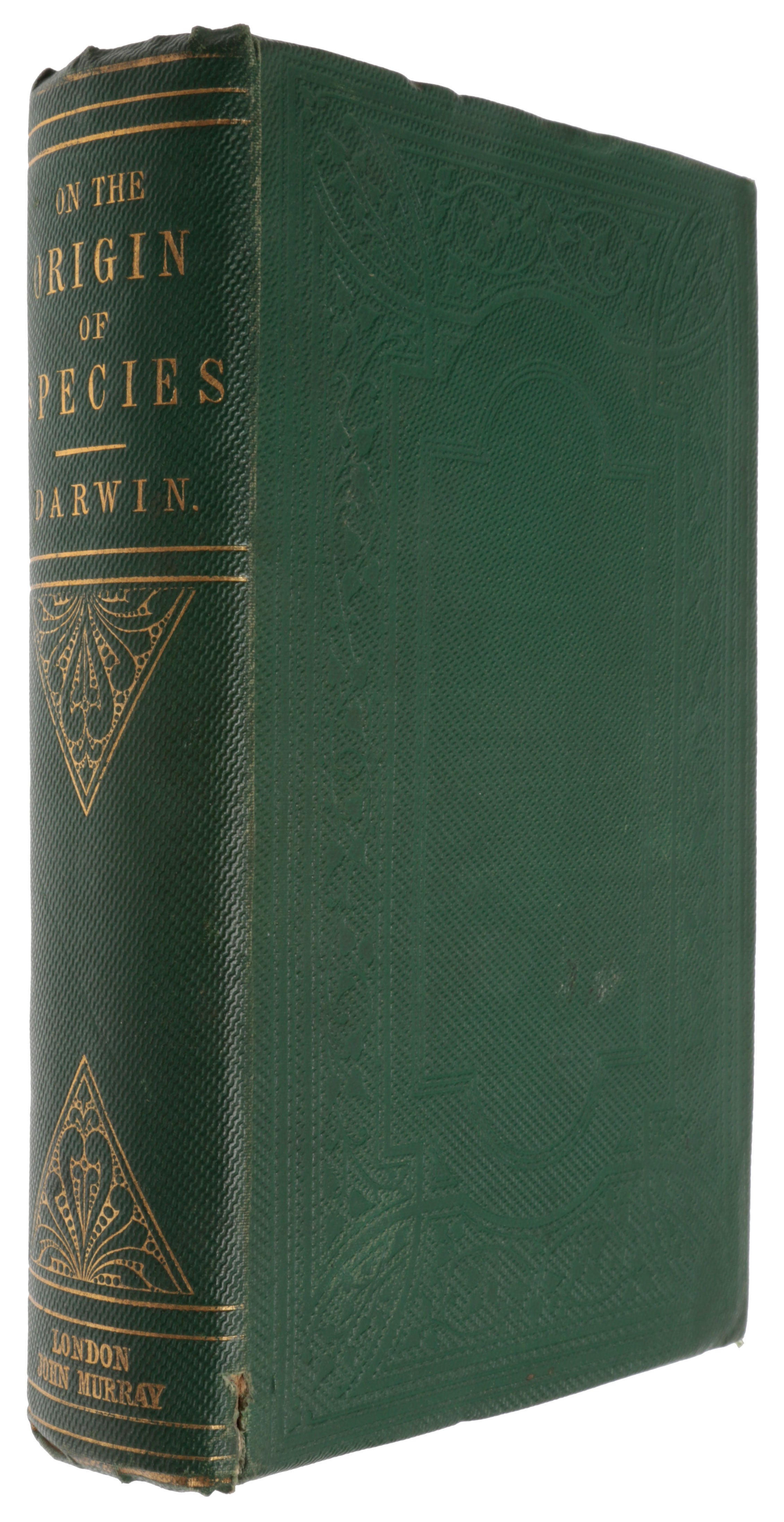

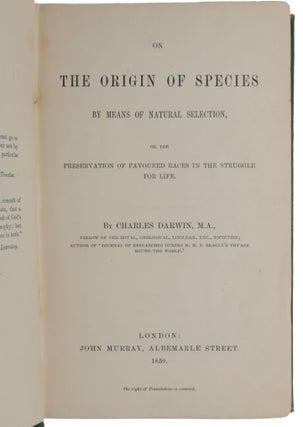

On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life.

