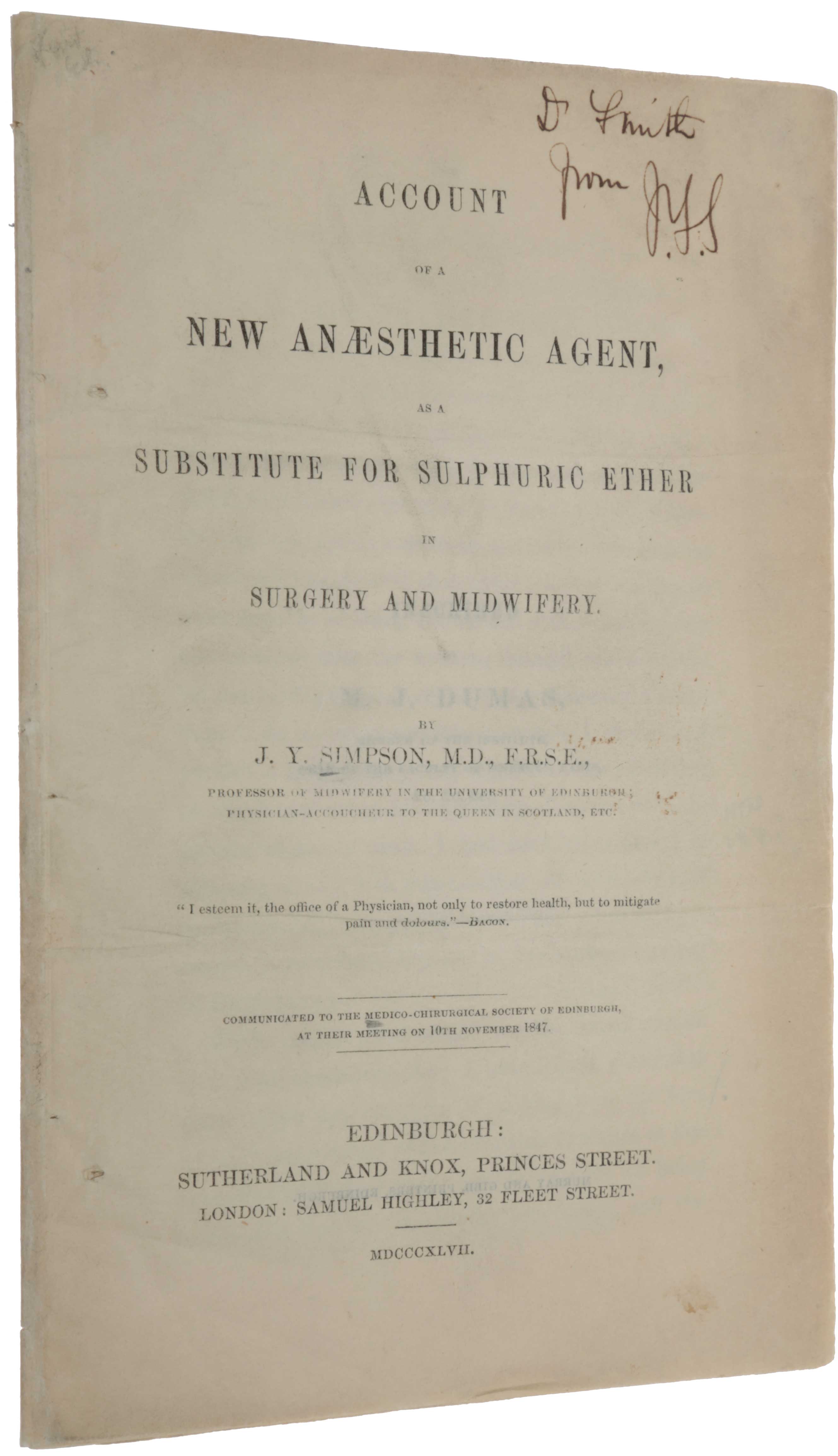

Account of a new anaesthetic agent, as a substitute for sulphuric ether in surgery and midwifery.

