the Epitome was no mere compressed translation of the Syntaxis [i.e., the Almagest], to which it added later observations, revised computations, and critical reflections—one of which revealed that Ptolemy’s lunar theory required the apparent diameter of the moon to vary in length much more than it really does. This passage (book V, proposition 22) in the Epitome, which was printed in Venice, attracted the attention of Copernicus, then a student at the University of Bologna. Struck by this error in Ptolemy’s astronomical system, which had prevailed for over 1,300 years, Copernicus went on to lay the foundations of modern astronomy and thus overthrow the Ptolemaic system” (DSB, under Regiomontanus). Copernicus “owned a copy of the Epytoma and had himself been taught by Regiomontanus’s pupil Domenico Maria Novara … Regiomontanus’s treatment of another problem – the so-called second anomaly – may even have led Copernicus to experiment with a heliocentric model” (Rose, The Italian Renaissance of Mathematics, p. 94). Regiomontanus had hoped to publish the Epytoma at his own short-lived Nuremberg press (active 1473-1475), but his premature death at the age of 40 in 1476 delayed its appearance for more than twenty years. Provenance: Convent at ?Montis Fortini (partly erased inscription; later stamp); a few marginal drawings/annotations; Herbert McLean Evans (1882-1971), anatomist, endocrinologist and book collector on the history of science and medicine (bookplate); Robert Honeyman (sale Sotheby's, 11 November 1980, lot 2603); Giancarlo Beltrame (sale, Christie’s 13 July 2016, lot 86). Born in Austria, Georg Peurbach (1423-61) matriculated for the baccalaureate at the University of Vienna in 1446 and received the bachelor’s degree in the Arts Faculty on 2 January 1448. Two years later he probably became a licentiate, and on 28 February 1453 he received the master’s degree and was enrolled in the Arts Faculty. It is unclear with whom, or indeed if, he formally studied astronomy. The last notable astronomer at Vienna, John of Gmunden, had died in 1442, prior to Peurbach’s arrival, but it is possible that he had access to astronomical books and instruments collected by John of Gmunden. During the period 1448–1453, Peurbach traveled through Germany, France, and Italy, at the end of which he appears to have acquired an international reputation. After his return to Vienna, Peurbach became court astrologer to King Ladislaus V of Hungary, the young nephew of Emperor Frederick III. At some later time, Peurbach became court astrologer to the emperor himself, since Regiomontanus refers to him as ‘astronomus caesaris’ in the dedication of the Epitome and cites his service to Frederick in the lecture given at Padua. During this period, Peurbach’s responsibilities at the university were concerned mostly with humanistic rather than astronomical studies. “Regiomontanus (1436-76) enrolled in the University of Vienna on 14 April 1450 as ‘Johannes Molitoris de Künigsperg [Johannes Müller of Königsberg]’. Since the name of his birthplace means ‘King’s Mountain,’ he sometimes Latinized his name as ‘Joannes de Regio monte,’ from which the standard designation Regiomontanus was later derived. He was awarded the bachelor’s degree on 16 January 1452 at the age of fifteen; but because of the regulations of the university, he could not receive the master’s degree until he was twenty-one. On 11 November 1457 he was appointed to the faculty, thereby becoming a colleague of Peuerbach, with whom he had studied astronomy. The two men became fast friends and worked closely together as observers of the heavens. “The course of their lives was deeply affected by the arrival in Vienna on 5 May 1460 of Cardinal Bessarion (1403-72), the papal legate to the Holy Roman Empire” (DSB, under Regiomontanus). “His mission was to intervene in the continuing dispute between Frederick III and his brother Albert VI of Styria and to seek aid in a planned crusade against the Turks for the recapture of Constantinople. In Vienna he met both Peurbach and Regiomontanus. Bessarion was a figure of considerable importance in the transmission of Greek learning to Italy, and his interests were sufficiently diverse to include the exact sciences. He collected a large number of very fine Greek manuscripts that he later left to the city of Venice, where they form the core of the manuscript collection of the Biblioteca Marciana. One of his plans evidently involved a new translation of the Almagest from the Greek to replace Gerard of Cremona’s version from the Arabic and to improve upon the inferior translation from the Greek made by George of Trebizond in 1451. He also desired an abridgment of the Almagest to use as a textbook. Although Peurbach was unfamiliar with Greek, according to Regiomontanus he knew the Almagest almost by heart (quem ille quasi ad litteram memorie tenebat) and so took on the task of preparing the abridgment. Further plans were made for Peurbach and Regiomontanus to accompany Bessarion to Italy and there work with him, using Bessarion’s Greek manuscripts as the basis of the new translation. Peurbach, however, had completed only the first six books of the abridgment when he died, not yet thirty-eight