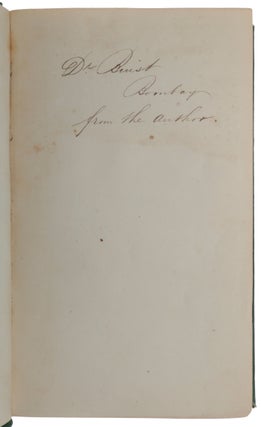

London: John Murray, 1859. First edition, presentation copy, of “the most influential scientific work of the nineteenth century” (Horblit), “the most important biological work ever written” (Freeman), and “a turning point, not only in the history of science, but in the history of ideas in general” (DSB). “Darwin not only drew an entirely new picture of the workings of organic nature; he revolutionized our methods of thinking and our outlook on the natural order of things. The recognition that constant change is the order of the universe had been finally established and a vast step forward in the uniformity of nature had been taken” (PMM). Bern Dibner’s Heralds of Science describes On the Origin of Species as “the most important single work in science.” When the first edition was published on 24 November 1859, in a print run of 1,250 copies, it created an immediate sensation. Fifty-eight were distributed by Murray for review, promotion, and presentation, and Darwin reported that the balance was sold out on the first day of publication. Five further editions, each variously corrected and revised, appeared in Darwin’s lifetime, as did eleven translations. The Origin was actually an ‘abstract’ of a larger work, tentatively titled Natural Selection, that Darwin never completed, although he salvaged much of the first part of the manuscript for The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication, published in 1868. The presentation copies likely number less than 30, all having secretarial inscriptions and were sent by the publisher at Darwin's request. “There are no known author's presentation copies of the first edition inscribed in Darwin's hand” (Norman). Provenance: Inscribed in a secretarial hand ‘Dr. Buist / Bombay / from the author’ (as described in the list of presentation copies of the Origin in Vol 8, Appendix III, p 556 and further note on p 559). Dr. George Buist (1805-60) was a founding member of the Literary and Philosophical Society of St. Andres, of which Darwin was an ‘Honorable Member’. After taking degrees at St. Andrews and the University of Edinburgh, Buist left Scotland for a journalistic posting in India, where his scientific interests led him to serve as Secretary to the Bombay Geographical Society, the same role Darwin played for the London Geographical Society. Both men were fellows of the Royal Society. “England became quieter and more prosperous in the 1850s, and by mid-decade the professionals were taking over, instituting exams and establishing a meritocracy. The changing social composition of science—typified by the rise of the freethinking biologist Thomas Henry Huxley—promised a better reception for Darwin. Huxley, the philosopher Herbert Spencer, and other outsiders were opting for a secular nature in the rationalist Westminster Review and deriding the influence of “parsondom.” Darwin had himself lost the last shreds of his belief in Christianity with the tragic death of his oldest daughter, Annie, from typhoid in 1851 … “After speaking to Huxley and Hooker at Downe in April 1856, Darwin began writing a triple-volume book, tentatively called Natural Selection, which was designed to crush the opposition with a welter of facts. Darwin now had immense scientific and social authority, and his place in the parish was assured when he was sworn in as a justice of the peace in 1857. Encouraged by Lyell, Darwin continued writing through the birth of his 10th and last child, Charles Waring Darwin (born in 1856, when Emma was 48), who was developmentally disabled. Whereas in the 1830s Darwin had thought that species remained perfectly adapted until the environment changed, he now believed that every new variation was imperfect, and that perpetual struggle was the rule. He also explained the evolution of sterile worker bees in 1857. Those could not be selected because they did not breed, so he opted for “family” selection (kin selection, as it is known today): the whole colony benefited from their retention. “Darwin had finished a quarter of a million words by June 18, 1858. That day he received a letter from Alfred Russel Wallace, an English socialist and specimen collector working in the Malay Archipelago, sketching a similar-looking theory. Darwin, fearing loss of priority, accepted Lyell’s and Hooker’s solution: they read joint extracts from Darwin’s and Wallace’s works at the Linnean Society on July 1, 1858. Darwin was away, sick, grieving for his tiny son who had died from scarlet fever, and thus he missed the first public presentation of the theory of natural selection. It was an absenteeism that would mark his later years. “Darwin hastily began an “abstract” of Natural Selection, which grew into a more-accessible book, On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life. Suffering from a terrible bout of nausea, Darwin, now 50, was secreted away at a spa on the desolate Yorkshire moors when the book was sold to the trade on November 22, 1859. He still feared the worst and sent copies