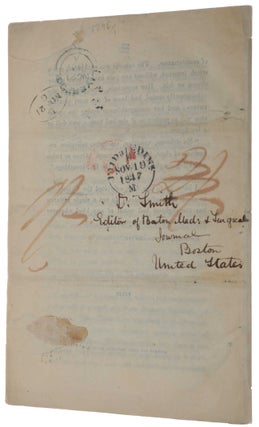

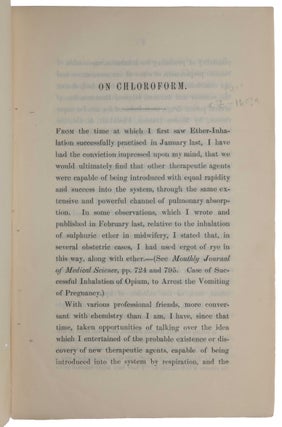

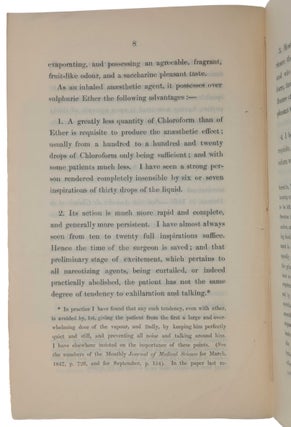

Edinburgh; London: Sutherland and Knox, Princes Street; Samuel Highley, 32 Fleet Street, 1847 [Postscript dated 15 November 1847]. Second edition, extremely rare first issue, inscribed presentation copy, of the first use of chloroform as an anaesthetic. This is the earliest obtainable version of Simpson’s discovery – the first edition, published two or three days earlier, is known in only two copies, both in institutional collections. “While searching for an anaesthetic less irritating than ether, Simpson discovered the advantages of chloroform, and was the first to apply it as a painkiller during labor and childbirth. Simpson first used chloroform in an obstetrical case on 8 November 1847, when he administered it to a woman with a previous history of difficult labor; the baby was born without complications about twenty-five minutes after the first inhalation. Simpson reported his success in an address delivered at the Medico-Chirurgical Society of Edinburgh on 10 November, and immediately afterwards published the address in this pamphlet, with a postscript describing surgical cases. In spite of Simpson’s success with chloroform, he encountered a great deal of opposition from conservative doctors and clergyman who considered labor pains a God-given punishment for Eve’s sins, and he embarked on a long publishing campaign to convert the opposition. His most famous non-scientific argument was that God Himself had been the first anaesthetist when he ‘caused a deep sleep to fall upon Adam before bringing forth Eve from his rib’ (Genesis II:21). Simpson’s efforts were finally accepted by the medical establishment when Queen Victoria chose to take chloroform for the birth of Prince Leopold in 1853” (Norman). “Chloroform and ether have not been used as human anesthetics since the 1950s; in the past few decades synthetic gases with fewer side effects have replaced the older agents. Yet Simpson’s work a century and a half ago legitimized the use of medical interventions to relieve the pain of labor. Millions of women around the world whose labor pains have been eased by various types of anesthesia have benefited from Simpson's ground-breaking efforts” (Science and Its Times: Understanding the Social Significance of Scientific Discovery). ABPC/RBH list no copy of the first edition and only this copy (the Norman copy) of the first issue of the second edition (the second and later issues are notably less rare). Provenance: 1. Presentation copy, inscribed on the title: ‘Dr. Smith/from J.Y.S.’ Simpson apparently mailed the pamphlet to Smith without an envelope, addressing it on the blank verso of the last leaf to: ‘Dr. Smith/Editor of Boston Med: & Surgical/Journal/Boston/United States.’ This page also bears two postmarks, one dated 19 November 1847 at Edinburgh, and the other dated 21 November 1847 at Liverpool. The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, edited by J. V. C. Smith, first mentioned Simpson’s discovery in its issue of 29 December 1847, and acknowledged receipt of Simpson’s pamphlet in its issue of 5 January 1848. 2. Warren G. Atwood. 3. Haskell F. Norman. Until the end of the 18th century, surgeons were unable to offer patients much more than opium, alcohol or a bullet to bite on to deal with the agonizing pain of surgery. Based upon his ‘Researches, Chemical and Philosophical: Chiefly Concerning Nitrous Oxide’ (1799), the English chemist Humphry Davy suggested inhalation of nitrous oxide during surgical operations, but this was not acted upon. In 1813, Davy was joined at the Royal Institution by his assistant Michael Faraday, who studied the inhalation of ether. He published his findings, which included soporific and analgesic effects, in 1818, but again these findings were not followed up, possibly because of the difficulty of quantifying and controlling the effects of ether (one subject had taken over 24 hours to recover full consciousness). The focus of developments now moved to the United States. In 1845, Boston dentists William T.G. Morton and Horace Wells experimented with nitrous oxide, but in an infamous demonstration at Harvard Medical School, the two dentists failed to deaden the pain of a subject having a tooth pulled. Morton persisted, however, and on October 16, 1846, he used sulphuric ether to anaesthetize a man who needed surgery to remove a vascular tumour from his neck; Morton had attended lectures in 1844 by the Harvard chemist Charles Jackson who demonstrated that sulphuric ether could render a person unconscious or even insensate. News of Morton’s discovery did not reach Britain until December 1846 (it was first formally announced in the Lancet in July 1847). Dr. Francis Boott, an expatriate American, learning of Morton’s success through a letter from Boston, arranged for a Miss Lonsdale to have a tooth removed by James Robinson before a group which included Robert Liston. Liston, then London’s leading surgeon, was so impressed that he arranged to perform an amputation under ether on December 21 