years old. On his deathbed he made Regiomontanus promise to complete the work, which the latter did in Italy during the next year or two. This account is given by Regiomontanus in his preface to the Epitome of the Almagest. The completed work was dedicated to Bessarion by Regiomontanus, probably in 1463, in a very careful and beautifully executed copy (Venice, lat. 328, fols, 1–117). “Peurbach’s early death was a serious loss to the progress of astronomy, if for no other reason than that the collaboration with his even more capable and industrious pupil Regiomontanus promised a greater quantity of valuable work than either could accomplish separately. Of their contemporaries, only Bianchini, who was considerably their senior, possessed a comparable proficiency and originality. The equally early death of Regiomontanus in 1476 left the technical development of mathematical astronomy deprived of substantial improvement until the generation of Tycho Brahe … “According to Regiomontanus, Peurbach was responsible for the first six books of Epitoma Al-magesti Ptolemaei (also known by slight variants of this title), the most important and most advanced Renaissance textbook on astronomy, while books VII-XIII were completed by Regiomontanus after Peurbach’s death. But this account of the division of labor and credit probably requires some modification. The introduction and first six propositions of book I, giving the general arrangement of the universe, are in part translated and in part parapharased from the Greek Almagest and must be the work of Regiomontanus, possibly with assistance from Bessarion … “Aside from the introductory section, books I through VI are closely based upon the so-called Almagesti minoris libri VI, a doubtless unfinished textbook, apparently of the late thirteenth century, that supplements Ptolemy with information and procedures drawn from al-Battānī, Thābit ibn Qurra, Jābir ibn Aflah, az-Zarqāl, and the Toledan Tables. The Almagestum minor divides Ptolemy’s sometimes lengthy chapters into individual propositions showing the proof of a geometrical theorem, the derivation of a parameter, or the carrying out of a procedure, and there are occasional digressions adding the work of post-Ptolemaic writers. The Epitome adopts exactly this arrangement and sometimes follows the Almagestum minor nearly word for word, including all of its supplements to Ptolemy. Evidently Peurbach based the Epitome upon the earlier work; and, with all due respect to Regiomontanus’ account of his teacher’s contribution, one may legitimately ask to what extent the present state of the first six books is really the result of Regiomontanus’ revision of what Peurbach may have left as little more than a close parapharase of the Almagestum minor” (DSB, under Peurbach). “The derivation of planetary paths [in the Almagest] was very awkward, and the necessary mathematical formulas were held to be obsolete, ever since Geber had introduced the Law of Sines for easy solution of spherical triangles, back in the twelfth century. Faced with these defects, Peuerbach took a new tack: he abandoned the restoration of the tables and the lengthy derivation of paths, reproducing the contents of many sections in abbreviated form. In many cases, especially when representing the mathematical relationships between divisions of the heavens, he gave a series of theorems with a well-established foundation; in this way, he introduced his readers to the difficult field of spherical astronomy. “His technique showed itself in the first book: he briefly restated the first six axioms on the place of the earth in the world, following with the theorems in individual sections. He had already discussed the first six sections in his derivation of the table of sines. The 18th section of Book I shows the application of sines, replacing old calculations with arcs and chords … in Book I, Section 17 he describes a quadrant with a scale having two sighting holes, as opposed to Ptolemy’s quadrant, in which a shadow was cast by rods … “Book II (spherical astronomy) is completely altered, but in Book III, he again follows Ptolemy’s way. Nonetheless he does not refrain from pointing out, in the first section, the uncertainty of observing the time of the solstice, saying that it is more suitable to observe the equinoxes. In Section 14 he refers to his own representation of the sun’s entrance into the equinoctial points and neighboring signs and gives a rule for finding the beginnings of the four seasons. However the observations were not communicated. In the following sections he refers to al-Battani’s results again and again. “Book V contains several important sections. In Section 13 he describes the ‘Dreistab’, calling it the Regula Ptolomaei, but unfortunately he omits any statements about its exact arrangement; it is well known that later on, Regiomontanus made it into a fundamental observational instrument. The end of section 22 contains the crucial remark that it is wonderful that the moon does not occasionally appear four times its usual size, as the Ptolemaic theory requires. This reference to a flagrant defect in the prevailing theory must have made an impression on a youthful Copernicus … “[Regiomontanus’s] reworking of Book Vii is worthy of comment. In this book Ptolemy describes the motion of the firmament relative to the zodiac and includes a star catalog. Regiomontanus omits the catalog; otherwise he preserves the reasoning, insofar as he verified the unchangeable positions of the stars relative to each other through his own observations. He then reported on the motion of the firmament as it follows from the observations of Ptolemy and his successors, and refers to the uncertainty of these occasionally contradictory points of view as follows: ‘The inexactness of the instruments may have caused these differences; Nature may have assigned some unknown motion to the stars; it is now and will henceforth be very difficult to determine the amount of this motion due to its small size. For if our predecessors were deceived by their instruments, so necessarily would we, too, for our observations will prove nothing if we do not compare them with those of antiquity. But if we ascribe an unknown motion to the stars, then we must keep the stars firmly under observation and rid the future generations of this tradition.’ “This reference to the necessity of a new determination of stellar motion (the precession) was also significant, in view of the subsequent sections in which Regiomontanus gives instructions for calculating stellar coordinates, if the positions of two stars are known and relative distances between stars are fixed. The two stars’ coordinates are found from the positions of the sun and the moon by means of an armillary sphere, i.e., an instrument composed of several circles. At this point, everything necessary for a new survey of the stars and the production of a new star-catalog was in place. It was now only a matter of beginning with the observations … “The ninth book, on the motion of Venus and Mercury, gave him occasion to make several comments. In Section 1 he mentioned the old assumption that the ratio of the apparent diameters of the sun and Venus was 10:1. Consequently, the sun’s disk equals one hundred of Venus’s, so that a transit of Venus could not be seen … The last four books, concerned with Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, and changes in latitude, did nor prompt him to make any comments … “Now, on which translation of the Almagest was the Epitome based? There are two Latin translations from that time: Gerard of Cremona’s translation of 1175 and George Trebizond of Crete’s translation. The latter translated the original Greek text of the Almagest for Pope Nicholas V and added his own commentary. This version, swiftly written between March and December 1451, was so objectionable that the pope banned Trebizond from Rome. Regiomontanus had obtained both translations while in Vienna. Peuerbach had copied Cremona’s for himself: it was mainly this translation on which Peuerbach and Regiomontanus based their work” (Zinner, pp. 52-54). “At the end of the fifteenth century, Ptolemy’s achievement remained at the pinnacle of astronomical thought; and by providing easier access to Ptolemy’s complex masterpiece, the Peuerbach-Regiomontanus Epitome contributed to current scientific research rather than to improved understanding of the past. Moreover, the Epitome was no mere compressed translation of the Syntaxis, to which it added later observations, revised computations, and critical reflections—one of which revealed that Ptolemy’s lunar theory required the apparent diameter of the moon to vary in length much more than it really does. This passage (book V, proposition 22) in the Epitome, which was printed in Venice, attracted the attention of Copernicus, then a student at the University of Bologna. Struck by this error in Ptolemy’s astronomical system, which had prevailed for over 1,300 years, Copernicus went on to lay the foundations of modern astronomy and thus overthrow the Ptolemaic system” (DSB, under Regiomontanus). In a few copies (for example two out of the thirty-four listed in Goff) there are two inserted leaves containing a letter from the astrologer Giovan Baptista Abioso. It is completely irrelevant, being simply prognostications, and “appears to be a later supplement” (Horblit). HC *13806; BMC V, 427; CIBN R-60; BSB-Ink R-67; Bod-inc R-040; IGI 5326; Klebs 841.1; Essling 895; Sander 6399; Stillwell Science, 103; Dibner, Heralds 1; Evans 14; Grolier/Horblit 89; Norman 1565; Schäfer/Arnim 192; PMM 40; Goff R-111.

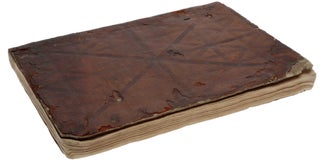

Super-chancery folio (319 x 219mm), ff. [108], with final blank (without the bifolium containing Johannes Baptista Abiosus's letter dated 15 August 1496, inserted in a minority of copies between a1 and 2), Gothic and some Greek types, Xylographic title, full-page woodcut of an armillary sphere with Ptolemy and Regiomontanus studying below, 279 woodcut marginal diagrams (including repeats), woodcut ornamental initials in several sizes, printer’s device (Kristeller 231) (title with early inscription and stamp partly removed and repaired at bottom margin, first quire loosening, faint dampstain at upper corners). Contemporary blind-tooled calf over thin pasteboard, sides diapered with multiple fillets (rebacked, somewhat worn).

Item #5855

Price: $185,000.00