to the experts with self-effacing letters (“how you will long to crucify me alive”). It was like “living in Hell,” he said about those months. “The book did distress his Cambridge patrons, but they were marginal to science now. However, radical Dissenters were sympathetic, as were the rising London biologists and geologists, even if few actually adopted Darwin’s cost-benefit approach to nature. The newspapers drew the one conclusion that Darwin had specifically avoided: that humans had evolved from apes, and that Darwin was denying mankind’s immortality. A sensitive “Darwin, making no personal appearances, let Huxley, by now a good friend, manage that part of the debate. The pugnacious Huxley, who loved public argument as much as Darwin loathed it, had his own reasons for taking up the cause, and did so with enthusiasm. He wrote three reviews of Origin of Species, defended human evolution at the Oxford meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in 1860 (when Bishop Samuel Wilberforce jokingly asked whether the apes were on Huxley’s grandmother’s or grandfather’s side), and published his own book on human evolution, Evidence as to Man’s Place in Nature (1863). What Huxley championed was Darwin’s evolutionary naturalism, his non-miraculous assumptions, which pushed biological science into previously taboo areas and increased the power of Huxley’s professionals. And it was they who gained the Royal Society’s Copley Medal for Darwin in 1864” (Britannica). “Chapter I covers animal husbandry and plant breeding, going back to ancient Egypt. Darwin discusses contemporary opinions on the origins of different breeds under cultivation to argue that many have been produced from common ancestors by selective breeding. As an illustration of artificial selection, he describes fancy pigeon breeding, noting that ‘[t]he diversity of the breeds is something astonishing’, yet all were descended from one species of rock pigeon. Darwin saw two distinct kinds of variation: (1) rare abrupt changes he called ‘sports’ or ‘monstrosities’ (example: Ancon sheep with short legs), and (2) ubiquitous small differences (example: slightly shorter or longer bill of pigeons). Both types of hereditary changes can be used by breeders. However, for Darwin the small changes were most important in evolution. “In Chapter II, Darwin specifies that the distinction between species and varieties is arbitrary, with experts disagreeing and changing their decisions when new forms were found. He concludes that ‘a well-marked variety may be justly called an incipient species" and that "species are only strongly marked and permanent varieties’. He argues for the ubiquity of variation in nature … Darwin and Wallace made variation among individuals of the same species central to understanding the natural world. “In Chapter III, Darwin asks how varieties ‘which I have called incipient species’ become distinct species, and in answer introduces the key concept he calls ‘natural selection’ ... Owing to this struggle for life, any variation, however slight and from whatever cause proceeding, if it be in any degree profitable to an individual of any species, in its infinitely complex relations to other organic beings and to external nature, will tend to the preservation of that individual, and will generally be inherited by its offspring ... I have called this principle, by which each slight variation, if useful, is preserved, by the term of Natural Selection, in order to mark its relation to man’s power of selection’ … “Chapter IV details natural selection under the ‘infinitely complex and close-fitting ... mutual relations of all organic beings to each other and to their physical conditions of life’. Darwin takes as an example a country where a change in conditions led to extinction of some species, immigration of others and, where suitable variations occurred, descendants of some species became adapted to new conditions. He remarks that the artificial selection practised by animal breeders frequently produced sharp divergence in character between breeds, and suggests that natural selection might do the same, saying: ‘But how, it may be asked, can any analogous principle apply in nature? I believe it can and does apply most efficiently, from the simple circumstance that the more diversified the descendants from any one species become in structure, constitution, and habits, by so much will they be better enabled to seize on many and widely diversified places in the polity of nature, and so be enabled to increase in numbers’ ... Darwin proposes sexual selection, driven by competition between males for mates, to explain sexually dimorphic features such as lion manes, deer antlers, peacock tails, bird songs, and the bright plumage of some male birds ... Using a tree diagram and calculations, he indicates the ‘divergence of character’ from original species into new species and genera. He describes branches falling off as extinction occurred, while new branches formed in ‘the great Tree of life ... with its ever