at University College Hospital, the first public demonstration in Britain. This happened to be the time of the annual visit to London of James ‘Young’ Simpson, Professor of Midwifery in Edinburgh. James Simpson was born in Bathgate, Scotland on 7th June 1811. He qualified in medicine in 1830 at the age of nineteen and went on to specialize in obstetrics. He was appointed Professor of Midwifery in Edinburgh at the age of thirty, an extremely prestigious appointment for one so young. It is rumoured that he added ‘Young’ to his name at this time although there is no conclusive evidence to support this. “In the midst of his now immense daily work he gave all his spare time, often only the midnight hours, to testing upon himself the effect of numerous drugs. With the same courage that had filled Morton he sat down alone, or with Dr. George Keith and Dr. Matthew Duncan, his assistants, to inhale substance after substance, often to the real alarm of [his] household. Appeal was made to scientific chemists to provide drugs hitherto known only as curiosities of the laboratory, and for others that their special knowledge might be able to suggest. The experiments usually took place in the dining room in the quiet of the evening or the dead of night. The enthusiasts sat at the table and inhaled the particular substance under trial from tumblers or saucers; but the summer of 1847 passed away, and the autumn was commenced before he succeeded in finding any substance which at all fulfilled his requirements … “The suggestion to try chloroform first came from a Mr. Waldie, a native of Linlithgowshire, settled in Liverpool as a chemist. It was a ‘curious liquid,’ discovered and described in 1831 by two chemists, Soubeiran and Liebig, simultaneously but independently. In 1835 its chemical composition was first accurately ascertained by Dumas, the famous French chemist. Simpson was apparently not aware that early in 1847 another French chemist, Flourens, had drawn attention to the effect of chloroform upon animals, or he would probably have hastened to use it upon himself experimentally, instead of putting away the first specimen obtained as unlikely; it was heavy and not volatile looking, and less attractive to him than other substances. How it finally came to be tried is best described in the words of Simpson’s colleague and neighbour, Professor Miller, who used to look in every morning at nine o’clock to see how the enthusiasts had fared in the experiments of the previous evening. “Late one evening, it was the 4th of November, 1847, on returning home after a weary day’s labour, Dr. Simpson with his two friends and assistants, Drs. Keith and Duncan, sat down to their somewhat hazardous work in Dr. Simpson’s dining-room. Having inhaled several substances, but without much effect, it occurred to Dr. Simpson to try a ponderous material which he had formerly set aside on a lumber-table, and which on account of its great weight he had hitherto regarded as of no likelihood whatever; that happened to be a small bottle of chloroform. It was searched for and recovered from beneath a heap of waste paper. And with each tumbler newly charged, the inhalers resumed their vocation. Immediately an unwonted hilarity seized the party—they became bright-eyed, very happy, and very loquacious—expatiating on the delicious aroma of the new fluid. The conversation was of unusual intelligence, and quite charmed the listeners—some ladies of the family and a naval officer, brother-in-law of Dr. Simpson. But suddenly there was a talk of sounds being heard like those of a cotton mill louder and louder; a moment more and then all was quiet—and then crash! On awakening Dr. Simpson’s first perception was mental—‘This is far stronger and better than ether,’ said he to himself. His second was to note that he was prostrate on the floor, and that among the friends about him there was both confusion and alarm. Hearing a noise he turned round and saw Dr. Duncan beneath a chair—his jaw dropped, his eyes staring, his head bent half under him; quite unconscious, and snoring in a most determined and alarming manner. More noise still and much motion. And then his eyes overtook Dr. Keith’s feet and legs making valorous attempts to overturn the supper table, or more probably to annihilate everything that was on it. By and by Dr. Simpson having regained his seat, Dr. Duncan having finished his uncomfortable and unrefreshing slumber, and Dr. Keith having come to an arrangement with the table and its contents, the sederunt was resumed. Each expressed himself delighted with this new agent, and its inhalation was repeated many times that night—one of the ladies gallantly taking her place and turn at the table—until the supply of chloroform was fairly exhausted.’ “The lady was Miss Petrie, a niece of Mrs. Simpson’s; she folded her arms across her breast as she inhaled the vapour, and fell asleep crying, “I’m an angel! Oh, I’m an angel”! The party sat discussing their sensations, and the merits of the substance long after it was finished; they were unanimous in considering that at last something had been found to surpass ether. “The following morning a manufacturing chemist was pressed into service, and had to burn the midnight oil to meet Simpson’s demand for the new substance. So great was Simpson’s midwifery practice that he was able to make immediate trial of chloroform, and on November 10th he read a paper to the Medico-Chirurgical Society, describing the nature of his agent, and narrating cases in which he had already successfully used it. ‘I have never had the pleasure,’ he said, ‘of watching over a series of better and more rapid recoveries; nor once witnessed any disagreeable results follow to either mother or child; whilst I have now seen an immense amount of maternal pain and agony saved by its employment. And I most conscientiously believe that the proud mission of the physician is distinctly twofold—namely to alleviate human suffering as well as preserve human life.’ In a postscript to the same paper he states on November 15th that he had already administered chloroform to about fifty individuals without the slightest bad result, and gives an account of the first surgical cases in which he gave the agent to patients of his friends, Professor Miller and Dr. Duncan, in the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary. ‘A great collection,’ he says, ‘of professional gentlemen and students witnessed the results, and amongst them Professor Dumas, of Paris, the chemist who first ascertained and established the chemical composition of chloroform. He happened to be passing through Edinburgh, and was in no small degree rejoiced to witness the wonderful physiological effects of a substance with whose chemical history his own name was so intimately connected’ … Professor Simpson firmly believed that he possessed now in chloroform an anaesthetic agent ‘more portable, more manageable and powerful, more agreeable to inhale, and less exciting’ than ether, and one giving him ‘greater control and command over the superinduction of the anaesthetic state’” (Laing-Gordon, pp. 109-111). “After Simpson began using chloroform as a safer and more effective anesthetic than ether during the late 1840s, many criticized its use. Individuals objected to the use of chloroform in obstetrics for medical, moral, and religious reasons. Medically, from 1848 onwards, physicians reported numerous accounts of healthy patients dying under the use of chloroform and thus they proclaimed it unsafe. Simpson rebutted that improper administration of chloroform was to blame, not the drug itself. Other individuals protested the use of chloroform in midwifery because they saw the pains associated with labor as beneficial to birthing. Simpson countered by demonstrating that diminishing pain hastened the birth-giving process and led to healthier recoveries. Religiously, other individuals referenced the book of Genesis and Eve’s original sin as justification for the pain women experience during labor and childbirth. According to Gordon, Simpson was a devout man himself, and he gave an analysis of the original Hebrew text to refute that argument. Simpson noted that the Hebrew word for ‘sorrow,’ referring to women’s suffering during childbirth, was translated as the same meaning for two different Hebrew words. One of those words was used to describe the literal labor women exert and the other to describe the associated pain. Therefore, Simpson demonstrated that the religious argument against utilizing pain relief during labor was based on the word for pain, an incorrect interpretation of the religious text” (embryo.asu.edu/pages/james-young-simpson-1811-1870). “Simpson was showered with honours. In 1841 he was elected president of the Edinburgh Obstetric Society at the age of 30, an office he held for the next 17 years. In 1847 he was appointed physician to Queen Victoria in Scotland and three years later was invited to become a member of the staff of the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary, a rare honour for an obstetrician at that time. He was awarded the Order of St Olaf by the King of Sweden, the Monthyon prize of the French Academy of Medicine, and honorary doctorates by Oxford and Dublin. Academies and medical societies from all over the world honoured him. In 1866 he was created a baronet, the first received by a doctor practicing in Scotland, and in 1869 he was granted the Freedom of the City of Edinburgh. “In 1870 Simpson started to suffer from angina and shortness of breath. He made his will, gathered his family around him, and on 6 May 1870 died peacefully in his home, 52 Queen Street. Two thousand mourners followed the cortege to Warriston Cemetery where he was buried, while 50 000 citizens lined the route. His wife, Jessie Grundlay, whom he had married in 1839, died a few weeks later. A statue was erected to Simpson in Princes Street and the Simpson Memorial Pavilion was built with subscriptions raised by his friends. The family had declined an offer for him to be buried in Westminster Abbey. Instead a bust of him was raised there in St Andrew’s chapel with the words: ‘To whose genius and benevolence the world owes the blessings derived from the use of chloroform for the relief of suffering’” (Dunn). “Fulton and Stanton cite two ‘issues’ of this pamphlet, but these should more properly be described as editions, as the text of the second has been reset. The first edition bears a postscript dated November 12, 1847 and was apparently issued almost immediately after that because the second edition appeared with a postscript dated only three days later. The title of the first edition reads: ‘Notice of a new anaesthetic agent …,’ the imprint reads: ‘Edinburgh: Sutherland and Knox, Princes Street,’ and the postscript begins on page 17. In the second edition the title reads: ‘Account of a new anaesthetic agent …,’ the imprint reads: ‘Edinburgh: Sutherland and Knox, Princes Street; London: Samuel Highley, 32 Fleet Street,’ and the postscript, which begins on page 18, is dated 15 November 1847. The postscript in the second edition has an additional paragraph at the end: ‘I have, up to this date, exhibited the Chloroform to about fifty individuals. In not a single instance has the slightest bad result of any kind whatever occurred from its employment.’ Because the Norman copy [offered here] bears a postmark dated November 19, we know that the pamphlet was in Simpson’s hands by that date. Fulton and Stanton apparently never saw the first edition and incorrectly describe the first ‘issue’ as lacking the postscript altogether. Both editions are extremely rare” (Norman). Indeed, “There are two copies of the version of November 12 [the first edition] known to exist in libraries. One is in the Osler Library at McGill University, Montreal; the other is in the Gordon Craig Library of the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons in Melbourne” (Cranefield, pp. 904-905). Cranefield lists (pp. 905-906) the textual differences between the first and second editions. There is a second issue of the second edition which appears to be identical to the first issue except for ‘Third Thousand’ being added to the title page; there is also a third issue dated 1848 with ‘Fourth Thousand’ on the title. There were numerous later reprints in both England and the United States. There were three contemporary journal synopses: ‘On a new anaesthetic agent, more efficient than sulphuric ether,’ Lancet 21, pp. 549-550 [issue dated November 20, 1847] – this is the version cited by Garrison-Morton; ‘Discovery of a new anaesthetic agent, more efficient than sulphuric ether,’ London Medical Gazette, n.s. 5, pp. 934-937 [issue dated November 26, 1847]; ‘Anaesthetic and other therapeutical properties of the inhalation of chloroform,’ Monthly Journal of Medical Science, n.s. 8, pp. 415-417 [issue dated December, 1847]. The events around the publication of these pamphlets are a testament to Simpson’s enormous energy. “It thus appears that in the period from November 4 to November 25 Simpson found the time and had the energy to discover the usefulness of chloroform as an anesthetic agent, give a lecture on that subject to The Medico-Chirurgical Society of Edinburgh, write, expand and revise a pamphlet, see both versions of the pamphlet through the press, send copies of each version of the pamphlet to his friends and colleagues; send three similar but by no means identical manuscripts to Lancet, the London Medical Gazette and the Monthly Journal of the Medical Science and to administer chloroform to ‘above eighty individuals’” (ibid. p. 906). Fulton & Stanton, VI.I; Garrison & Morton, 5657 (citing the synopsis in The Lancet, Vol. 2, pp. 459-550, published about a week after the pamphlets); Lilly Library, Notable Medical Books, p. 201; Norman 1945 (this copy); Osler 1480; Parkinson, Breakthroughs, 1847; cf. Heirs of Hippocrates 1764 (New York 1848 reprint). Cranefield, ‘J. Y. Simpson’s early articles on chloroform,’ Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 62 (1986), pp. 903-909. Dunn, ‘Sir James Young Simpson (1811–1870) and obstetric anaesthesia,’ Archives of Disease in Childhood - Fetal and Neonatal Edition 86 (2002), pp. F207-F209. Laing Gordon, Sir James Young Simpson and Chloroform, 1897.

Simpson was quick to recognize the significance of ether anaesthesia. He had always been concerned with the issue of surgical pain and began experimenting with potential solutions. On 19 January 1847, Simpson introduced ether anaesthesia into obstetrics. He initially used ether for pain relief when surgically intervening during childbirth, but eventually employed it for normal labour as well. After some time using ether as an anaesthetic during 1847, Simpson found the drug to be problematic. It was slow to stimulate pain relief and sometimes irritated the patient’s lungs. Simpson began to experiment with several other chemicals, including acetone, nitric ether, benzine, iodoformvapour, chloride of hydrocarbon, aldehyde and bisulphuret of carbon.

8vo (213 x 135mm), ff. [12] (title-leaf and last four leaves detached, upper blank corner of final leaf torn away, slight soiling to title and last leaf). Unbound as issued (formerly stab-stitched, trace of thread remaining); folding fitted chemise and morocco-backed slipcase.

Item #5874

Price: $65,000.00