branching and beautiful ramifications’ ... “Chapter V discusses what he called the effects of use and disuse; he wrote that he thought ‘there can be little doubt that use in our domestic animals strengthens and enlarges certain parts, and disuse diminishes them; and that such modifications are inherited’, and that this also applied in nature. Darwin stated that some changes that were commonly attributed to use and disuse, such as the loss of functional wings in some island dwelling insects, might be produced by natural selection ... “Chapter VI begins by saying the next three chapters will address possible objections to the theory, the first being that often no intermediate forms between closely related species are found, though the theory implies such forms must have existed. As Darwin noted, ‘Firstly, why, if species have descended from other species by insensibly fine gradations, do we not everywhere see innumerable transitional forms? Why is not all nature in confusion, instead of the species being, as we see them, well defined?’ Darwin attributed this to the competition between different forms, combined with the small number of individuals of intermediate forms, often leading to extinction of such forms … Another difficulty, related to the first one, is the absence or rarity of transitional varieties in time. Darwin commented that by the theory of natural selection ‘innumerable transitional forms must have existed,’ and wondered ‘why do we not find them embedded in countless numbers in the crust of the earth?’ The chapter then deals with whether natural selection could produce complex specialised structures, and the behaviours to use them, when it would be difficult to imagine how intermediate forms could be functional. Darwin said: ‘Secondly, is it possible that an animal having, for instance, the structure and habits of a bat, could have been formed by the modification of some animal with wholly different habits? Can we believe that natural selection could produce, on the one hand, organs of trifling importance, such as the tail of a giraffe, which serves as a fly-flapper, and, on the other hand, organs of such wonderful structure, as the eye, of which we hardly as yet fully understand the inimitable perfection?’ His answer was that in many cases animals exist with intermediate structures that are functional … Darwin concludes: ‘If it could be demonstrated that any complex organ existed, which could not possibly have been formed by numerous, successive, slight modifications, my theory would absolutely break down. But I can find out no such case’... “Chapter VII addresses the evolution of instincts. His examples included two he had investigated experimentally: slave-making ants and the construction of hexagonal cells by honey bees. Darwin noted that some species of slave-making ants were more dependent on slaves than others, and he observed that many ant species will collect and store the pupae of other species as food. He thought it reasonable that species with an extreme dependency on slave workers had evolved in incremental steps. He suggested that bees that make hexagonal cells evolved in steps from bees that made round cells, under pressure from natural selection to economise wax … “Chapter VIII addresses the idea that species had special characteristics that prevented hybrids from being fertile in order to preserve separately created species. Darwin said that, far from being constant, the difficulty in producing hybrids of related species, and the viability and fertility of the hybrids, varied greatly, especially among plants. Sometimes what were widely considered to be separate species produced fertile hybrid offspring freely, and in other cases what were considered to be mere varieties of the same species could only be crossed with difficulty. Darwin concluded: ‘Finally, then, the facts briefly given in this chapter do not seem to me opposed to, but even rather to support the view, that there is no fundamental distinction between species and varieties’ ... “Chapter IX deals with the fact that the geological record appears to show forms of life suddenly arising, without the innumerable transitional fossils expected from gradual changes. Darwin borrowed Charles Lyell’s argument in Principles of Geology that the record is extremely imperfect as fossilisation is a very rare occurrence, spread over vast periods of time; since few areas had been geologically explored, there could only be fragmentary knowledge of geological formations, and fossil collections were very poor. Evolved local varieties which migrated into a wider area would seem to be the sudden appearance of a new species ... “Chapter X examines whether patterns in the fossil record are better explained by common descent and branching evolution through natural selection, than by the individual creation of fixed species. Darwin expected species to change slowly, but not at the same rate – some organisms such as Lingula were unchanged since the earliest fossils. The pace of natural selection would depend on variability and change in the environment. This distanced his theory from Lamarckian laws of inevitable progress ... “Chapter XI deals with evidence from biogeography, starting with the observation that differences in flora and fauna from separate regions cannot be explained by environmental differences alone; South America, Africa, and Australia all have regions with similar climates at similar latitudes, but those regions have very different plants and animals. The species found in one area of a continent are more closely allied with species found in other regions of that same continent than to species found on other continents ... Chapter XII continues the discussion of biogeography … The summary of both chapters says: ‘I think all the grand leading facts of geographical distribution are explicable on the theory of migration (generally of the more dominant forms of life), together with subsequent modification and the multiplication of new forms. We can thus understand the high importance of barriers, whether of land or water, which separate our several zoological and botanical provinces. We can thus understand the localisation of sub-genera, genera, and families; and how it is that under different latitudes, for instance in South America, the inhabitants of the plains and mountains, of the forests, marshes, and deserts, are in so mysterious a manner linked together by affinity, and are likewise linked to the extinct beings which formerly inhabited the same continent ... On these same principles, we can understand, as I have endeavoured to show, why oceanic islands should have few inhabitants, but of these a great number should be endemic or peculiar’. “Chapter XIII starts by observing that classification depends on species being grouped together in a Taxonomy, a multilevel system of groups and sub groups based on varying degrees of resemblance. After discussing classification issues, Darwin concludes: ‘All the foregoing rules and aids and difficulties in classification are explained, if I do not greatly deceive myself, on the view that the natural system is founded on descent with modification; that the characters which naturalists consider as showing true affinity between any two or more species, are those which have been inherited from a common parent, and, in so far, all true classification is genealogical; that community of descent is the hidden bond which naturalists have been unconsciously seeking.’ Darwin discusses morphology, including the importance of homologous structures. He says, ‘What can be more curious than that the hand of a man, formed for grasping, that of a mole for digging, the leg of the horse, the paddle of the porpoise, and the wing of the bat, should all be constructed on the same pattern, and should include the same bones, in the same relative positions?’ This made no sense under doctrines of independent creation of species, as even Richard Owen had admitted, but the ‘explanation is manifest on the theory of the natural selection of successive slight modifications’ … “The final chapter ‘Recapitulation and Conclusion’ reviews points from earlier chapters, and Darwin concludes by hoping that his theory might produce revolutionary changes in many fields of natural history. He suggests that psychology will be put on a new foundation and implies the relevance of his theory to the first appearance of humanity with the sentence that ‘Light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history.’ Darwin ends with a passage that became well known and much quoted: ‘It is interesting to contemplate an entangled bank, clothed with many plants of many kinds, with birds singing on the bushes, with various insects flitting about, and with worms crawling through the damp earth, and to reflect that these elaborately constructed forms, so different from each other, and dependent on each other in so complex a manner, have all been produced by laws acting around us ... Thus, from the war of nature, from famine and death, the most exalted object which we are capable of conceiving, namely, the production of the higher animals, directly follows. There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved’” (Wikipedia, accessed 14 May 2018). Dibner Heralds of Science 199; Heirs of Hippocrates 1724; Freeman 373; Garrison-Morton 220; Grolier Science 23b; Norman 593; PMM 344b; Sparrow Milestones 49; Waller 10786.

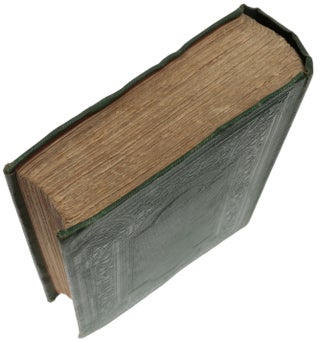

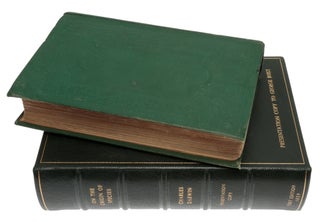

8vo in 12s (201 x 125 mm), pp. ix, [i], 502, [32, publisher's catalogue dated June 1859], with one folding lithographed table. Original publisher’s green cloth, sides stamped in blind, spine in gilt, by Edmonds and Remnants with their ticket on the lower pastedown (rear hinge starting, front hinge sound, though with some splitting to paper over hinge, short tear to cloth at bottom of upper joint, else a very bright copy with no fraying to spine ends or noticeable dulling to cloth, only faint rubbing to gilt rules on spine).

Item #5894

Price: $950,000.00